3 Simple Keys for Using Low Carb, High Carb & Intermittent Fasting for Optimum Metabolism with Dr. Mike T. Nelson

Opinions regarding carb intake vary widely. Fortunately, Dr. Mike T. Nelson draws upon not only his research background, but also his experience in advising clients, to provide us with simple recommendations that can allow you to improve your metabolism by adjusting your carb intake and utilizing intermittent fasting.

Episode Intro

Dr. Michael Ruscio, DC: Hey, everyone, welcome to Dr. Ruscio Radio, this is Dr. Ruscio. Today, I’m here with Dr. Mike T. Nelson, one of the guys I respect the most in the field of exercise, fitness, amongst other things, but really has a very well-researched, very pragmatic, and objective look at whatever he looks into. And the more I get to know Mike, the more I like him.

So Mike, you have some pretty lofty descriptions to live up to today on the podcast.

Dr. Mike Nelson: Yeah, thank you. Hopefully, I make it. We’ll see.

[Continue reading below]

Dr. R’s Fast Facts Summary

Big picture take away…

- If you are having a hard time metabolizing a certain food, removing it or lowering intake is probably going to be beneficial.

- There is no universal prescriptive diet/protocol for a “healthy” individual. Stay in tune with your body and how you feel when trying new things.

Metabolic flexibility:

- How well you use carbohydrates

- How well you use fat

- How well you transition back and forth

Heterogeneity of insulin sensitivity, meaning some people process carbs better than others.

- Some sub-analysis suggest that people who are more prone to insulin resistance may only do well on a lower carb diet whereas people who tend to have good or robust ability to process insulin may be able to improve on any type of diet.

Does health increase metabolic flexibility?

- Some studies and clinical practice suggest that when someone increases their health, their metabolic flexibility improves.

- Hypoglycemia – many people suffer fewer bouts of hypoglycemic episodes as their health improves

- Test the boundaries as your health improves vs sticking with a rigid diet and never changing for fear of hypoglycemia

Gain range can be altered if you eat the same all the time:

- One study showed that in healthy individuals that became reliant on using blood glucose – the gain of the system was altered meaning they couldn’t handle low deviation at all. Blood glucose dropped 10-12 points. Subjects experienced massive hypoglycemic symptoms but the number didn’t seem to reflect it.

Evolution of macros

- Start out with lower carb intake – slight restriction of carbs. This naturally eliminates foods that tend to give people problems like FODMAPS and grains.

- Then if you feel good, evolve into a broader diet and try macro-cycling

Who should try macro cycling?

- Qualify yourself:

- Those who can do 19-ish hour fast

- Those who don’t feel they are under a lot of stress

- Oral glucose tolerance test (80 grams of glucose all at once them measure your response)

- Added benefit – body composition could improve

Who shouldn’t try macro cycling?

- People who are very stressed or fatigued – having smaller amounts of carbs and more frequent meals tends to help.

- Those who feel very sensitive to high carb or high fat intake

How to integrate macro cycling – 3 keys

No seasonal variation recommended

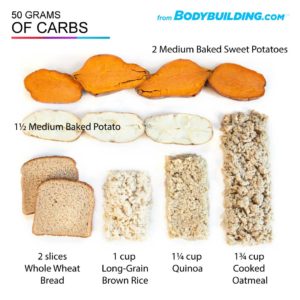

- Training days (3 days per week) eat higher carb (200g/day for men roughly)

- Other days, 12-14 hour overnight fast then perform lower cardio in a.m. – fasted. Eat lower carb on these days (100-120g/day – but not less).

- Protein .7 grams per lb of body weight

- Fat 50-70 grams/day minimum

Fasting vs. Ketogenic diet

- If you are moderately healthy and want to work on body comp and overall health and longevity, fasting is a good way to go.

- A longer fast once a week or a longer overnight fast can be very beneficial and is easier than going in and out of ketosis.

To learn more about Mike T. Nelson or to sign up for his newsletter visit his website.

- Get help using this information to become healthier.

- Get your personalized plan for optimizing your gut health with my new book.

- Healthcare providers looking to sharpen their clinical skills, check out the Future of Functional Medicine Review Clinical Newsletter.

Download Episode (Right click on link and ‘Save As’)

DrMR: Well, I think you were the first person I came across who discussed this issue of macro cycling. You also have described it as metabolic flexibility, essentially changing up the composition of your diet. And just to use two broad points for which people can oscillate in between, they may oscillate from a lower carb, higher fat diet and then switch over to a higher carb, lower fat diet. And I believe the fundamental premise here is a healthy metabolism should be flexible, and we also may have evolved with a bit of seasonal oscillation in our macro nutrient composition.

And so, there seems to be an argument there. And I’m really curious to explore more of these details in terms of everything from what we should call this or label this as and who can benefit from it, who may want to be a little bit cautious with it, and I guess everything in between.

So just really briefly here, in case anyone hasn’t come across you before, let’s just start again, briefly, with your background and then we’ll jump into some of this metabolic flexibility and macro cycling.

DrMN: Yeah, thank you. So I did a Bachelor of Arts in Natural Science quite a long time ago. It makes me feel kind of old now. And then did two years postgrad and then a master’s actually in Mechanical Engineering, Biomechanics. I swore I was never going back to school again. Actually, I started working for a medical device company, cardiology stuff. And literally, I just started taking more anatomy, physiology, neurobiology classes for fun. I spent five years doing the Ph.D. program for biomedical engineering that I then dropped out of and went over to exercise physiology at the University of Minnesota, which took about seven years to finish. And then my research there was looking at heart rate variability and metabolic flexibility, which we’ll get into.

And I started working with clients in 2006 through my own business. I did some in-person training, worked at gyms for a while. And just kind of fast-forward through today where I do some online client consults and teach for the Carrick Institute and Rocky Mountain University. Both of those are kind of online, some of the Carrick stuff is in person when needed. And then I also did Flex Diet Certification. So kind of take some of these principles and explain that to coaches and trainers.

DrMR: And you’ve published a number or at least were with others in the publication of a number of research studies, correct?

DrMR: Yeah. And I think that’s really important. The more I’ve had the good fortune to be able to talk with different healthcare providers or researchers, I am thankful for trying to give people the best balance. And I’m talking about the healthcare consumer. We’re trying to provide them with the optimum balance of both forward-thinking science but also clinical reflection.

I really believe that, for the most part, people who are performing both some research and then also working with people in a clinical setting gives you a very rich kind of perspective that’s most able to translate into successful interventions for the public. So I like the fact that you’re kind of straddling the fence between research and clinical practice.

So take us into the world now of metabolic flexibility, carb cycling. And I guess, start us off with some of the terminologies, just so if people are reading different things, we can kind of unite them under a uniform nomenclature and then we can go from there.

DrMN: Yeah, totally. So the official term, metabolic flexibility, was coined by Dr. David Kelley back in probably early 2000. It goes back even further to kind of the crossover theory, it was like the early 90s, from Brooks and Mercier. And what it’s just saying is that there’s this whole debate about, oh, you should be using carbohydrates; no, you should be using fat. What is sort of the best fuel for health and performance? And through metabolic flexibility, the answer is, well, both. It just depends on what you’re doing at that time.

The metabolic flexibility would be how well can you use carbohydrates, let’s say on the high-intensity end of the spectrum or after a very large carbohydrate meal. And now on the other end of the spectrum, how well can you use fat? And the second part to that is how well can you then transition back and forth between those two, which are kind of the two main fuels. We’ll throw—exclude the other kind of minor fuels for now for special cases. And we know that if you look at a disease state, one thing that I like to do is, okay, if that’s a healthy state, do we have any data on opposite end of the spectrum?

So those people get kind of scrunched from both ends of the spectrum. They start losing carbohydrate metabolism to the fullest degree. And over time, as a disease progresses, they actually start losing the ability to entirely use fat. And there’s some very cool work now showing how carbohydrate and metabolism and fat metabolism are pretty related to each other. We always use to think of them as two completely separate things. But we’re learning that they’re much more kind of interrelated than we ever thought before.

Metabolic Flexibility

DrMR: Now, a couple follow-up questions for you there. First one, when you said they’re interrelated, there’s this old saying from, gosh, back in my exercise science undergraduate training, which is, fat burns in the carbohydrate flame, I believe is the way it was termed.

DrMN: Yeah.

DrMR: So does that mean that, in the given meal, people need to add some carbs on with the fat or something different than that?

DrMN: Yeah. And I would say it’s probably a little bit of a stretch. But I’d say that’s been, for the most part, kind of disproved. So where that kind of comes from—and it’s partially true because, at any one point in time, we’re always kind of using a very specific sort of fuel mix, right? If we eat a mixed meal, we’re looking at our fuel that we’re using and we are going to be burning some fat and we are going to be burning some carbohydrates. Now, if you just inhaled two Pop Tarts, you’re definitely going to be more on that carbohydrate end of the spectrum. If you haven’t eaten anything for 24 hours, probably going to be more on the fat end of the spectrum. But even that’s not 100% true, especially on the fat end of the spectrum also.

So from a fuel mix standpoint, it’s kind of true. From a requirement standpoint, it’s not true. So they’re more related—it depends on how technical you want to get, there’s something called glycogen shunt, which their theory states that everything kind of goes through glycogen at some point. So that aerobic fat-based metabolism is kind of supporting the creation of ATP and energy that gets kind of sort of moved up the food chain, so to speak. And that everything at some point is kind of just ATP-PC and maybe some glycogen. But that’s a whole different route.

The other part too is that, when we look at the body as a whole, what we find is like the case of a type 2 diabetic, when you have a muscle, right, so let’s say the muscles are primarily synced that’s burning fat and actually burning carbohydrates, if the insulin sensitivity and everything there gets kind of hosed up, you actually have a further dysregulation potentially caused by incomplete use of fats. So in the past, or what I thought also was that, okay, so we’ve got someone who’s got a carbohydrate-based metabolism problem. They’re a type 2 diabetic. Well, maybe we just need to give them a whole bunch of fat.

But what happens, especially if you put them in a hypercaloric state, that fat can then actually cause and make local insulin resistance even worse. The buildup of what’s called lipotoxicity, ceranamides, and other compounds that paradoxically make the insulin signaling at the muscle level even worse. So I think we also need to differentiate between what fuel is being used? And then also are they in a hypercaloric state or not? You’ve got some companies like VERTIS that are using lower caloric—like a ketogenic diet for type 2 diabetes. And some of the preliminary data are actually really good.

So I think it kind of helps. How I look at it as what fuel are you using and then are you in a situation where you’re just providing more calories in where you’re spending or you’re actually in a hypocaloric situation. And each one of those is going to be a little bit different, which makes it kind of messy.

DrMN: Yeah. So it probably depends if they’re hyper- or hypo- caloric.

DrMR: I’m sorry. And I should say they’re going to be somewhat normocaloric. So they’re not going to intentionally restrict their calories and they’re going to eat the satiation kind of a simple plan. Maybe they’re eating three square meals per day, eating to a point where they’re full, but not feeling stuffed. And I’m assuming that’s going to bring them in a semi-normal caloric energy balance.

DrMN: Yeah, cool. I don’t know.

DrMR: I appreciate you saying that.

DrMN: I mean, you can argue either way. So the gut feeling is that whatever the thing is that they’re having a harder time metabolizing, removing that or lowering that is probably going to be better. Now, the hard part is not all of the data matches that. So if you look at like the latest DIETFITS study, which paradoxically was not intended to determine what macronutrient was the best—

DrMR: Was that Gardner study?

DrMN: Yeah, it’s Gardner. It was designed because they have a lot of very good pilot and other studies showing that, hey, we look at all these trials and they go, what the hell, why is there this massive amount of variability? Why are some people doing really good on X diet and some people aren’t? From a pure public health standpoint, can we try to do something to predict what direction people should go in, right? Because the population level, the question is exactly what you’re asking, which one is the best? Obviously, I can try them and see. But that’s a pain in the ass. I don’t want to do that. Can you do something and tell me which one is going to be better?

DrMR: Sure.

DrMN: And they had some very good genetic data that showed that, hey, if you’ve got these specific gene SNPs—and they only looked at three—that that may tell us some pretty good information about your carbohydrate metabolism. And they did a very cool study, I won’t beleaguer the whole point of that. But very high in, they had both groups on each intervention. So if your genetic profile was positive towards carbs, you had a carb intervention and then you have the opposite condition also.

And in the end, after you take everything all together, they didn’t really see much of a difference on their hypothesis of these three genetic markers may lead us to what macro nutrient profile may be best for people. Another caveat with that too is that they have them scale up in a very intelligent manner. So they had them go to one extreme and kind of scale up from there. And they also did it by focusing on whole food, protein was generally kind of higher depending on what arm you’re in. People ate lots of vegetables and maybe a little bit of fruit. So the diets were very micro nutrient rich and had everything else in there that was beneficial.

So I’m kind of curious to get his elaboration on that. But you make one point, I just kind of want to make sure to echo or at least expound upon a little bit here, which is the genetic testing, yet again, we see another example of where the promise of the genetic testing fell short of where we hoped it would fall.

And again, I am not anti-genetic testing. But I’m pro-logic and I’m pro-truth. And unfortunately, most of what I have examined regarding the allure or ability of genetic testing to help guide our decision making has really been dismal in terms of its performance.

DrMN: Yeah. Hesitance is good.

DrMR: Right.

DrMN: I just did my fourth genetic test that I paid out of my own pocket, more for curiosity and to see if any of it is actionable yet. And some of it is kind of cool and kind of interesting but does it change anything I would do? Minutely, maybe.

DrMR: Right, exactly. Right. And then that’s my peeve, which is some practitioners and educators, what-have-you, again, I think they’re probably doing this under the thinking that this testing is more accurate than it actually is. And so they’re probably doing this in a well-intentioned way. And they’re probably acting perfectly virtuous. But unbeknownst to them, some of what they’re doing is not actually helping people but they are, nonetheless, marketing some of these things as being keys for people who are struggling with X, Y, or Z symptoms.

And so again, I remain open here. But I try to provide a voice of reason for people because I do think that, unfortunately, there are so many interventions in tests, treatments, whatever, you have to consider that knowing what not to do is equally—perhaps even more valuable than knowing what to do. Because if you spend much of your time and resources floundering in things that have no validity then you’re going to burn yourself out with things that won’t get you any closer to your goal.

DrMN: Agreed.

Sponsored Resources

They also have some very exciting research coming in the future. If you haven’t listened to our podcast with Kiran Krishnan who is performing some of this research, you should definitely check it out.

And good news! If you’d like to try Just Thrive, they’re offering 25% off your first purchase when you use the code RUSCIO at checkout (R-U-S-C-I-O). They’re available at ThriveProbiotic.com or on Amazon. Check them out.

More About Metabolic Flexibility

DrMR: So Mike, one thing I wanted to ask you, do you think that metabolic flexibility is a byproduct of health? Meaning, the healthier the individual, the more flexible their metabolism should be. Or is there also a component of this wherein eating a diet that kind of forces metabolic flexibility, like cycling from low carb to high carb, will that improve the health of the host? And again, there may be little bidirectionality there. But curious for the audience to try to help them understand what direction the primary driver may be if you feel the impact is unequivalent in both directions.

DrMN: Yeah. I mean, I think it’s probably a two-way street with that regard. And I’ve always been super interested in what is health and I think of it as cooperation of all systems in your body. So if we just say, okay, what is someone who’s metabolically healthy? What do we say that is? You can look at some blood test and things of that nature and I think you can get a hint. But if I go one step up and go what framework is that playing within. What is the kind of overarching principle that we’re saying, hey, I think this is a marker of health. And my bias is I think metabolic flexibility is a pretty good marker of health. And can you drill farther down into that, look in that bloodwork and things of that nature? Yeah.

When I was initially doing this as part of my Ph.D., the hope was and maybe some people will still kind of run with this, is that could we get that even down to outside of a physician’s office, right? Could we even get that to like a gym or someone who just has a simple metabolic cart? So one of the things I was trying to do is can we get a non-invasive marker for metabolic flexibility? So we get some fancy math with some other stuff on a metabolic cart and some low-intensity work. Because you want to—

DrMR: Explain to people, really quick, Mike, what a metabolic cart is in case they haven’t heard that.

And the initial assumption in exercise textbooks is that, okay, we’ve got a “healthy person”. We take them. We put them on the treadmill. We have them be fasted. They’re doing low-intensity work. And lo and behold, that should show that they’re burning mostly fat as a fuel. And what you find out when you look in the research is the variability on just that marker is super high. So Goedecke has done one of those studies. Heldge did one. I did one. And if you pull them all together, you’re looking at 20% to 90% variation.

Now, these are not necessarily athletes. These are people who are kind of recreational—athletic and generally considered healthy, a lot of times in the younger demographic. And I even had one student who was a little bit overweight but was relatively young, pretty active. And during low-intensity exercise, she was burning almost entirely carbohydrates. So in my brain, I’m thinking, huh. So there’s more variability on that sort of left end of the spectrum than what we think, maybe that’s an early marker for your metabolic health is not headed in the right direction even though your other markers may be able to kind of compensate for that. And again, you could do the other end of the spectrum too, which we don’t see as much of an issue, especially in healthy people. Give them a piss ton of carbohydrates and see how far they can move to the other end.

In research, they’ll do this by doing what’s called an insulin clamp study. But basically, you run a line in your left arm, run a line in your right arm, and they’ll just give you a piss ton of glucose and a piss ton of insulin. And they’re just elevating both to see how your system can handle it. Yeah, it can be used as a marker for metabolic flexibility but you’re definitely going outside of a normal physiologic range. The amount of people that can even do that outside of a research setting are like slim to none too. So practicality is very small.

What we’re trying to do is to get it down to just a simple metabolic, low-intensity test that you could do. We did Gage R&R and showed that the testing is repeatable without an intervention. So if you come back in a lab in the same conditions, same people, different times, the measurement is stable. It doesn’t change. If that changes, well, your measurement is crap and don’t even proceed to the next step.

So the next step hopefully is that we could do some type of intervention and see if the math and everything holds up. So the thought being that maybe it’s a way to potentially screen people without having to do any bloodwork, which opens it up to other professions to run it as a marker of kind of a metabolic health.

Hypoglycemia

DrMR: Got you. Okay. And the other thing I’m wondering here is there are certain patients who are, I’m sure, clients also, and people just in general, who have noticed that they suffer from presumed bouts of hypoglycemia, right? We use the term hypoglycemia to describe I feel tired, jittery, irritable, brain foggy, hangry, what-have-you.

And I guess, once they’ve known—and one question, the question being, would you agree with that, would you add anything to that? And then the statement for people is to make sure to be kind of testing some of these dietary boundaries as you heal and become healthier. Because what I would hate for someone to do is to find success in, let’s say, lower carb frequent meals and then never deviating from that in the future. Because they have labeled themselves as hypoglycemic. And they may be four years out from the interventions still always carrying food around with them and never having really tested the fact that, well, they’re not hypoglycemic or prone to have glycemia anymore because they’ve improved the health of their system, globally. But anything that you would add there, Mike.

DrMN: Yeah. I would agree with that. I mean, I generally see that in people also who are kind of have some issues with exercise, nutrition, things of that nature. I think about it as like—the question that most people want to know is, well, how crappy can I kind of eat? How much variability can I throw into the system and still be okay? Can I not eat for a day and still be okay? Could I have a fair amount of carbohydrates and still be okay?

Because those are kind of the people everyone else is very jealous about. Oh, look at that guy or gal, they didn’t eat yesterday and they seem to be fine. And today, they ate all sorts of stuff and appear to be okay. If we assume that they are metabolically okay, which is a different question. But if we assume that they are, maybe they’re just able to switch and use fat when they need to and use carbs when they need to.

I had some people who would report symptoms of hypoglycemia, sent them to their doc. Their docs are like, oh, they’re fine. And I’m like, huh, that’s weird. I’m like, okay, well, I’m like the next time you have this condition, if you want to, take your own blood glucose. You get an AM reading of where you’re X, you got a good baseline. And we’ll see if it’s different. And my thought was, holy crap, I’m going to see like ungodly little blood glucose and they can go back to their doc and say, look, see, here’s what’s actually going on.

And a few of them, their blood glucose wasn’t really that different. It was on the higher side, but I’m like, huh, that’s weird. It didn’t drop that much. It was down but it wasn’t like in the 60s or 70s and they’re normally running 110. I was like, huh, weird. And so, me being kind of an idiot, I’m like, can I do this to myself? Can I create a situation where I give myself hypoglycemia. And I found that I could, paradoxically, it wasn’t from eating a ton of carbohydrates. It was by sleep depriving myself, train three days in row, and then just had a piss ton of carbohydrates and then went to train again. And stuck my finger, measure my blood glucose. And it was lower but it wasn’t that bad.

DrMR: Did you feel bad at the time?

DrMN: I felt horrible. I mean, I was all shaky. I had a heart rate monitor on. My heart rate went up. And then, who knows if it’s psychosomatic. I went and ate some dates. And like 20 minutes later, it went away. But during that time, that blood glucose didn’t vary that much. And when I look in the literature, there is definitely some very interesting stuff on glycemic variation, which you can look up. There’s a cool study on that. And I’ll be darned if I—I can’t seem to find the study. So if you find it, let me know or if any listeners find it. But I’ve been—I kind of swore I read it. Then again maybe you think you made it up. But I think there was a study looking at that “more healthy people” not like type 2 diabetics, that if they get so tuned in to using blood glucose in that carbohydrate end of the spectrum, that the gain of their system gets changed than altered. Meaning, that they can’t handle much of a low deviation at all. Their blood glucose drops by 10 or 12 points, which isn’t really that big of a deal, to those people because they get locked into this tight gain range. They get massively hypoglycemic symptoms.

And to their body, you could argue that they may be having like sort of hypoglycemic event. But the number doesn’t reflect it. Because their gain range basically got squished, right. Their body is saying, hey, I’m still good at using carbohydrates, that’s all I’ve ever used. I can’t use another fuel source and these are going down at too fast of a rate. So you better do something to fix this problem. Even though the frank number wasn’t necessarily out of range. So again, that’s a theory as to what—

So it sounds like something similar there. And also, I was going to suggest that there could be other hormonal changes that people are sensitive to, most namely I picture catecholamines. Whereas some people might be very sensitive to the ill effects or jittery effects or anxiolytic effects from the catecholamines that help to support blood sugar when someone is going into a shift here. And so the blood sugar would maintain in normal range. But secondary to oscillations in hormones, that may lead to some of the negative symptomatic reactions.

DrMN: Yeah. I 100% agree. Because if your assumption is you can go outside of this tight range, right, your body is going to have a massive reaction to it. And one of the main things is going to be a huge increase in catecholamines, right? So yeah, I look at it from also a kind of an engineering standpoint. If you’re to set up a system and just put it in a heuristic, we can kind of understand does these little theories kind of play out and then they kind of make sense. You can use a concept of gain with all sorts of stuff from receptor density to different systems across the board.

DrMR: Right, right. That makes complete sense. So how do you view may be the evolution of someone’s macronutrient intake? And as we’re having this conversation, what I see emerging is this picture wherein, initially, people may need to eat slightly less carbs. And for the audience, I also discussed this in Healthy Gut, Healthy You, not as directly as I am here. But since you’re recommending that people start with a little bit less carbohydrate intake, not so much for the reason of blood sugar per se or by itself but because also there are other foods that are rich in carbs that people may be prone to reacting to. And this would be FODMAPS, most namely.And then also grains for people who are going to be starting with a Paleo type diet.

So there does seem to be kind of this—at least, what I’m starting to see—evolution starting with a little bit of a lower carb diet. And that does not mean ketogenic, by the way. That just means a partial restriction of carbohydrate. And then as one heals, they can evolve into a broader diet, which could include an increase of carbohydrate and then perhaps even a cycling, as Mike and I are working our way to, which the other thing with this call which is this macro cycling. But Mike, how do you feel about that? Would you poke any holes in that theory?

DrMN: No. I think that’s fine. I mean, at a base level, my simple go-to in the absence of any research that says otherwise is, hey, if you’re not handling or being able to use X, Y, Z so well. Let’s remove it and see what happens, right.

If you don’t handle gluten, let’s remove it and see how you feel, right? If you’re overreacting to just carbohydrates, in general, probably pulling them off for a time period is going to be a good thing. And we know from research, what happens if you remove carbohydrates, in the terms of fasting, which is all sexy now, that you can see some increases in insulin sensitivity, things like that. You can look at some training studies that were done.

If you look at muscle and you look at its ability to use carbs and its effect on insulin. If you do some training while in a low glycogen state, you take some of the carbohydrate out of the muscle and then train. There’s a couple of studies showing that you do see better insulin sensitivity of the muscle. Again, that doesn’t mean the carbs are bad and you should only train fasted and never eat again. But what are you trying to do and what is the outcome of the thing you’re trying to affect? So from that standpoint, yeah, I would agree with that.

Macro-cycling

DrMR: Now, when we’re talking about this issue of macro cycling, one of the main promises that I have heard connected with this is improved metabolism. And that may look like improved cholesterol or improved blood sugar or probably, most chiefly, improved body composition. So there are some that we start off kind of lower carb, they lose some weight, and then they feel like they get stuck and then plateau. And Jason Seib was on a number of months ago, discussing the AltShift Diet, which is essentially this macro cycling back and forth.

There seems to be, as we discussed earlier, some evolutionary possibility to that and even some benefit potentially from stimulating from your metabolic machinery to challenge yourself by adapting to different levels of different macronutrients. So what do you feel for people—for people who are trying to say, okay, should I do this? Should I carb cycle or macro cycle? Should I do this? What would you say the main promise of this is? And could you also connect that to those who should do this and those and those who maybe shouldn’t do this.

DrMN: Yeah. So what I found with people who shouldn’t do it is if people are very stressed or I won’t use the word adrenal fatigue. But people who have these massive amounts of stress, I find that having smaller amounts of carbohydrates, more frequent meals, just tends to help. Maybe because the carbs are buffering cortisol or insulin effects or changing glycemic variability, who knows.

DrMR: Agree.

DrMN: And I’ve talk to you about this. I’ve talked to a lot of other practitioners about it. And I think the one thing that pretty much across the board they all agree on—I know that when I went through that myself, that actually helped me quite a bit. And then in terms of who should or shouldn’t, I always like to have some sort of test of what the capacity or capability is.

But on the other end of the spectrum, you can go with the oral glucose tolerance test, so 80 grams of glucose all at once and measure your response. I usually call it the two Pop Tart test. If you have two Pop Tarts and you pass out on insulin induced stupor under your kitchen table, probably need to work on your carb metabolism a little bit. That doesn’t mean that—I get hate mail from people all the time now, they’re like, you’re telling me I have metabolic problems, I need to eat Pop Tarts. I’m like, no, I’m just saying that as a rough field test, it’s a marker for the far-end of the right end of the spectrum.

So if you can go from the left end to the right end and you’re doing pretty good, yeah, you can use fat pretty good and you can probably use carbohydrates pretty good. So if you’re training a lot and you’ve got a big sink to dump a lot of that fuel through and you’re training with weights and more intense, you may not do much carb cycling. You may do better just pushing carbohydrates up. If you’re like what I’d say more the average person, just the cross-section, most of these people I find will lift maybe three, four days a week. So I’ll push their carbs up a little bit higher on those days to aid their performance in the gym, like maybe Monday, Wednesday, Friday. And then Tuesday, Thursday, maybe they’d do a little bit longer fast in the morning and do some low intensity cardio, try to up regulate the body’s ability to use fat, and then that day is usually a little bit lower carbohydrate.

Now, it is kind of sneaky because by doing that, I’ve also lowered their caloric amount. And I’ve set it up in a way that it’s easier for them to eat a few less calories on that kind of Tuesday, Thursday also. You can change multiple things. You’re changing calories. You’re changing fuel source and things of that nature. But I believe and yeah, research has some pros and cons, I’d say, mostly supported unless you get into extreme like kind of athletic performance with the train low, compete high type stuff, that most of the agreement is that it’s probably a pretty solid approach. Again, there’s going to be individual variation within that and you can kind of titrate that around depending upon what markers you want to use. But I’ve used that just general template as a jumping off point for a lot of people and it appears to work quite well.

DrMR: Got you. And just to recapitulate one of the simple essences of that for people, if you’re highly stressed, you feel like you’re burnt out, you feel sensitive to either high fat or high carb intake, those all might be indicators that this is a bad maneuver for you. And if you feel like you can fast and you’re fairly resilient and fairly non-sensitive to oscillations in your diet, then this may be the right time for you to consider pushing forward into this.

DrMN: Yeah. I was just going to say my caveat is my fear is that people hear the word, oh, you’re doing some fasting Tuesday and Thursday. And you’re like, oh, I just won’t eat for 48 hours. I’m like, no. I’m just saying maybe skip breakfast and go run. Nothing crazy.

DrMR: Sure, sure. And in terms of the benefits people derive from this, I’m assuming body composition is one of the most notable. But please elaborate there.

DrMN: Yeah. So the research studies on kind of approach like that, right, so if you get into—Marquette did one study 2016 in Med and Science in Sport with pretty high-level triathletes, so pretty high VO2. I want to say there in the high 50s or low 60s maybe even. And they did an intervention where they basically played around with glycogen amounts, right. They call it sleep low, train high. So they had one group kind of sleep on low carbohydrates but they purposely depleted their carbohydrates in their muscle. They kind of slept on that “low condition” and then did some more training the next day.

They had the other group, who basically didn’t do that type of intervention at all. They just had the same amount of carbohydrates all the time. And what was interesting, while the study was not primary set up to look at body count, that was secondary outcome, they lost, within three weeks, about 1% body fat on DEXA. So maybe within the limits of what DEXA can detect. But after only a three-week intervention—and what’s fascinating is, the macronutrient amounts were identical between both groups.

But training again on that lowest state, we know, has a lot of different adaptations on enzymes and mitochondria and things of that nature. Now, do those drugs, they translate into body comp and performance changes? Still pretty mixed right now. But those studies are still very early. Because we don’t even know how far do we have to lower muscle glycogen to see an effect if there is an effect. In the early studies, we’re very extreme. So the Marquette one was pretty brutal. Do we have to go? Maybe only in the 30%. So maybe you only have 70% of your glycogen. Maybe that’s enough to trigger these adaptations.

So, hard part is, we don’t know. But my gut feeling is that there’s probably something there that we’ll figure out. Is that going to be useful for most people? Maybe, maybe not. I think the jumping off point for people right now is if they’re feeling good, they’re feeling healthy, their energy is good, just try pushing out one longer period of time to do a fast. I think for most people, that’s beneficial. And that’s what I do with clients a lot of the time if their goal is body comp and performance. It does lower a little glycogen. It does push insulin levels down. It does help with some insulin sensitizing effects. And they find that when people are adapted to it, it’s pretty easy for them to basically just cut out a whole day’s worth of calories too.

I think from a practical side, which is what I was super shocked at that. So I started on that eight years ago. And I had him do a run-in period where they take eight weeks to work out to doing one 24-hour fast. And I was surprised at compliance. Once they get to that point, as long as you allow them that time to adapt, it’s actually really good. I tried doing super low-calorie days, and that was almost always a debacle. Like when you start eating, that’s just like you just want to eat more. I guess just not eating is maybe just easier and you’ve got kind of a hard deadline, you can kind of override it. But just on the compliance side, I found that was actually much better to do.

Integrating Macro-cycling

DrMR: And so how do you recommend integrating all this? There are different philosophies, some people recommend, like you had mentioned a moment ago, on days where you train, you eat carbs or more carbs. And on days when you don’t train, you eat lower carbs. Other people recommend kind of eating with the seasons. And in the spring and fall, eating higher carb. And in the winter and summer, or winter and spring rather, eating lower carb.

So to try to help people who are navigating this, are there a few kind of intelligent entry points with how to design fasting and/or oscillations of carbs into their daily, weekly routine?

DrMN: Yeah. Real quick on the seasons part. I find the whole area fascinating. But I don’t have anyone alter stuff via seasons right now because I don’t think the average human feels the effect of any of the seasons, so it doesn’t matter.

DrMR: Sure, good point.

DrMN: I mean, I live in Minnesota where I’m not turning my heat down to 45 degrees just because it’s winter and putting my parka on because I’m inside. I try to be outside and do stuff like that. But even then, it’s not a lot. So I’m not really sure from the seasonality with the way we’ve overly controlled our environment matters now. Maybe I’m wrong. We’re not bears, we’re not hibernating. Hibernating bears is a fascinating story. But I’ll save that for later.

The terms jumping off point, what I’ll have people do is figure out when you’re doing your weight training days. Like I said, if you’re training Monday, Wednesday, Friday with weights, I would start with higher carbohydrates on that day. So people are like, what’s the number, where do I start at? 200-ish grams for an average pretty healthy guy who’s got average amount of muscle. Reality, I just kind of thrown a dart at a board to guess and that’s just the number that I’ve seen kind of time and time again.

Your body just doesn’t have enough carbs to feel very good. But it doesn’t have enough ketones to have any other energy source. But I find 100, 120 is kind of the low threshold point. And again, most of that, vegetables and fruits and other things like that. Protein, usually about 0.7 grams per pound of body weight, probably a little bit on the minimal side but there’s been a bunch of studies that looked at that now from [Amiro]. Stu Phillips just self-published a meta review that came up to a very similar number as that.

And then fats, it’s on the lower side-ish to start out, 50 to 70 grams, somewhere in there. You start getting, especially with women, you start getting below 50 grams of fat a day and it’s not going to go well. So let’s say that’s in the lower end of the calories too and just slowly start scaling up from there and see how you feel.

DrMR: Got you. And fasting is essentially—in the mornings on those non-training but low-intensity cardio days, is that predominantly who are fasting steps in?

DrMN: Yeah. So I have people do roughly about a 12-hour fast overnight. And sometimes I may extend into 14 depending on when they ate and when they get done training and that type of thing. If they’ve got everything pretty dialed in and their performance is good and they’re like I really want to work on my body comp, but I don’t really want my performance in the gym to go down. Then I would start taking this or that Tuesday or Thursday and eventually have them work out so that would be like a full fasting day of 19 to 24 hours.

DrMR: Got you.

DrMN: I’m not as big a fan of the 16-8. I mean, I know there’s one study, maybe, shows a benefit. And again, I think it depends on the population. And yeah, I’ve had clients in the past who have done that. And their performance was good and they really liked it and it worked for them. So I mean, that’s fine. That’s usually not where I’m going to have somebody start because I find it’s just generally a little bit too restrictive for most people.

DrMR: Okay. So let me make sure I have that all correct here in my head. So let’s say someone’s going to do weight training or more, the more intense training, what we’re terming here as “training”, three days a week: Monday, Wednesday, Friday. On those days, they would have about 200, maybe a little less grams of carbs per day. A little bit less if they are female, roughly. And on the other days, let’s say they’re going to do exercise in the mornings, low intensity cardio on Tuesdays and Thursdays. They’re going to take the weekend, let’s say, completely off. On those days, they’re going to do a low-intensity cardio first thing in the morning, fasted. And that day, their aim for total carbohydrate intake will be 100 to 120 grams, careful not to go less than that. And the fat is going to be between 50 and 70 grams. And is the fat constant or is the fat going to jump between that 50 and 70 depending on their carb intake?

DrMN: Yeah. That’s kind of a minimum threshold. At that point, one of the questions I’ll ask people is, hey, what are your favorite food? If you could eat any food right now, what would it be? And I’m interested to see, do they give me a carbohydrate or they tell me a high fat food? And if they tell me—I had one fitness competitor a couple months ago. And we just did a call and we’re looking at her stuff. And I’m looking at her fat and I’m like, oh, 70. I’m like, that’s definitely on the low end and she’s doing a lot of exercise. Her carbs were very low. And I said, well, if we could add any food to your list right now and let’s just assume you don’t get any body fat or anything like that, let’s just not talk about that for now, what would it be? And she’s like, oh my God, cashew butter. I’m like cashew butter? She’s like, I haven’t had cashew butter for a year. And she’s like I have dreams about cashew butter. I’m like, okay. I’m like, so now, Tuesdays and Thursdays, I add a tablespoon of cashew butter. And she thought I was like the greatest person who ever lived. All I did, because she was hyper nervous about gaining any fat, I just exchanged some of her carbohydrates for fat and calories and they were cashew butter and she thought that was the greatest thing ever.

DrMR: Man, that’s nuts.

DrMN: Because, I mean, once I think you get to the kind of the minimums are covered, unless you’re just really pushing performance hard and need more carbs and there’s a time and a place for that, it probably doesn’t matter a lot. I mean, if you said, yeah, let’s see it all carbs, high protein, and like 10 grams of fat, oh you’re going to run into a world of hurt, you know what I mean? But once you get kind of through those kinds of minimums, which they’re kind of arbitrary, there’s more of a wiggle room than you can kind of customize stuff for people’s compliance. And then I just monitor their performance. If our carbs get too low, their performance is going to start dropping. So then we’re going to have to decide what we want to do at that point then.

DrMR: Sure. That makes a lot of sense.

DrMR: So that I can tell that you’re a seasoned clinician with this stuff because you’re—and some of those simple observations of what’s the practical maneuver we can make here that would really enhance someone’s quality of life and still work within the objective that we’re trying to achieve dietarily, for example, the cashew butter. And sometimes people get so confined into these rigid rules and I think they make things harder than they have to be. And they lose sight of the fact that as long as you’re achieving the high-level objective, the details oftentimes don’t make a big deal one way or the other.

DrMN: No. I mean, I’ve had bros who do heavy lifting. And I mean, you’ve been down there in Costa Rica and stuff too. And guys have 350 grams of carbs on some days and eat ice cream at night, okay. But people will go, oh, that’s so crazy. I’m like, but they eat so much other food and vegetables and everything else like you’re telling me 5 ounces of Moose Tracks ice cream three nights a week, that’s what’s going to kill their metabolism or give them diabetes? Please.

DrMR: Right.

DrMN: It just goes away. It doesn’t make any damn sense.

DrMR: Sure.

Everyone wants to look at a food and be like, oh, that’s a horrible food, don’t have that. Well, maybe for one person but maybe not for the other person.

DrMR: Context matters. Absolutely.

DrMN: Yeah. And you start doing like the continuous glucose monitor stuff and like we saw pineapple sent some people through the roof. Ice cream was fine. Other people, pineapple, pfft, barely moved at all.

DrMR: Right.

DrMN: And they’re like, wow, that’s crazy.

DrMR: Do you think that that’s something that has a high amount of potential utility for people who are struggling with body comp trying to connect with a continuous glucose monitor to weed out the foods that may really be spiking their blood sugar. I know Rob Wolfe has really gone into this study in detail.

DrMN: I think so. I mean, I know Rob has talked about the study too, the study from a couple of years ago, that’s just a massive study to look at and like that the gut biome and a bunch of other stuff. And the fascinating part was I was like one of the first huge studies to show that there is this massive variation from one person to the next. So how I look at it is if there’s a guy who comes to me and who’s lifting a lot and they really are pushing carbohydrate intake, but he’s like, I’m getting in my later 30s, early 40s and I’m a lot more concerned about my health now than I used to be. So we can slap one of those on them and then see what point does he go over, where he’s just getting really high, and at one point did different foods make a difference.

As you know from blood work, which I got from Dr. Brian Walsh, you can look at like GlycoMark, will give you an idea of how often or they’re having these massive excursions of blood glucose that goes sky high but then rapidly comes back down again. So it’s not going to get picked up kind of like an HbA1c or an average. So I think as technology gets better, we’re going to have a lot better idea of all that. And then when I did it, I was interested in frankly how bad can I eat and can I still stay in the physiologic range?

DrMR: True.

DrMN: Because, if I’m like, if I’m the person yammering about metabolic flexibility because half a cookie in breakfast like sends me sky high.

And I had two Pop Tarts and two cookies and I’d hit like 120, 130. I had like one barely hypoglycemic episode and I had some days where I’d eat like seven times a day, just to see what happens. That’s only for two weeks, right.

But it was interesting that when I was more restrictive, I think I was a lot more sensitive. And during that time, my sleep was good and just even the low-intensity movement was a lot better too. I think all those things add up and it gives us a way to kind of peer a little bit under the hood and see what’s actually going on. And I’ve seen with some people who do like a very hard ketogenic approach, their carbohydrate tolerance kind of goes down quite a bit, which is probably not an issue if that’s where you’re staying and you’re happy doing that, everything is good, probably not that big of a deal. But if you’re someone who goes in and out of ketosis a lot, I don’t know.

There’s one study from Wilson’s lab 2017 that put people on a cyclic ketogenic diet and a group that was not on a cyclic ketogenic diet. And the cyclic ketogenic diet actually lost lean mass. I don’t know how much I trust that data because I know how long it was spent in peer review. But if it’s replicated, it makes you wonder.

So I think going in and out of ketosis is very hard. I tell people like if you’re going to do it, just go all in and go for it. I see a lot of targeted ketogenic diets and all this stuff now and I don’t know, bodybuilders tried that years ago like some Arnold stuff from the 80s. And unless you’re on a massive amount of drugs, it didn’t seem to work so well.

DrMR: That’s one of the key variables in bodybuilding we have to account for, isn’t it?

So yeah. What’s fascinating though is if you do fasting, the transition doesn’t appear to be that hard, probably because PTH enzyme doesn’t change. So I could have someone go really high carb Monday do kind of a longer fast or even a full fast Tuesday and then go back to doing super high carb again on Wednesday and it appears to be just fine. And there’s no PTH enzyme down-regulation that we’ve seen yet either.

DrMR: So bouts of fasting rather than bouts of ketotic dieting you think would be a better strategy?

DrMN: Yeah, right now, I mean, that’s by far, my preference. I got to finish the damn article on that. But because most people say, okay, why do you want to do a ketogenic diet? So we threw pathology aside, if you got a TBI or something like that, I got it. I got you. There’s lots of good data on that epilepsy whatever.

But if you’re a moderately healthy individual and you’re like, yeah, I’m nervous about having my insulin be high, my glucose is a little high. I kind of want to work on body comp a little bit. I’m like, huh, okay, we can accomplish pretty much all of those things in most people by having you do a longer fast probably or maybe even once a week or maybe a little longer overnight fast. I don’t think people need to go to a ketogenic diet to accomplish that.

Especially if they’re already doing habits that we’d want them to do anyway like weight training and movement and things of that nature.

Episode Wrap-up

DrMR: Sure, sure. Well, Mike, this has been great conversation as I thought it would be. And hopefully help people realize that some of these changes to be made are not that complicated. And they’d walk away with some items to experiment with. Would you want to offer people anything in close and then would you also tell people where they can track you down and learn more about you and your work.

DrMN: Yeah. The only thing I would add in closing is the template I outlined also works really well, if people are worried about longevity. So if you look at longevity real quick, so top markers are lower body strength, grip strength, and VO2 max. Those are things we know from intervention trials that are supportive of things people can do to extend their life. So your fasting days, you’re upregulating your AMPK, maybe you get some autophagy, who knows to how much. But the other days, you’re still using mTOR to run muscle repair and to get stronger and to keep lean body mass and strength. So I think it’s a nice hybrid for people who kind of have that as their goal also.

But yeah, if you want to find more information, just miketnelson.com, M-I-K-E-T-N-E-L-S-O-N. There should be a little box at the top there where you can sign up for the newsletter. Most of the information I send out actually just goes through the exclusive newsletter there and they’ll be—otherwise, people can contact me there.

DrMR: Awesome. Well, thank you sir. Keep doing what you’re doing. It’s great stuff. And I’m sure we’ll probably have you back on at some point in the future.

DrMN: Yeah, thank you very much for all the great stuff and the good conversation and the awesome questions. So I love it.

DrMR: Thanks, buddy. Talk to you soon.

DrMN: Thank you.

What do you think? I would like to hear your thoughts or experience with this.

- Get help using this information to become healthier.

- Get your personalized plan for optimizing your gut health with my new book.

- Healthcare providers looking to sharpen their clinical skills, check out the Future of Functional Medicine Review Clinical Newsletter.

Dr. Ruscio is your leading functional and integrative doctor specializing in gut related disorders such as SIBO, leaky gut, Celiac, IBS and in thyroid disorders such as hypothyroid and hyperthyroid. For more information on how to become a patient, please contact our office. Serving the San Francisco bay area and distance patients via phone and Skype.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!