Early Signs of Dementia Checklist: What to Look For

How to Support Brain Health and Decrease the Risk of Dementia

- About Dementia|

- Cognition vs. Memory|

- How Early Can We Spot Dementia|

- Early Signs of Dementia|

- Addressing Cognitive Decline|

- Improving Brain Health|

- Daily Brain Health Checklist|

- Recommended Products|

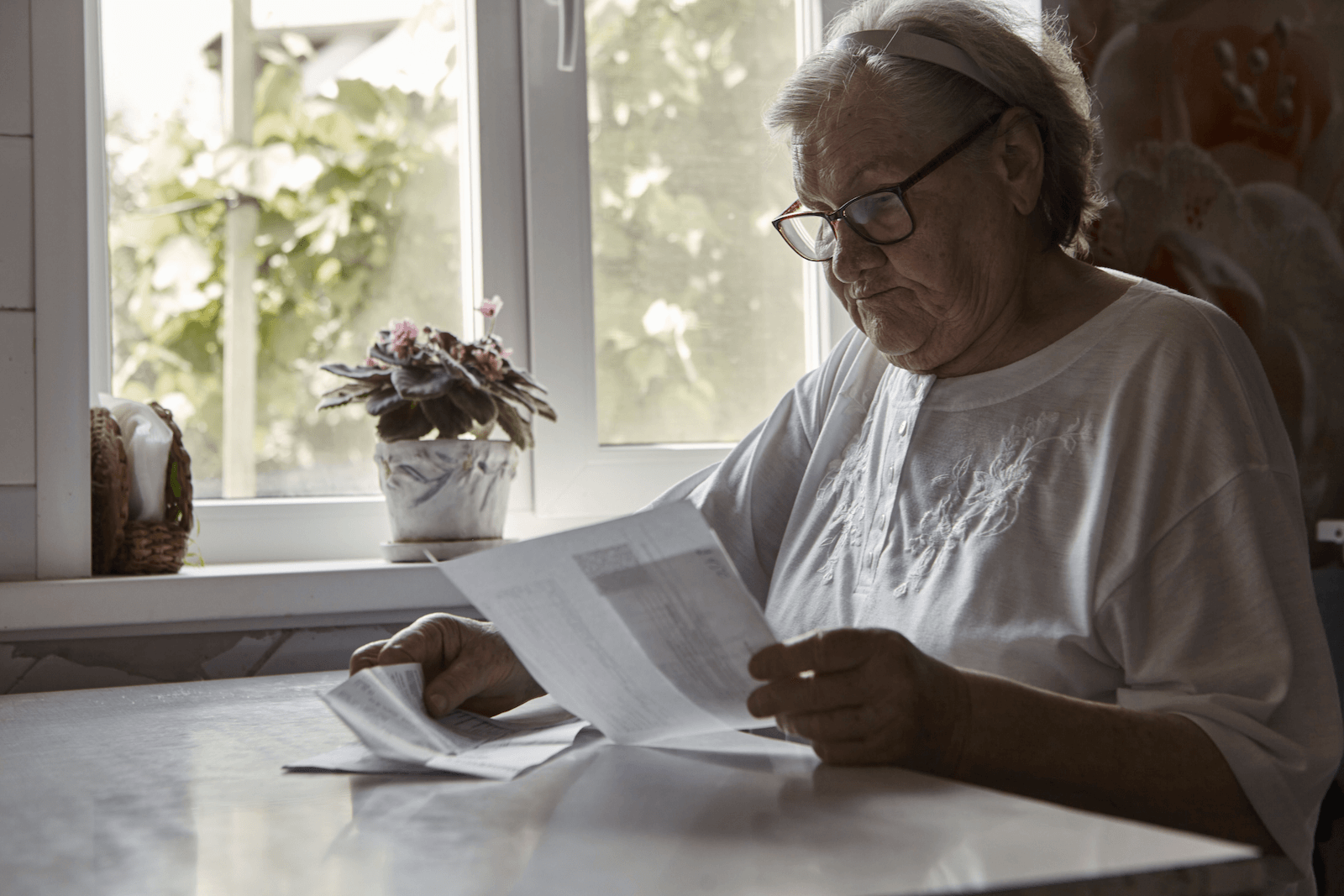

- Some of the first signs of dementia are difficulty completing everyday tasks such as paying bills and cooking, increased irritability, struggling to make decisions that used to be easy, and getting lost while driving.

- Dementia is caused by a combination of genes and environment, and we do not currently have a definitive cure or prevention.

- Warning signs of dementia can show up as early as 18 years before diagnosis.

- Improving diet and lifestyle with an anti-inflammatory diet, probiotics, exercise, and good sleep hygiene are keys to improving brain health if you are noticing early signs of dementia.

With nearly 50 million people worldwide living with dementia and cases expected to triple by 2050, especially because of the aging Baby Boomer generation, you may be wondering how to prevent dementia or identify it early [1]. The good news is that there are some early signs you can look out for– and living a brain healthy lifestyle with an anti-inflammatory diet, exercise, and sleep can help to support brain health and cognition, potentially decreasing the risk or onset of early dementia.

This article will discuss the early signs of dementia and simple tips for living a brain healthy life to help decrease the risk of memory loss.

What Is Dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term for anything that causes a continuous decline in memory and thinking skills that severely decrease quality of life and ability to function [1].

You are probably most familiar with Alzheimer’s Disease, which causes 70-80% of dementia cases. However, there are many other types of dementia [1].

These are the most common forms of dementia:

Alzheimer’s: This causes 70%-80% of all cases of dementia. Memory problems and cognition loss occur when two proteins found in the brain, beta-amyloid proteins and tau proteins, either accumulate or become abnormal, form plaques and deposits in the neurons, and cause them to degenerate [1].

Vascular dementia: This is the second most common form of dementia, found in 5-10% of all cases. It’s caused by decreased blood flow to the brain for any number of reasons. The most common risk factors are high cholesterol, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking [1].

Lewy body dementia: This causes 5-10% of all dementia cases. It’s often called “dementia with Parkinson’s” because people experience the same gait changes and tremors found in Parkinson’s disease [1].

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD): This is the second most common form of dementia in people under 65 years old. It affects the front of the brain and often comes with problems speaking first [1].

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: This is a fatal and quickly progressing neurodegeneration. It only occurs in one in 1 million people [1].

Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome: The syndrome occurs in 1-2% of cases and is often related to overconsumption of alcohol [2].

Mixed dementia: This refers to when a person has two or more types of dementia at once [1].

Understanding Symptoms of Dementia: Cognition vs. Memory

Early signs of Alzheimer’s and other dementias include not only what we think of as typical memory loss (forgetting facts, names, and events) but also cognition (our ability to use all our memories to make complex decisions). So, what’s the difference between cognition and memory, and why does that matter?

A memory is a stored pattern created by the neurons in the brain. Memory involves both manipulating and storing knowledge. In the brain, we constantly receive information (from input like an event, learning a new hobby, reading, or from something we see, smell, or hear). Our brain works with that knowledge and either uses it right away (short-term memory) or stores that information in different ways for later use (long-term memory).

Cognition includes all forms of knowing, from knowing a process, to thinking through a chain of events, problem-solving, abstract thinking (understanding complex topics like empathy or compassion), and making decisions [3]. Cognition is more about how our brain chunks information and allows us to use it for decisions and processing. For example, remembering that a stove is hot and if we touch it, we get burned, helps us decide to put oven mitts on our hands before we take something out of the oven.

Cognition includes memory, and we need memory in order to have cognitive ability. When we’re talking about memory or brain function, we’re also talking about cognitive ability — how our brain processes and uses stored information (memories). This is why people undergo cognitive testing as part of a dementia diagnosis. In dementia, we need to not only know how memory is working but also how the cognitive process is working.

When Can We Spot Dementia?

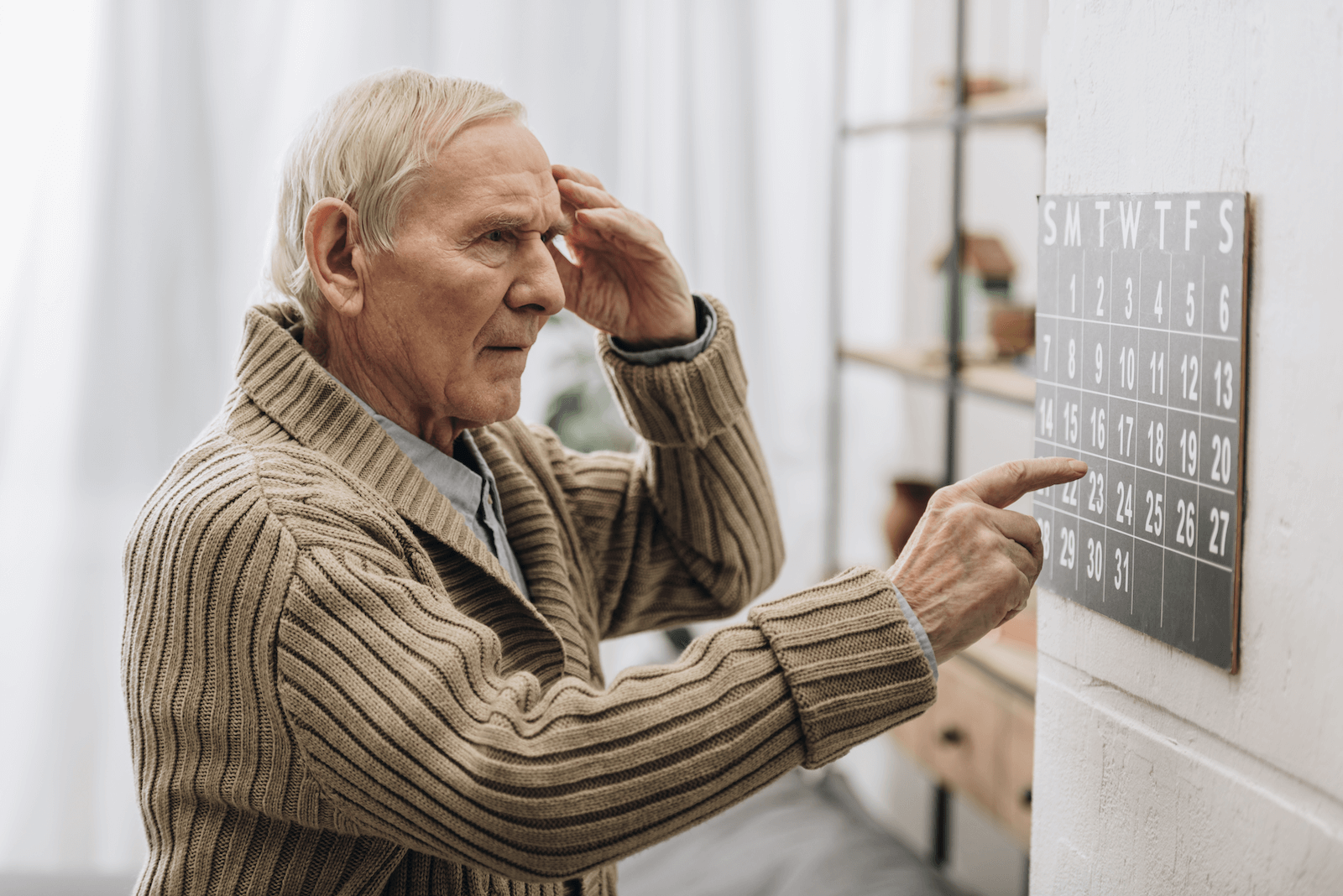

Some people report very early signs of dementia decades before diagnosis (around ages 40-60). These include loss of smell in people with Lewy body dementia, progressive trouble remembering names of people and items, consistent loss of daily items such as keys, changes in gait (trouble balancing, dragging feet, lopsided walk), and trouble comprehending learned information from books and reading materials [4, 5].

It is important to remember that all brains are different and some people are just more forgetful than others. A new and progressive change in memory function or forgetfulness may indicate very early stages of dementia or another brain health issue. A change in cognitive function or ability to complete daily tasks (such as those listed below) should be checked by a neurologist.

Early Signs of Dementia Checklist

A person struggling with memory may not notice these early changes or may chalk them up to typical forgetfulness. However, family members often notice them. These changes in one’s ability to function in daily life are important indicators of brain health:

- Trouble sequencing: This is one of the earliest signs of dementia, and it can be hard to spot. Sequencing is our ability to follow the steps to complete a task, such as buttoning a shirt, balancing a checkbook, cooking, driving, feeding the dog, or remembering your partner asked you to get meat from the fridge and then cook it. It is hard to spot because at first, sequencing is not lost but slowed. So, the noticeable symptom often looks like frustration or anger [6, 7].

- Trouble finding words: We all forget words sometimes, but if you have consistent trouble finding the right words in a conversation, that may indicate a problem with cognitive function [1].

- Personality changes: These can include rapid mood swings, becoming more easily irritated and overwhelmed during social activities, angry when completing common tasks such as cooking or using email, or less concerned about safety or cleanliness [1].

- Impairment of decision-making: Needing a longer time to make decisions or having poor judgment. Examples can include spending large sums of money or even an inability to choose an item off of a menu [1].

- Disorientation: This means being disoriented when going from one familiar place to another, such as being confused as to why you are walking from the family room to the kitchen during a holiday, or being unable to find your way while driving to a favorite restaurant [1].

- Impaired spatial awareness: Spatial awareness is the ability to discern the distance between two objects. People with poor spatial relationships struggle to know how far apart things are, so they may drive over curbs, miss the table when placing a cup down, or struggle to find buttons on a shirt [8].

What if I Have Early Signs of Dementia?

If you are having serious dementia-like symptoms, the path to improving your brain health lies in addressing some of the root causes of cognitive decline.

Always check with your health professional if you experience a change in your ability to complete everyday tasks to rule out any possibility of stroke, traumatic brain injury, or other acute injury to the brain. If you are not struggling with any of those issues, some of the most common problems that lead to cognitive decline are related to the brain/gut axis or even the brain liver axis.

The Gut-Brain Connection

The health of our gut directly influences the health of our brain. Here are a few examples:

- Neurotransmitters that affect mood, such as dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, are made in the gut and travel to the brain along the vagus nerve [9, 10].

- An imbalanced gut microbiome can lead to leaky gut and inflammation, which can lead to improper communication between the gut and brain [11, 12].

- There is also a gut-brain-liver connection. A type of cognitive impairment that occurs in liver disease is called hepatic encephalopathy (HE). In HE, the liver does not do an adequate job of filtering toxins from the blood, and those toxins can travel to the brain. HE has been linked to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) which is an imbalance of gut bacteria [13, 14, 15, 16, 17].

Tips for Improving Brain Health

The best place to start with improving your gut and brain health is with diet and probiotics. Let’s take a look.

Diet and Dementia

You can start by eating an anti-inflammatory diet. This can help heal any damaged gut lining, balance the gut microbiome, and remove any microbes (bacteria or fungi) that may be causing a gut microbiome imbalance. As a result, it can improve memory, mood, and cognition [18, 19, 20, 21].

Managing your metabolic health and weight is critical for preventing Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

A lower amount of processed and sugary foods can help even out blood sugar levels. Alzheimer’s has been nicknamed “type 3 diabetes” because Alzheimer’s disease can develop when brain cells become insulin resistant and can no longer use glucose properly [22].

I recommend starting with a Paleo diet, which removes inflammatory foods such as gluten, dairy, and legumes.

Here’s what the research says about anti-inflammatory diets and cognitive decline:

- Low inflammatory diets have been shown to improve cognitive decline in people with dementia. The Mediterranean diet (a lower inflammatory diet rich in whole foods, fresh fruit and vegetables, oily fish like sardines, and healthy fats like olive oil) and ketogenic diets (foods similar to the Mediterranean diet but also and very low carbohydrate) are the most studied low-inflammatory diets [23, 24, 25]. We find that many of our patients have success with a Paleo diet, which is a less studied but well balanced anti-inflammatory diet.

- An anti-inflammatory diet can help to resolve metabolic syndrome, which may contribute to early signs of dementia [26].

Research suggests that other dietary interventions can also be helpful for Alzheimer’s patients:

- A 2020 systematic review evaluated the effect of ketogenic interventions (extreme carbohydrate restriction) on patients with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment [24]. Ketogenic interventions were generally effective in improving general cognition, episodic memory (memory of past experiences), and secondary memory (long-term storage and recall of information).

- Another systematic review published in 2020 looked at dietary interventions for Alzheimer’s patients more broadly. The researchers concluded that the effects of most dietary interventions are inconclusive and better research is needed [27]. However, omega-3 fatty acids, probiotics, ginseng, inositol, and specialized nutritional formulas appeared to have positive effects on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease.

It is important to note that more research needs to be done on how diet affects cognitive function, as studies are inconsistent and some studies don’t show a large improvement with diet changes [25, 27].

Probiotic Support

Probiotics support your gut and help to improve the gut-brain axis by balancing the gut microbiome. Improving the gut microbiome has shown to be beneficial for people with cognitive decline and even Alzheimer’s disease:

- Two clinical trials have demonstrated that supplementing with probiotics for 12 weeks can improve cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s [28, 29].

- Probiotics have been shown to improve brain function in hepatic encephalopathy [17, 30, 31].

- Probiotics may improve cognitive function, especially word finding [28, 29, 32, 33, 34, 35].

- Multiple clinical trials have shown that probiotics change the makeup of the gut microbiome and improve cognitive function and mood [34, 36]. They may even help improve long-term memory [37].

Here is a simple chart to show you how you can add probiotics into your life:

Every probiotic falls into one of three categories: lactobacillus & bifidobacterium species blend, saccharomyces boulardii, and soil-based probiotics. In order to have a balanced probiotic plan, follow our three-for-balance probiotic protocol and choose one probiotic from each category.

In addition to addressing the gut-brain axis, two other important components can help support good cognition and brain health: sleep and exercise.

Optimize Exercise and Sleep

Exercise is beneficial to the brain because it:

- Supports the neural connections between movement of the body and the brain, improving gait. Gait change is an early sign of dementia and indicator of progression of disease [5].

- Supports blood flow to the brain, which can be particularly helpful in vascular dementia [38, 39].

- Decreases leaky gut and supports the brain-gut axis [40, 41].

- Can improve cognition and executive functioning in people with dementia [42, 43].

- Increases BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), which is important in supporting neuroplasticity and, thus, memory and learning [44].

- Allows us to learn new things through sports, which supports brain function and cognition [45, 46].

- Improves sleep, which is essential for brain health and memory, as we discuss below [47, 48].

Sleep is essential for the brain. Inadequate sleep can contribute to brain fog, difficulty focusing, difficulty learning, dementia (by leading to elevated amyloid plaque in the brain,) and poor memory [49, 50].

Tips for better sleep:

- Sleep consistency and routine: Try to go to bed and wake up at the same time each day, even on weekends. Get ready for bed in the same way each day.

- Block blue light: Turn off electronics and wear blue light blocking glasses two hours before bed to help start melatonin production [51].

- Block all light in your room: Use blackout curtains, covering lights from chargers and/or wearing a good sleep mask.

- Regulate temperature: Most people sleep best in a room that is around 60 degrees Fahrenheit.

Your Daily Brain Health Checklist

Now that you know some of the early signs of dementia, let’s review the basics of good brain health you can practice every day:

- Anti-inflammatory and gut healing diet

- Consistent exercise

- Sleep well

If you are unsure about the state of your cognition or memory and want personalized help, please reach out to our clinic.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.➕ References

- Emmady PD, Tadi P. Dementia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. PMID: 32491376.

- Covell T, Siddiqui W. Korsakoff Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. PMID: 30969676.

- APA Dictionary of Psychology [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jul 21]. Available from: https://dictionary.apa.org/cognition

- Olichney JM, Murphy C, Hofstetter CR, Foster K, Hansen LA, Thal LJ, et al. Anosmia is very common in the Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2005 Oct;76(10):1342–7. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.032003. PMID: 16170073. PMCID: PMC1739380.

- Beauchet O, Allali G, Berrut G, Hommet C, Dubost V, Assal F. Gait analysis in demented subjects: Interests and perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008 Feb;4(1):155–60. DOI: 10.2147/ndt.s2070. PMID: 18728766. PMCID: PMC2515920.

- Roll EE, Giovannetti T, Libon DJ, Eppig J. Everyday task knowledge and everyday function in dementia. J Neuropsychol. 2019 Mar;13(1):96–120. DOI: 10.1111/jnp.12135. PMID: 28949080.

- Okazaki M, Kasai M, Meguro K, Yamaguchi S, Ishii H. Disturbances in everyday life activities and sequence disabilities in tool use for Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2009 Dec;22(4):215–21. DOI: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181b278d4. PMID: 19996873.

- Possin KL. Visual spatial cognition in neurodegenerative disease. Neurocase. 2010 Dec;16(6):466–87. DOI: 10.1080/13554791003730600. PMID: 20526954. PMCID: PMC3028935.

- Arneth BM. Gut-brain axis biochemical signalling from the gastrointestinal tract to the central nervous system: gut dysbiosis and altered brain function. Postgrad Med J. 2018 Aug;94(1114):446–52. DOI: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135424. PMID: 30026389.

- Tran N, Zhebrak M, Yacoub C, Pelletier J, Hawley D. The gut-brain relationship: Investigating the effect of multispecies probiotics on anxiety in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of healthy young adults. J Affect Disord. 2019 Jun 1;252:271–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.043. PMID: 30991255.

- Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Irritable bowel syndrome: a microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder? World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct 21;20(39):14105–25. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14105. PMID: 25339800. PMCID: PMC4202342.

- Bravo JA, Julio-Pieper M, Forsythe P, Kunze W, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, et al. Communication between gastrointestinal bacteria and the nervous system. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012 Dec;12(6):667–72. DOI: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.09.010. PMID: 23041079.

- Zhang Y, Feng Y, Cao B, Tian Q. The effect of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth on minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Arch Med Sci. 2016 Jun 1;12(3):592–6. DOI: 10.5114/aoms.2015.55675. PMID: 27279853. PMCID: PMC4889679.

- Caraceni P, Vargas V, Solà E, Alessandria C, de Wit K, Trebicka J, et al. The use of rifaximin in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2021 Jan 9; DOI: 10.1002/hep.31708. PMID: 33421158.

- Flamm SL, Mullen KD, Heimanson Z, Sanyal AJ. Rifaximin has the potential to prevent complications of cirrhosis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018 Sep 28;11:1756284818800307. DOI: 10.1177/1756284818800307. PMID: 30283499. PMCID: PMC6166307.

- Abid S, Kamran M, Abid A, Butt N, Awan S, Abbas Z. Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy: Effect of H. pylori infection and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth treatment on clinical outcomes. Sci Rep. 2020 Jun 22;10(1):10079. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-67171-7. PMID: 32572109. PMCID: PMC7308324.

- Zhang Y, Feng Y, Cao B, Tian Q. Effects of SIBO and rifaximin therapy on MHE caused by hepatic cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015 Feb 15;8(2):2954–7. PMID: 25932262. PMCID: PMC4402909.

- Chen X, Maguire B, Brodaty H, O’Leary F. Dietary patterns and cognitive health in older adults: A systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67(2):583–619. DOI: 10.3233/JAD-180468. PMID: 30689586.

- Lehert P, Villaseca P, Hogervorst E, Maki PM, Henderson VW. Individually modifiable risk factors to ameliorate cognitive aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Climacteric. 2015 Oct;18(5):678–89. DOI: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1078106. PMID: 26361790. PMCID: PMC5199766.

- Riccio P, Rossano R. Undigested food and gut microbiota may cooperate in the pathogenesis of neuroinflammatory diseases: A matter of barriers and a proposal on the origin of organ specificity. Nutrients. 2019 Nov 9;11(11). DOI: 10.3390/nu11112714. PMID: 31717475. PMCID: PMC6893834.

- Orchard TS, Gaudier-Diaz MM, Weinhold KR, Courtney DeVries A. Clearing the fog: a review of the effects of dietary omega-3 fatty acids and added sugars on chemotherapy-induced cognitive deficits. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(3):391–8. DOI: 10.1007/s10549-016-4073-8. PMID: 27933449. PMCID: PMC5526680.

- de la Monte SM. Type 3 diabetes is sporadic Alzheimer׳s disease: mini-review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014 Dec;24(12):1954–60. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.06.008. PMID: 25088942. PMCID: PMC4444430.

- Petersson SD, Philippou E. Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and dementia: A systematic review of the evidence. Adv Nutr. 2016 Sep 15;7(5):889–904. DOI: 10.3945/an.116.012138. PMID: 27633105. PMCID: PMC5015034.

- Grammatikopoulou MG, Goulis DG, Gkiouras K, Theodoridis X, Gkouskou KK, Evangeliou A, et al. To keto or not to keto? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials assessing the effects of ketogenic therapy on alzheimer disease. Adv Nutr. 2020 Nov 16;11(6):1583–602. DOI: 10.1093/advances/nmaa073. PMID: 32597927. PMCID: PMC7666893.

- Radd-Vagenas S, Duffy SL, Naismith SL, Brew BJ, Flood VM, Fiatarone Singh MA. Effect of the Mediterranean diet on cognition and brain morphology and function: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018 Mar 1;107(3):389–404. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqx070. PMID: 29566197.

- Pasinetti GM, Eberstein JA. Metabolic syndrome and the role of dietary lifestyles in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2008 Aug;106(4):1503–14. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05454.x. PMID: 18466323. PMCID: PMC2587074.

- Moreira SC, Jansen AK, Silva FM. Dietary interventions and cognition of Alzheimer’s disease patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled trial. Dement Neuropsychol. 2020 Sep;14(3):258–82. DOI: 10.1590/1980-57642020dn14-030008. PMID: 32973980. PMCID: PMC7500808.

- Akbari E, Asemi Z, Daneshvar Kakhaki R, Bahmani F, Kouchaki E, Tamtaji OR, et al. Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Cognitive Function and Metabolic Status in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Double-Blind and Controlled Trial. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016 Nov 10;8:256. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00256. PMID: 27891089. PMCID: PMC5105117.

- Tamtaji OR, Heidari-Soureshjani R, Mirhosseini N, Kouchaki E, Bahmani F, Aghadavod E, et al. Probiotic and selenium co-supplementation, and the effects on clinical, metabolic and genetic status in Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2019 Dec;38(6):2569–75. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.11.034. PMID: 30642737.

- Dalal R, McGee RG, Riordan SM, Webster AC. Probiotics for people with hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb 23;2:CD008716. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008716.pub3. PMID: 28230908. PMCID: PMC6464663.

- Flamm SL. Rifaximin treatment for reduction of risk of overt hepatic encephalopathy recurrence. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011 May;4(3):199–206. DOI: 10.1177/1756283X11401774. PMID: 21694804. PMCID: PMC3105611.

- Lv T, Ye M, Luo F, Hu B, Wang A, Chen J, et al. Probiotics treatment improves cognitive impairment in patients and animals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021 Jan;120:159–72. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.10.027. PMID: 33157148.

- Lew L-C, Hor Y-Y, Yusoff NAA, Choi S-B, Yusoff MSB, Roslan NS, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum P8 alleviated stress and anxiety while enhancing memory and cognition in stressed adults: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(5):2053–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.09.010. PMID: 30266270.

- Kim C-S, Cha L, Sim M, Jung S, Chun WY, Baik HW, et al. Probiotic Supplementation Improves Cognitive Function and Mood with Changes in Gut Microbiota in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021 Jan 1;76(1):32–40. DOI: 10.1093/gerona/glaa090. PMID: 32300799. PMCID: PMC7861012.

- Roman P, Estévez AF, Miras A, Sánchez-Labraca N, Cañadas F, Vivas AB, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial to explore cognitive and emotional effects of probiotics in fibromyalgia. Sci Rep. 2018 Jul 19;8(1):10965. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-29388-5. PMID: 30026567. PMCID: PMC6053373.

- Hwang Y-H, Park S, Paik J-W, Chae S-W, Kim D-H, Jeong D-G, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Lactobacillus Plantarum C29-Fermented Soybean (DW2009) in Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A 12-Week, Multi-Center, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2019 Feb 1;11(2). DOI: 10.3390/nu11020305. PMID: 30717153. PMCID: PMC6412773.

- Kobayashi Y, Kuhara T, Oki M, Xiao JZ. Effects of Bifidobacterium breve A1 on the cognitive function of older adults with memory complaints: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Benef Microbes. 2019 May 28;10(5):511–20. DOI: 10.3920/BM2018.0170. PMID: 31090457.

- Cass SP. Alzheimer’s disease and exercise: A literature review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2017;16(1):19–22. DOI: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000332. PMID: 28067736.

- Hussenoeder FS, Riedel-Heller SG. Primary prevention of dementia: from modifiable risk factors to a public brain health agenda? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018 Dec;53(12):1289–301. DOI: 10.1007/s00127-018-1598-7. PMID: 30255384.

- Petersen AMW. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005 Apr 1;98(4):1154–62. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00164.2004. PMID: 15772055.

- Ticinesi A, Lauretani F, Tana C, Nouvenne A, Ridolo E, Meschi T. Exercise and immune system as modulators of intestinal microbiome: implications for the gut-muscle axis hypothesis. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2019;25:84–95. PMID: 30753131.

- Biazus-Sehn LF, Schuch FB, Firth J, Stigger F de S. Effects of physical exercise on cognitive function of older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020 May 12;89:104048. DOI: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104048. PMID: 32460123.

- Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition for older adults with glucose intolerance, a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):569–79. DOI: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100768. PMID: 20847403. PMCID: PMC3049111.

- Miranda M, Morici JF, Zanoni MB, Bekinschtein P. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Key Molecule for Memory in the Healthy and the Pathological Brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019 Aug 7;13:363. DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00363. PMID: 31440144. PMCID: PMC6692714.

- Park IS, Lee KJ, Han JW, Lee NJ, Lee WT, Park KA, et al. Experience-dependent plasticity of cerebellar vermis in basketball players. Cerebellum. 2009 Sep;8(3):334–9. DOI: 10.1007/s12311-009-0100-1. PMID: 19259755.

- Niemann C, Godde B, Staudinger UM, Voelcker-Rehage C. Exercise-induced changes in basal ganglia volume and cognition in older adults. Neuroscience. 2014 Dec 5;281:147–63. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.033. PMID: 25255932.

- Campbell KL, Zadravec K, Bland KA, Chesley E, Wolf F, Janelsins MC. The Effect of Exercise on Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment and Applications for Physical Therapy: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Phys Ther. 2020 Mar 10;100(3):523–42. DOI: 10.1093/ptj/pzz090. PMID: 32065236.

- Jurado-Fasoli L, De-la-O A, Molina-Hidalgo C, Migueles JH, Castillo MJ, Amaro-Gahete FJ. Exercise training improves sleep quality: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020 Mar;50(3):e13202. DOI: 10.1111/eci.13202. PMID: 31989592.

- Wigren H-K, Stenberg T. [How does sleeping restore our brain?]. Duodecim. 2015;131(2):151–6. PMID: 26237917.

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000 Jun;21(3):383–421. DOI: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. PMID: 10858586. PMCID: PMC3887148.

- Tähkämö L, Partonen T, Pesonen A-K. Systematic review of light exposure impact on human circadian rhythm. Chronobiol Int. 2019 Feb;36(2):151–70. DOI: 10.1080/07420528.2018.1527773. PMID: 30311830.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!