The Best Way to Use Antimicrobials for Gut Health, Brain Health, and More

What Antimicrobials Are, and When and How to Use Them

- About Antimicrobials|

- How Antimicrobials Work|

- Antimicrobial Resistance|

- Balanced Approach to Antimicrobials|

- Herbal Antimicrobials|

- Recommended Products|

- Antimicrobials are used to reduce growth of or kill off bacteria, viruses, fungal infections, and parasites. They can be synthetic (made in a lab) or come from different plants and herbs.

- Herbal antimicrobials can help treat a number of infections as well as improve mood, cognition, and decrease common issues such as brain fog, fatigue, SIBO, and stomach distress.

- Antimicrobials can be a helpful next step if symptoms persist after improving gut health with diet and probiotics.

- Use of various herbal antimicrobials can help to eradicate infections, and herbal options often come with fewer side effects than prescription antimicrobials.

If you have been struggling with chronic stomach distress, brain fog, and fatigue, antimicrobials may be able to help. Antimicrobials can help treat many of the root causes of chronic health issues such as SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth), H. pylori, yeast overgrowth, IBS, and IBD. Since they can be used for so many different conditions, it’s important to know the science behind antimicrobials and how they are used.

This article will walk you through what antimicrobials are, what types of conditions they may treat, when they are needed, and a balanced functional medicine perspective on how they may be used in treatment.

What Are Antimicrobials?

An antimicrobial kills or prevents the growth of a living organism [1]. Antimicrobials are commonly used, and you might recognize many of them, such as:

- Antibiotics taken for ear infections such as amoxicillin

- Antivirals like Valtrex for chickenpox

- Antifungals like Lotrimin for Athlete’s Foot

- Disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide and Lysol that kill microbes on surfaces

- Herbal antimicrobials such as oil of oregano and berberine

- Biocides such as pesticides

The wide range of antimicrobial agents can be confusing, so let’s break down the different types of antimicrobials and the microorganisms they target [1]:

- Antibiotics: used for bacteria such as Escherichia coli (E. coli)

- Antivirals: target viruses such as chickenpox or the flu (influenza)

- Antifungals: target funguses such as ringworm or candida

- Antiprotozoals: target parasites such as the parasite that causes malaria

Here’s a quick guide to how each type of antimicrobial works:

Antibiotics (antibacterials): target either the bacterial cell walls, bacterial ribosomes, or bacterial enzymes in order to prevent the bacteria from growing or to kill it off [1]. Some antibiotics target one bacteria, and broad spectrum antibiotics target many different types of bacterial infections at once, such as gram-positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria, or anaerobic bacteria [2]. Some common antibiotics are sulfonamides and penicillin.

Antivirals: work against viruses [3]. Common viruses are the flu (influenza,) hepatitis, and herpes.

Antifungals: target fungi, not all of which are harmful to humans. Some fungal infections cause reactions ranging from mild irritation such as Athlete’s foot to life threatening infections such as cryptococcal meningitis [4].

Antiprotozoals (also called antiparasitics): work against parasites which use their hosts to live and reproduce, which cause infections [5]. Parasites include giardia, tapeworm, fleas, and ticks.

Further, many of these types of antimicrobials treat multiple issues. For example, a common antibiotic, Flagyl, targets bacteria, but also parasites.

Herbal antimicrobials can be used to treat gut infections and overgrowths including SIBO, SIFO (small intestinal fungal overgrowth), and H. pylori, and the stomach distress and fatigue that come with them [6, 7, 8, 9]. They can also be used as part of a treatment plan for IBS and IBD, including both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease [10, 11, 12, 13]. Herbal antimicrobials can be just as effective as pharmaceutical options in some cases, but they often come with fewer side effects [6].

How Do Antimicrobials Work?

Antimicrobials are generally assumed to completely kill off bacteria or fungus. But not all of these microbes need to be completely killed off. For example, a small amount of candida (a type of yeast) may be fine, but an overgrowth of candida can cause symptoms of brain fog, fatigue, irritability, and stomach distress.

Since antimicrobials cover such a wide variety of microorganisms, this chart outlines some of the common issues antimicrobials may be used for and what type of microorganism they are:

| Bacteria | Viruses | Fungi | Protozoa/Parasites |

| SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) H. pylori infection (often found in gastritis) Staphylococcus aureus (staph infection) Escherichia coli (E.coli) Salmonella | Chickenpox and shingles Herpes virus RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) | SIFO (small intestinal fungal overgrowth) Candida overgrowth Athlete’s foot Jock Itch | Giardia infection Malaria Lyme disease |

Benefits of Herbal Antimicrobials

When used right, herbal antimicrobials are extremely beneficial:

- They can help reduce bacterial resistance [14].

- They often have fewer side effects than traditional antibiotics [6].

- They’re easier to use in combination for multiple microbe infections [15].

- They often have additional beneficial effects beyond killing harmful microbes [7, 16, 17, 18].

Let’s look at some of the research behind a few herbal antimicrobials and the conditions they can help treat:

| Condition | Herbal Antimicrobials Used | Supporting Research |

| IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) | Oil of oregano Zataria multiflora Peppermint oil Probiotics | The compounds thymol and carvacrol in oil of oregano and zataria multiflora improved symptoms, with participants experiencing up to a 75% reduction [10]. Peppermint oil has been widely tested and shown to improve motility, reduce inflammation, and improve gut microbiota [19, 20, 21, 22]. Probiotics have been shown to support imbalances in the microbiota and to reduce symptoms of IBS [23, 24]. |

| IBD: Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease | Artemisia absinthium (wormwood, but not sweet wormwood) Curcumin (turmeric) | In colitis and Crohn’s, Artemisia absinthium induced clinical remission [11, 12, 13]. Curcumin is anti-inflammatory and helps maintain remission of colitis [25]. |

| H. pylori infection | Berberine Probiotics | Adding antimicrobial therapy for H. pylori improves the eradication rate, peptic ulcer healing, and reduced side effects compared to regular therapy without berberine [6]. Probiotics have been shown in multiple meta-analyses to improve treatment success for those with H. pylori [26, 27, 28]. |

| Mood and cognitive decline | Berberine Peppermint Oil | Berberine may improve cognition by preventing brain damage associated with dementia and reducing metabolic dysfunction [7]. It has also been shown to reduce depression rates [17]. Peppermint oil has been shown to improve the ability to complete cognitive tasks [24]. |

| SIBO | Berberine Pau D’Arco (Quercetin) Probiotics | When used together, these herbs have been found to be as effective as traditional antibiotics at treating SIBO, particularly in cases where traditional antibiotics have not worked [8, 9]. Probiotics have been shown to reduce bacterial overgrowth and improve symptoms of SIBO [30, 31]. |

A Balanced Approach to Antimicrobial Use

In order to ensure a healthy foundation, prevent antimicrobial resistance, and find the least invasive treatment with the least side effects, we take a sequenced approach to treatment. Instead of starting from an antimicrobial-use-first lens, it’s best to start with resolving gut bacteria imbalances and infections with diet and probiotics. Treatment guidelines for IBS and gastrointestinal conditions from major bodies around the world also support this order of treatment [32, 33].

The first three steps towards improving gut health and overall health should be:

- Reset: Reset your gut with diet and lifestyle changes.

- Support: Support the gut with probiotics.

- Remove: Remove any unwanted gut bacteria, fungi or parasites with antimicrobial herbs.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these steps:

Gut Reset Diet

An anti-inflammatory diet that removes foods that may cause an immune reaction is the first place to start. Not only can this help to reduce symptoms, but the right diet can help to:

- Reduce gut inflammation, which in turn can resolve imbalances in gut bacteria [34, 35].

- Improve symptoms of digestive disorders including IBD [36, 37].

- Reduce the foods that contribute to bacterial overgrowths and improve symptoms of SIBO [30, 38].

I recommend starting with a Paleo diet, which removes inflammatory foods such as gluten, dairy, and legumes. However, if you do not see an improvement, a more restrictive diet may be needed, such as a low-FODMAP diet.

Probiotic Support

Probiotics can help support your gut health by balancing out the gut microbiome.

- One study found probiotics to be more successful than the antibiotic metronidazole in treating SIBO [31].

- Probiotics support a healthy immune response in the gut as well as reduce gut inflammation [39, 40, 41, 42].

- Some research shows that probiotics may help prevent or treat viruses, such as upper respiratory tract infections [43].

Here is a simple guide to adding probiotics into your life:

If the first two steps of reset and support do not resolve symptoms enough and you need to move on to the “remove” step, you can continue to use probiotics in combination with antimicrobials.

This can be beneficial, as it has been shown that:

- Probiotics and antibiotics used together to treat SIBO increased the effectiveness of treatment [31, 44] and, in one study, even doubled the effectiveness [45].

- In treatment for H. pylori, people who took probiotics and antibiotics together had better results than taking only antibiotics [46].

Removing the Bad Bugs with Antimicrobial Therapy

If gut reset and support do not resolve symptoms, we move on to removing any unwanted gut bacteria, fungi or parasites with antimicrobial herbs. In my book Healthy Gut, Healthy You, I discuss how rather than trying to diagnose specific bad microbes that are causing your symptoms, a broad spectrum of herbal antimicrobials may offer better overall results.

Research has also shown that rotating antimicrobial agents including antibiotics can lead to greater symptom relief. For example, rotating antibiotics for SIBO treatment was shown in a 2021 review to lead to greater symptom improvement and better quality of life than taking a single type of antibiotic [47].

Antimicrobial agents may also be used in treatment of non-pathogenic illnesses, such as IBS [48], IBD, and cognitive decline, which may have a contributing root cause of a pathogenic infection and/or inflammation [49].

How to Use Antimicrobials

Antimicrobials may be given on a schedule prescribed by your doctor, sometimes with one large dose, or given in smaller doses over time [1]. Formulations can vary from pill form to liquid.

Depending on the microbes you are dealing with, which could be just one or many, you may be given one targeted antimicrobial [1] or a broad-spectrum antimicrobial that targets multiple pathogens at once.

Herbal antimicrobials are most often taken over a longer period of time (a few months) than traditional antibiotics.

Reducing the Risk of Antimicrobial Resistance

While antimicrobials have changed quality of life and greatly reduced mortality rates from infectious diseases around the world, they have also been overused in public healthcare.

In conventional public health treatment, we are very used to an antibiotics-first approach, which has led to the overuse of antibiotics [1]. This overuse has led to antimicrobial resistance (antibiotic resistance).

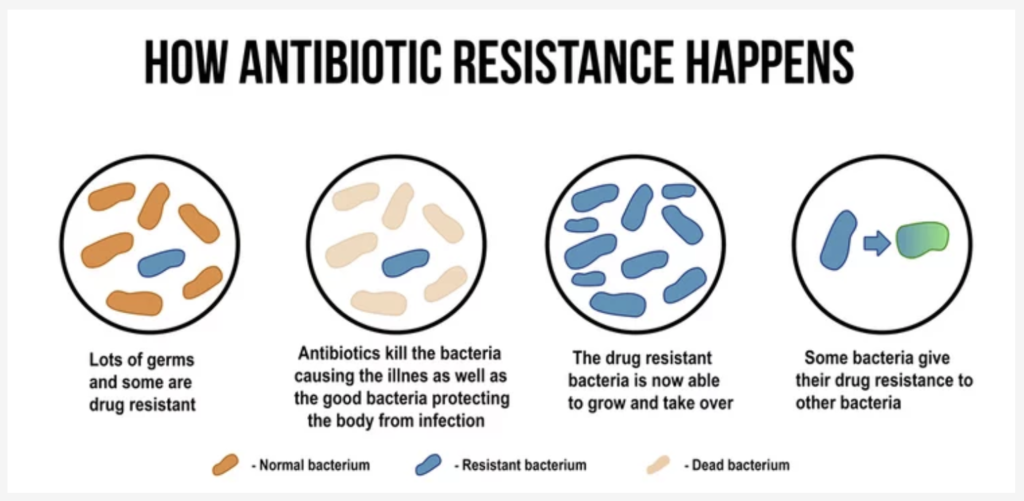

Antimicrobial resistance happens when:

- Microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites) mutate over time so antimicrobials no longer work to kill them off or prevent their growth. This can become a problem, especially when a microbe becomes resistant to multiple different kinds of antimicrobials, like in the case of MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) which can be a particularly dangerous infection in healthcare facilities [1].

- Microbes acquire resistance genes from other bacteria or the environment around them [1].

Putting It All Together

Antimicrobials can be extremely helpful when it comes to gut health, brain health, and more. Remember to start with these two steps:

- Reset the gut with an anti-inflammatory diet

- Support the gut with probiotics

If those two steps still do not resolve symptoms, then we can:

- Remove offending pathogens by adding in a mix of herbal antimicrobials, which we can do safely even if we do not know exactly which microbes may be causing symptoms

With this approach, you can improve symptoms and conditions like fatigue, brain fog, SIBO, IBS, and more. If you need more help figuring out a more personalized treatment plan, apply to become a patient at our clinic.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!