The Carnivore Diet for Gut Health & Autoimmunity

How to approach it safely with Dr. Paul Saladino.

Dr. Michael Ruscio: Hi, everyone. This is Dr. Ruscio. Today, we’ll be talking with Dr. Paul Saladino about The Carnivore Diet. Now, as the name implies, the carnivore diet is a diet where one subsists only on animal products. Not necessarily only animal protein, but also animal fats and organ meats. This diet is one that has risen in popularity of late and I think it’s one that deserves a look.

In the clinic, I have had the opportunity to see some patients who have had very, very sensitive systems that tend to react to almost anything that they eat. Patients self-elected to try the carnivore diet, so I had a chance to just kind of follow along with them, monitor, and see the impact. As I share in this episode, I would say perhaps 60% of patients report quite noticeable benefits from the utilization of the carnivore diet.

We discuss a number of questions relevant to this diet. The history and the research as well as long-term versus short-term use and application of a carnivore diet. We discuss how-tos including time intervals for trying the diet before deciding if it is helpful or not. We also cover what I think are some very helpful techniques to transition yourself to a carnivore diet if you plan to perform a trial – the main problem to safeguard against is having too large of a swing in the amount of carbohydrates that you’re taking in. So if you’re normally eating a somewhat normal carbohydrate intake, let’s say north of 200 grams per day, going to an almost zero intake of carbs may lead to a transition period in which you feel tired and lethargic and just generally unwell.

We cover some traditional techniques to help mitigate this so that you can see the benefit and no real kind of negative adaptations as your body transitions into this mode. We get into a very interesting aside regarding fish and we had a bit of a disagreement in terms of the positions we take on fish intake. This was an interesting volley back and forth and I want to thank Dr. Paul for some of his opinions on this because it’s spawned the idea for me to go into a review of the data on this topic in a closer fashion.

I want to make sure that we are providing you with the best, most up-to-date advice regarding fish intake and how we should be looking at fish and the optimal way to increase fish intake in your diet.

We discussed some other important questions like deficiencies. Does this diet risk deficiencies? Who might the diet be best or worst for? Are there some indications that would tell you this diet would or would not be a good idea? And what is the impact on the gut? Again, in the clinic, I have seen patients who have done quite well with this diet. So there does seem to be something there and I tried to navigate this as openly, but also as cautiously as possible, knowing that any new diet often has a little bit of hysteria that accompanies it. My personal recommendation is to look at this as a type of elimination diet that can be used to the endpoint of healing and eventually, hopefully, allow someone to heal and to be able to tolerate a broader breadth of foods in the long term.

I think Dr. Saladino has a different take in terms of the long term application, and that’s just fine. We both share our rationales, applications, and of course, this is something he’s quite clinically experienced with. So he provides many interesting gems and nuggets of advice in terms of how to apply this diet and how to use this one of many different dietary tools to feel your best. And so, with that, we will now go to the conversation with Dr. Paul Saladino about the carnivore diet.

[Continue reading below]

Episode Intro … 4:59

The History of the Carnivore Diet … 6:08

Improvements While on the Carnivore Diet … 11:21

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Use … 15:43

What about Fiber? … 20:24

The Clean Carnivore Reset … 23:52

Nose to Tail Guidelines … 35:15

Considerations from Hunter-Gatherer Research … 40:03

Risk of Deficiencies … 00:48:29

Contraindications …. 00:52:52

Electrolytes Supplementation … 00:57:37

The Gut Microbiome in a Carnivore Diet … 01:04:31

Episode Wrap Up … 01:18:34

Download this Episode (right click link and ‘Save As’)

Episode Intro

DrMR: Hey everyone, welcome back to Dr. Ruscio radio, I’m Dr. Ruscio. Today I’m here with Dr. Paul Saladino and we’re going to be talking about the carnivore diet. It’s something I get a lot of questions about, something I see a percentage of patients tinkering with. I’ll come back to what I see in the clinic with this. I don’t want to take away too much of Paul’s thunder here. It’s definitely something that’s interesting and I think would be very helpful for people who are very food-reactive and need this extreme dietary reset. This is something I know, Paul, you’re really ensconced in. I’m looking forward to digging into all the details.

Dr. Paul Saladino: Thanks for having me on, man. It’s great to be here.

DrMR: It’s good to have you here. It’s been a while in the making. Your name is the highest recommended on this topic. And I think you’re also telling, with the last name, Saladino.

DrPS: Yeah, man. Are we Paisan?

DrMR: We are Paisan. We’re not going to be talking too much about pasta today, but I guess meatballs would be on the menu.

The History of the Carnivore Diet

In case people have not heard about The Carnivore Diet, tell us a little bit about the history. I don’t even know where this really started. Give us a short synopsis of the history of the carnivore diet.

DrPS: I think most people would attribute the beginnings of the notion of a carnivore diet to this pretty cool arctic explorer named, Vilhjalmur Stefansson. He went to live with the Inuit in Alaska, the northern regions, maybe up in Canadian Yukon territories in the 1920s. What he found there was that people were just living on animals most of the time. There’s not a whole lot of plant food there and so they were living on plant foods very rarely. Essentially for most of the year just eating animal meat and fish meat and organs and animal fat.

When he first encountered this, he thought, “This is crazy. I’m going to get sick. I’m not going to be able to do this.” But it was all he could do, that was the only food that was there and he wrote a number of books about the five to ten years that he spent in the Arctic with these people, including, Fat of the Land, Hunters of the Great White North, and books like that. He details these experiences with the Inuit, what different tribes ate, how they ate it and he details his own health. What he found was profound improvements in health, absence of the development of disease and pretty much he was dumbfounded in how resilient to illness he became. He thought he was going to get really sick and he didn’t so he came back to New York in the late 1920s and was telling everyone about this and saying, “Hey, I just ate “meat”, which consisted of animal fat, animal organs, and animal meat for the last five to seven years on and off, and I didn’t get sick.”

Doctors were like, “You’re full of it, we don’t believe you. You should have gotten scurvy.” So he agreed to go into Belleview Hospital in New York City. He went into Belleview Hospital for a year. He lived at Belleview Hospital for a year under lock and key, cloistered and ate a completely carnivorous diet and there are some amazing papers published about this.

People often will say there are no papers, there are no control studies of a carnivore diet, which isn’t true. There was a paper published in 1930, I believe it was published in The Lancet and it detailed all of their observations and everything that he ate for the year. They looked at blood pressure, weight, mood, and bowel movements and all of the indices they could of his health and they found that at the end of a year of eating a carnivore diet he was completely healthy, pretty darn happy and just a spry dude.

I think people were just taken aback at this. They didn’t know what to make of it. How can you do that? Don’t you need some plants or don’t you need to get Vitamin C from plants or these nutrients in plants? Not only did he not get worse, but he also got a little better and he tended to just get healthier and healthier. The study was filed away and nobody had heard about it for years and years and years, but it’s out there. People can Google it. Only within the last, I would say, maybe three to four years has this idea become popularized again. I think it was a guitarist for the Grateful Dead or the drummer for the Grateful Dead, his name was Bear or something, he wrote a book, Eat Meat, Drink Water and so he was on a carnivore diet in the 1960s and 1970s, just eating meat. It’s had these little instances over time, but in the last three to four years it’s become grown in popularity gradually. I don’t even know where it started three to four years ago.

Certainly in the last year or two has become popularized by Jordan Peterson talking about using a carnivore diet to improve his autoimmune disease, which is probably some variant of autoimmune arthritis. Joe Rogan, as you know, when you get on a big platform like that, people raise their eyebrows, and then his daughter, Mikhaila Peterson, also had significant improvements in her autoimmune disease, which was juvenile rheumatoid arthritis to a severe degree using a carnivore diet. John Baker went on Joe Rogan and then I heard about it about two years ago and I thought, “Man, this is really cool.” I was in my residency at the time at the University of Washington and one of the things that I’ve noticed throughout my medical training, first I was a physician assistant in cardiology years ago then I went back to medical school and then went through residency at the University of Washington and throughout the process, I’ve been thinking, “What is the root of disease? What is the unifying theory here? Where is the singularity? What is causing autoimmune disease?” When I heard this concept that perhaps for many people, plant toxins, plant lectins, oxalates, other things in plants could be triggering our immune system or creating gastrointestinal hyperpermeability as a proximate trigger of these autoimmune processes. I thought, “Isn’t that an interesting hypothesis, let’s experiment with it.”

Key Takeaways

What is the Carnivore diet?

- Consuming only animal meat, organs and fat

History

- Originator – Vilhjalmur Stefansson

- Study of prolonged meat diet 1

- Recent resurgence in popularity by Jordan Peterson and daughter Mikala Peterson who experienced improvements with autoimmune disease

Improvements While on the Carnivore Diet

I started a carnivore diet about a year and a half ago and quickly had improvements in mood, mental clarity, resolution of my own autoimmune disease, which was eczema, that had been kind of nagging for years and years and years and had gotten pretty serious intermittently over the preceding years. I thought, “Man, there’s something to this.” I just dove headfirst into it and since then have been doing everything I could to understand various aspects of the diet and there are many, which we will probably touch on today.

When you tell people that you don’t eat any plants, they have this cognitive dissidence and their brain kind of blows up a little bit and they say, “What about bread?” And you say, “No, I don’t eat bread.” “What about chocolate?” “I don’t eat any chocolate. Look, I don’t eat any plants.” “You just eat meat?” “Well, yeah.” And then I clarify what nose-to-tail carnivore diet means, eating organs and eating fat and eating meat. There are so many preconceived notions or just these sacredly held dogmas that we have in medicine or even in functional medicine that a carnivore diet challenges when we see people improving in health by eliminating plants.

DrMR: I mean, it’s a fantastic occurrence that you saw such improvements. Of course, that makes these things so much more visceral for the clinician when they see their own improvements from it. I’m interested in the carnivore diet because I definitely see this trend where plant matter can be problematic for people. But I also want to be careful to say that I see a trend in the other direction where there are also some patients that do better on what’s known as LOFFLEX or a LOFFLEX-type diet, which is essentially a high-carb, low-fat diet.

I just want to try to keep, and I’m going to keep doing this throughout the episode, because I know people have a tendency, “Oh, it’s new. This is a new best thing for everyone all the time.”, I don’t think it’s quite that simple, but I do think for a subset of people, they do tend to be bothered by vegetables, especially raw vegetables, and FODMAPs can be a problem. They might be intolerant to sulfur or to oxalates or to salicylates and some of these things I see more ring true in the clinic and others I don’t and part of that may be because it’s hard to isolate all these variables, but clearly there seems to be a trend that some people, the food group that bothers them the most, tends to be plants.

DrPS: That’s a big food group.

DrMR: Yeah, I know. Even in my gut-healing. I used to have a problem with spinach. It was one of the foods, why do I feel like this? How can spinach be a problem? So I definitely had some of that, but I also had some meats, eggs, and beef didn’t sit well with me, so I was kind of a mixed bag, but the point I’m driving at is that there are clearly some people who plants bother them, and I’ve had patients who have gone on carnivore diet, and I’ve even recommended it a few times, and I’d say in my observation in the clinic, it’s about 60/40. About 60% of the patients who were helped by it and 40% don’t seem to do well on it. Maybe 70/30 if I’m being really generous. But there is definitely something there, and I think this can be helpful for people.

DrPS: Let’s just pause right there for a moment. You show me the intervention, even if we assume 70/30 or 60/40, how many other interventions do we have in medicine that helps 60% or 70% of people?

DrMR: Yeah, sure.

DrPS: That is a profoundly impactful thing and part of why I’m writing my book, which is called, The Carnivore Code. It’s coming out in a few months. Is to help that extra 30 to 40% that don’t seem to do well on it in the beginning. There’s a lot of nuance there, right? As you and I can talk about, I think there are some people who do a carnivore diet and have underlying overgrowth or the wrong type of microbes in their gut, they have C-Diff or they have something that a simple dietary change isn’t going to fix. I’ve seen C-Diff persist after a carnivore diet, for instance. But think of the number of interventions. We can probably count this on one hand in medicine that can help 60 to 70% of people. That’s unreal.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Use

DrMR: Agreed. And then that’s why I think getting the diet right is such a crucial aspect because that’s the foundation and diet, sleep and exercise. You’re going to see so much more improvement if you can get those dialed in. So agreed, yeah. I don’t want to diminish the potential effectiveness of the carnivore diet, but I’m just going to always be careful to play the devil’s advocate here just because I see how quickly people run off the rails with something new and so I’m going to try to keep providing at least a little bit of counterbalance. This does lead to one question. And again, I want to get to the nuance of how to effectively execute in a moment, but one question that comes up oftentimes is short-term versus long-term and at least in my perspective, not being an expert at all in carnivore, but I view this as an extreme elimination diet that hopefully will allow some healing to occur and want to be able to move to a broader diet over time. Do you share that? Would you modify that at all?

DrPS: I think it depends on the individual and their goals. There are now thousands and thousands of people doing carnivore long term. I, throughout all of my research, explorations, have not found any reason that the human organism can not do carnivore long term. In terms of medical disqualifications or I should say biochemical, metabolic disqualifications, it appears to me, just like Vilhjalmur Stefansson, and the name of that study is, Prolonged Meat Diets with a Study of Kidney Function, Ketosis. People can look it up, it’s all open source.

The Inuit and many other cultures who lived primarily on meat-based diets or animal-based diets. Humans can do this long term, there’s no evidence that I have seen yet, and I want to remain open too. As excited as I am about sharing the nuance of this diet and sharing the idea of this diet with people, I also appreciate your perspective and want to remain somewhat open to the fact that there could be issues, but I haven’t found any yet.

I don’t think there’s any reason that people cannot physiologically, biochemically do a carnivore diet long term and maintain excellent human health and we can talk about all of the potential questions people may have about that, but if someone’s goal is to use a diet and then reintroduce previous foods, I think that’s another use of it as well. That’s totally valid. In that case, we might consider it as an elimination diet, a very powerful, robust elimination diet. I might frame it a little differently than an extreme elimination diet. I would call it more of a “prescription strength” elimination diet or a “robust” elimination diet.

But I think that that’s a very powerful use of it as well and I do not believe that it’s just limited to that. I think that people can thrive on this long-term. But the conversation that I always have with my clients or people with questions is, what are you concerned about? Why would you want to introduce plants again? Some people say, well I like the variety. And I say, that’s totally legitimate. I like the color or it’s a social thing, those are all completely valid reasons to want to include plants in our diet. If people say, nutritive value or lack of a nutrient, then we start to have that conversation and say, “Well, I’m not aware of any, I don’t think you need plants for that.” So I can belay those fears for people. But I’m good friends with Ben Greenfield and his wife, Tessa, makes amazing meals and they have all sorts of color and I think that he enjoys having food on his plate beyond animal food just for variety and that’s legitimate and I think, as you are suggesting, the reintroduction of food can be within the framework of, do your symptoms reoccur.

And if somebody does a carnivore diet and has improvement in symptoms and then they can reintroduce foods without recurrence of symptoms, then that’s amazing. But it can also be useful and viable long-term.

DrMR: I see the potential for viability in the long-term. We, of course, I think need some better data where we track a cohort of people for a couple of years and see if any issues pop up, but in absence of the evidence, because I don’t believe we have any of that evidence other than the originator’s diet, which, that’s a data point, so we should definitely consider that. There are some other inferential data points we can look to. Mat Lalonde had a great presentation at AHS a number of years ago and he went through, what I believe was described as a Ph.D. thesis-level of research to do an independent analysis of nutrient density in different foodstuffs and found that meats and organ meats were the most nutrient-dense and most nutrient complete by far.

DrPS: I couldn’t agree more.

Key Takeaways

Long term/Short term?

- Paul feels there is no problem with sticking to the diet long term

- Can be used as a short term elimination diet to reduce inflammation, figure out if plant foods might be causing issues, etc.

- Interesting presentation/reference about the nutrient density of meat – Mat Lalonde AHS presentation

What About Fiber?

DrMR: That’s one data point and then I was going through the research for Healthy Gut, Healthy You, one of the things that was the most difficult part of the research but also the most enlightening, was taking an honest look at fiber in the diet and health and morbidity, mortality and there’s no consistent trend showing that those who eat more fiber are healthier, especially when you control for founding variables like people who eat less fiber are more prone to eat sugar and trans fat and smoke. When you control for those confounders, we can’t really say that those who eat more fiber are healthier. I do think there are some inferences that support the fact that we may not really need plants. Now I know that sounds like a strong statement, but if we come to a patient group who feel sick every time that they eat, this is where I think it’s the most tenable. Okay, what do we do for this person whose skin is always inflamed or their joints are always in pain or they always have this food-reactive brain fog, or gastrointestinal symptoms?

I think, at the very least, if you wanted to be a doctor who is the most parsimonious with how they allocated dietary recommendations, at least for this subset of people, I think it’s worth an experiment. I think you’ll find, as I have found, that there are definitely patients who will say, “I feel the best on carnivore that I have felt on any diet.” That’s a powerful piece of evidence that really needs to be incorporated into our conversation here.

DrPS: Yeah, I think it needs to be in every clinician’s toolbox. There are a lot of roadblocks to that. You mentioned a few of them there, but yeah, in terms of micronutrient density and bio-availability, animal foods are unparalleled. We can go into the details there if you’d like, but on my podcast, which is Fundamental Health, I’ve had a conversation with Chris Masterjohn about nutrients and we have this ongoing discussion about the nutrient adequacy of a nose-to-tail carnivore diet and it certainly looks like, at least within the framework of what we know about nutrition, the RDAs may be different and perhaps are not the best measures, but even looking at the RDAs, we really can get basically everything we need to thrive as a human in terms of vitamins and minerals at an objective level eating animals nose-to-tail.

You make a great point about the fiber. The fiber conversation is fascinating and it is a deep many-tunneled rabbit hole and the end result of that conversation in all of the discussions that I have had with numerous people and through my own research has been, “Hey look, humans do not appear to need plant fiber for optimal health.” And we can talk about the microbiome if you want or short-chain fatty acids, but all of those conversations … they just end up in the space of like, “Hey, it doesn’t look like we need plant fiber for this. So it’s an extremely viable option.” How cool would it be if every functional medicine provider in two or three years felt comfortable saying, “Hey, you know what, we did Paleo, let’s go the next step. Let’s do carnivore or let’s use a carnivore diet as an adjunctive tool.” That’s my goal. To equip medical providers with this tool and then empower people in the space who may not even be sick enough to investigate this as enough adjunct in their life to improve their quality.

The Clean Carnivore Reset

DrMR: I see the easiest way to get buy-in from providers who might be a bit, I don’t know, for lack of a better word, skeptical or really kind of cautious is thinking about this as elimination followed by a reintroduction because then you’re at least not taking the position that you have to do this forever. I’m not saying that’s the best approach, but I think that might be the approach that gets people to, okay, lets at least run the trial for a few weeks, see if you feel better and then we can try to reintroduce to tolerance.

How do you feel about that way of framing this?

DrPS: I think it’s fine. I frame it that way for a lot of my clients too, because what we know about humans is that if I said to you or anyone, “Hey, you’re going to just eat meat for the rest of your life.”, people are like, “What do you mean?”

DrMR: Forever is hard.

DrPS: Forever is hard. But what about for the next 30 days? In the book, I talk about the clean carnivore reset and it’s just 30 or 60 days. That’s a reasonable time frame for the immune system to reset and become a little more quiescent if you’re removing the actual food triggers. It’s a little bit of time for people to see how they feel. Now four to five days, probably not enough time, 30 to 60 days, a pretty good amount of time to see how people are doing and at the end of that, they can say, “Hey, let’s do another 30 days or let’s reintroduce.” That’s fine and reintroduction can be gradual and very careful and sometimes people find that they feel best without the plants.

I have a lot of clients who have trouble giving up coffee, which is one of the most sacred cows, I think, in the westernized world. I’ll say, “Hey, let’s just think about …”. I frame it that way, I don’t say forever. I just say, “Hey, let’s think about this for 30 days or even 15 days.” Then they reintroduce it and they go, “You know, I was so shaky.” Obviously this is an adjustment back from the tachyphylaxis with caffeine, but they realize how much more sensitive they are to those things and other foods. When people reintroduce foods, as you know, they can have a much better sense of the way it’s affecting them than when it’s in this mixed chaotic environment with too many variables, and I think that’s what is so powerful about elimination diets of all kinds.

DrMR: You brought up the concept of adaptation time and this is something I really would like to hone in on. I try to provide people with a guideline. Go on a dietary trial for X amount of time and if you’re not noticing improvements by X, then this may not be the best diet for you and for most diets, in my experience, you start getting an indication at two weeks and usually by four you should either be able to say, yes I’m feeling better or I don’t feel any different or maybe I even feel worse. Would you say that the carnivore follows the same kind of trajectory?

DrPS: Yeah, that’s been my experience. I interviewed a gentleman named Brett Lloyd on my YouTube channel a while ago. He had debilitating depression his whole life, and when he went carnivore, he said he just woke up on day 28 and was like, “Whoa, something is different.” It was like a switch had flipped, but it took four weeks. And then the immune system flipped. When I interviewed Mikhaila Peterson on my podcast she said that she had, I think she had four to five months before her depression started to lift, but I do think she started to feel some improvements around a month. So I think that if people are doing some dietary intervention, whether it’s Keto, Paleo, AIP, carnivore, I do think they should get some indication of what trajectory it’s having within like four weeks. And then you could go from there.

You may not see the full benefits at four weeks and certainly, we know that for a lot of people who do a carnivore diet, or any sort of low carbohydrate diet where they are shifting their metabolism over to a fat-based metabolism or Ketogenic metabolism, the athletic adaptation is going to take much longer than that, but in terms of symptomatic improvement, I think generally you should see some movement within four weeks.

DrMR: Now what are you typically seeing in the first week or two? Oftentimes when people go on Paleo and after the first week they are losing a little bit of weight, they are feeling a little bit better. Does this diet take longer to switch into that “I’m feeling better” phase?

DrPS: It depends on what they’ve done before. A carnivore diet by its nature is going to be ketogenic. There’s a small amount of glycogen and muscle meat, but people are going to get very, very low carbohydrate diets. If somebody has, and there are ways to modify that as well, and we can talk about that, but for most people who start a carnivore diet, if they’ve never done a ketogenic-type diet, they are going to go through keto-adaptation, which can be a little rough for people just in terms of the biochemical machinery that has to happen, differential transcription at the molecular level and I’m sure we could go down this rabbit hole with Anthony Gustin some time, but the ketogenic transition can be a little rough and people can get keto-flu, which they might want to think about electrolytes or et cetera, et cetera.

The first week of a carnivore diet can be a little bumpy for people and one of the things that I do observe is that when people change their diet away from plant-based carbohydrates, there’s a shift in the gut flora for sure. And there’s probably a shift in bile-acid production, bile-salt production, overall bile production because they are eating now meat and fat, protein and fat. So those two things combined can cause some GI symptoms, a lot of people, I’d say a moderate number of people get loose stools in the beginning. That usually resolves within a few days. Some people never get it, but I think there is a real shift in the gut microbiome, people can feel that. There can be a shift in the amount of bile being produced and the small intestine has to up-regulate its ability to reabsorb that and recycle that.

I think for people going to a carnivore diet, if they have come from a low-carb paleo diet, they’ll be better off and they might have a smooth transition, but if somebody is doing a standard diet or a very high carbohydrate diet and they try and go directly into carnivore, the first week might be a little rough and I think it’s this transition.

DrMR: So do you think it would be a viable strategy to try to mitigate this. Let’s say someone’s going, “I can’t go through a week of feeling tired because of work or whatever”, ease them in with some intermittent fasting and some lower carb dieting. Let them kind of have a transition period there and then after they feel adapted to that, go to a full-blown carnivore?

DrPS: Yeah. The other thing you can do is use things like honey or you could do a carnivore-ish diet, which I say tongue in cheek, but I talk about that in the book. I think there is a spectrum of plant toxicity and it depends on what we’re targeting. But if somebody wanted to transition into carnivore but didn’t want to be ketogenic, you could do a predominately animal-based diet with maybe some squash. Think about a low lectin, not using the seeds or the skin of the squash obviously, like a low lectin, low oxalate carbohydrate like squash or a little bit of cucumber or you could use honey to affect the metabolic machinery in a different way so you’re not doing both at the same time.

You’re not going to go into ketosis, but you’re going to eliminate 99% of the plant foods you’re eating and then if you want to get rid of that last one, you can go into the ketogenic transition gradually. But also, I think as you’re suggesting, intermittent fasting, gradually lowering the carbohydrates is a good idea. I know Peter Itea talks about not going from a high carbohydrate diet to a five-day fast. He’ll often do a week of a ketogenic diet in between so that that transition is much easier. I think something like that might be used as a run-up.

DrMR: Yeah. Well, whatever you can do to mitigate that low-carb flu, feeling fatigued, because … I mean, it’s great if you can push through that and if you’re mentally strong enough or your life isn’t demanding enough where you can get through that, but I know so many people just don’t, they don’t have that luxury. They’ve got to be a mom, a dad, a boss, a worker, what have you.

DrPS: I think the only thing I’d add to that is that for most people it’s worth it. There’s something valuable on the other side. It’s not just like you’re suffering unnecessarily. But yes, I think that that sort of a transition would have happened for us evolutionarily much earlier in our life. We can basically go now from the time we first have foods at one-year-old or six months or eight months and never be carb deficient. I shouldn’t say carb deficient, we can never have a carbohydrate-free day for 30, 40, 50 years and that I think is an evolutionarily inconsistent situation. Most of us would have gone through something like that in childhood very quickly.

You know, kids go into ketosis between meals even if they are eating a mostly carbohydrate or a carbohydrate-rich diet in general, but as we age we tend away from that carbohydrate, from that ketogenic proclivity between meals. Before I experimented with this and ketogenic diets, I had carbs every day for 30 years. There was no question. Most people, most of our ancestors evolutionarily would have had a winter or a season where they had become “keto adapted” and I think once we’ve done that and we’ve developed this new molecular engine and we can burn fat or we can burn glucose, then we’re good to go. Most of us just haven’t done that. And so if people are hesitant to go through that process of keto-flu or keto transition, I would just say, “Hey, you are basically building a new engine in your car. You are going to be bigger, better, faster, stronger. It’s going to take a little work, but it’s worth it.”

Key Takeaways

How to do it?

- Initial evaluation period of 2-4 weeks

- The more keto-adapted you are the sooner you will feel better

- Might want to ease into this with fasting and lower carb dieting

- Might feel worse at first as you adapt

- Athletic adaptation can take longer

Sponsored Resources

DrMR: I’d like to thank Transcend Labs for making this podcast possible. As per our last interview with Dr. Alex Capano, who has her Ph.D. in cannabinoid research, the best evidence for CBD is regarding the treatment of pain, sleep, and mood conditions like anxiety. You have to be very wary of cure-all health claims. You also have to be cognizant of quality assurance, and this is why I’m happy to say that Transcend Labs pays close attention to this.

They use full-spectrum CBD across all of their products. In fact, they have pretty delicious gummies that I’ve sampled a number of times. They use third party analysis, verifying the safety and potency of all of their products. They use a minimal dosage of 25 milligrams per serving across all products, making it easy to switch from an edible to an oil. You don’t have to do all these dosage conversions. You’re going to have consistency of dosage across products, and they only use the most effective CBD delivery systems, such as oil, edibles and topical creams.

You can receive 20% off all Transcend Lab CBD products if you visit transcendlabs.com and use the code RUSCIO20 at checkout.

Nose to Tail Guidelines

DrMR: You mention nose-to-tail and I don’t necessarily want to go into all the exhaustive details of how to execute the diet, but what are some broad strokes for people. Obviously you want to just not have steak every day, you want to try to eat nose-to-tail as you alluded to, but what are some key points and mishaps to try to avoid?

DrPS: So the two biggest things I would say are, thinking about the fat-to-protein ratio and the inclusion of organ meats. I think everybody is going to be a little different in terms of what their body is amenable to in terms of fat-to-protein ratio. If you and I are going to go out hunting and we’re going to respectfully stalk an animal and be thankful for the sacrifice it’s made as we kill it and eat it, we’re not just going to eat the muscle meat, we’re going to eat the whole thing. We’re going to eat the connective tissues, we’re going to eat the fat, we’re going to eat all the organs. I think that’s the way we should mirror this in our diets, whether we’re including plants or not. Even if we’re not on a carnivore diet, I think it’s important to get our organ meats in our diet, most of us just eat steaks.

But the first thing we think about is, are people just eating lean meat, that’s a recipe for failure. There are plenty of historical accounts of “rabbit starvation” in arctic explorers. Lean animals, without fat, are not suitable for exclusive human nutrition. Our metabolism doesn’t work with just protein. There’s an upper limit to the amount of protein we can metabolize through the urea cycle based on our genetics. But for most people, it’s not low, but it’s around 250, 300, 350 depending on how big a person you are, grams of protein per day. We don’t just want to eat protein for energy, we’ll end up overwhelming the urea cycle, spilling ammonia and not feeling good and that’s what rabbit starving basically is. It’s over-consumption of lean meats at the exclusion of carbohydrates and fat.

Our bodies need one of those other two macronutrients to thrive. You can eat carbohydrates or fat and people can decide which one they prefer or they can use both, but if we’re going the ketogenic route, we’re sort of swaying toward the “fat-burning” and in that case, the ratio between fat and protein is important to consider.

Most people, unless they are eating the leanest cuts of steak exclusively, will get enough fat in their diet to do just fine, but some people feel better with a little more fat. Some people feel better with a little less fat. Generally speaking, about 70% of your calories from fat and 30% of your calories from protein is where most people kind of end up. That’s where Vilhjalmur Stefansson ended up essentially during his Belleview experiment. That’s basically where we trend. Some people like higher fats, some people like a little more protein, but we just have to remember that protein is four calories per gram, fat is nine calories per gram, so you can do the calculations of what the actual gram percentages of the protein and the fat would be for different people.

If people are eating some fatty meat, they will get enough fat in their diet. The concern is just that they would get too little fat and feel horrible. If people are just eating hamburgers, you’re going to feel miserable. And then the second thing is that muscle meat, though it’s extremely nutritious, doesn’t have a full complement of vitamins and minerals. It’s pretty good, but as soon as we start eating the rest of the animal, things really come together nicely. The one organ that a lot of people start with is liver. In a lot of traditional cultures, liver is sacred, it’s passed around the tribe, eaten raw and it’s just totally treasured by the people because they are quite aware of the unique nutritional value of liver. What we know today is that there are a number of B vitamins and vitamin A that are uniquely contained in liver and not present in the muscle meat, specifically things like folate, riboflavin, biotin. They are much higher in liver, liver also is a good source of copper to complement the zinc in muscle meat, things like this.

Liver is a unique organ and the other organs are all kind of similar in that sense. Kidney is also quite nutritious, but if people are doing a carnivore diet, the inclusion of at least liver, perhaps liver, kidney in their diet will make it much more nutritionally complete and they will do better long term. If you consider that, with the protein-to-fat ratio, people usually do just fine and then we can think about whether someone is sensitive to eggs, if they are getting egg yolks, that helps. If they are sensitive, we can avoid them. Obviously there are a few other considerations. If they are sensitive to seafood, or histamine sensitive, we need to think about where they are getting their iodine, things like that. But basically, the most basic version of a carnivore diet that I think people will be nutritionally full or nutritionally complete on is fatty meat and some organ meats plus or minus eggs or seafood.

Key Takeaways

Dietary guidelines

- Fat to protein ratio: Don’t avoid fatty meat, 70% fat, 30% protein roughly

- Eat nose to tail: Eat more than muscle meat; liver, kidney, eggs

- Get ample electrolytes – especially at the start of a Carnivore diet; 1500-2000 of sodium

Considerations from Hunter-Gatherer Research

DrMR: One of the things I always wonder about is Cordain published a paper a number of years ago essentially looking at the macronutrients of hunter-gatherers worldwide and one of the points from his paper that always struck me was, as he moved from his assessment at the equator, north and south, to the colder regions, the poles, the main foodstuff in the diet that increased … As carbs go down, we know it as we go away from the equator, there are fewer carbs in the indigenous diet. Fish was the main food brought back in. But it seems, at least from what I’m capturing here, that that doesn’t seem to be so much reflected in the carnivore diet. Is that correct? Did I miss something? And if I am correct, how do you speak to the distance with the Cordain findings?

DrPS: Cordain’s findings are interesting, but unfortunately reflective of populations of hunter-gatherers that are influenced by current sociopolitical norms. The populations that he was studying in the 80s and 90s are affected by legality, land use, they can’t hunt elephants anymore. They can’t live the way that traditional hunter-gatherers probably would have. I did a podcast with a paleontologist and we talked a lot about this. We know that the Hadza, for instance, and the Ye’kuana, they can’t do their normal traditional way of hunting now because they are not allowed to kill elephants or large game so they are forced to hunt small game, which means they have less fat on the animals and they have to rely more on plant-based carbohydrates.

One of the more compelling hypotheses I’ve heard with regard to, or at least counterarguments, recordings, findings with regard to macronutrient ratios of hunter-gatherers is that what we see today is probably not reflective of what happened previously. In the conversation I had with Chris Masterjohn on the podcast, we even got into this. That when the Hadza are able to get a large animal, they will just eat that animal exclusively for two weeks and really won’t do much gathering of plants because they don’t need to. They have all of the foods they need there.

As you move away from the equator, you’re suggesting that people increase their consumption of fish, is that what you’re referring to?

DrMR: That’s what Cordain found in his paper.

DrPS: The problem I have with the high consumption of fish now is that it’s almost a certain recipe for heavy metal toxicity. Tony Robbins is an example of that, unfortunately. I think that-

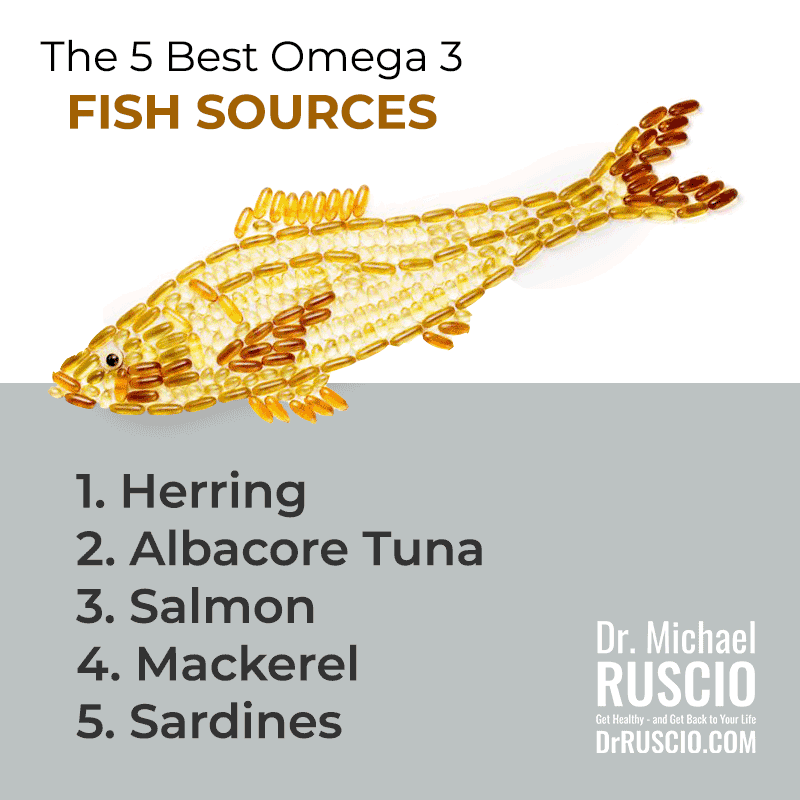

DrMR: That’s been debunked as long as one’s not eating fish that are known to be bio-accumulators. So as long as one is avoiding shark and whale, and this is something known as a selenium health benefit index. I think it’s really important that we draw that distinction and there was even one paper looking at pregnant mothers who avoided fish, actually had poor neurological outcomes in their children. With the one caveat exception that we are not eating mainly shark and whale.

DrPS: I don’t think Tony was eating shark and whale, man. I think he was eating a lot of tuna. I think tuna is pretty high.

DrMR: I’d have to check where tuna falls, certainly there’s more on the list of bio-accumulators, but things like salmon, sardines, many of the oily fish that get lumped in with this, I think people avoiding those unnecessarily causes problems as this one study looking at neurological outcomes in mothers showed. I’ll put a link to this in the podcast for people because we did do a review on this a while back. You bring up a good point, which is, we should be clear in terms of what fish to avoid and what fish to not to avoid, just not castigate all fish is bad.

DrPS: No, I’m not doing that, but I will tell you that clinically I have seen even in people who are eating wild Alaskan salmon multiple times a week, elevated whole blood mercury and metals. I’ve seen mercury at five or six in people who are eating salmon a few times a week. I think that this is more of a problem than we care to admit to tell you the truth. I’m not saying don’t eat any seafood, and I certainly eat seafood from time to time, but no matter what seafood we choose to eat, I would suggest that seafood has now become much more polluted than land animals just because of what we’ve done to the earth and the bio-accumulation of metals within the oceans. Having a primarily pescatarian diet, I think is a tenuous place to be without careful monitoring of metals in our blood. In today’s day and age, this is almost like an apocalyptic type thing, but this is what we see.

You go to the grocery store and the majority of the fish you see there is moderately or highly contaminated with mercury. You might find some salmon that’s okay. Maybe some smaller fish, but … You know, halibut, king mackerel, sea bass, opah, it’s all quite high in metals and people, if they want to include that in a diet, should be careful.

If we’re talking about omega-3s, presumably that’s what’s going on for these pregnant mothers. There are plenty of good sources of omega-3 in animal food other than fish. My talk at Ancestral Health Symposium was on the value of animal fat and grass-fed animal fat is a great source of EPA, DHA, and DPA. If we’re thinking about seafood sources of that, salmon roe is a great option because it’s a phospholipid form of DHA and salmon roe is going to be much lower in the metals than the actual flesh of the salmon. But then you could also include shellfish if you wanted. Things like oysters, I think these are valuable parts of the diet, but yeah, I think there needs to be some caution about over-consumption of fish in general. I think it’s not as benign as many would suggest.

DrMR: You raise an interesting point and you’ve inspired me to actually circle back to this issue. One of the things I’m going to do in light of this, is to do a little additional digging into the research. It’d be great if we could find a large cohort of people who are following a pescatarian diet controlled for confounding variables and see if there are any health issues with them and then revisit some of the selenium health index benefit paper findings.

More to follow, everyone. I definitely want to make sure that I’m not giving or absolving fish of any culpability that it may have. So I’m going to revisit that because I think it’s a great question and one that I think is worth circling back to and looking at more thoroughly.

DrPS: I had a client who ate sea bass for, I think she had a big piece of sea bass that she got and she had a bunch of it and then did a NutrEval and her mercury was 24 or 25. It was astronomical.

DrMR: I’m also wary of some of the functional medicine tests because some of these tests have set their own lab norms.

DrPS: This is not a provoked urine, this is just a whole blood mercury. Kind of the standard. This is a whole blood mercury on the NutrEval. I’m not using VMSA, not provoked or anything like that. Just a normal test. That’s above the reference range even for normal toxicology.

DrMR: I think it’s interesting so I’m definitely going to dig back into this and we’ll, for our audience, look into this issue, research a little bit more and try to post an updated conclusion because I want to make sure we’re giving people the best advice and I want to make sure that the most recent review, I’m not sure if you’d caught wind of this, maybe five years ago now, there were a couple of researchers making the rounds with analysis they did looking at fish more discriminately and finding that if there the appropriate balance of selenium along with the mercury, there was really no risk of mercury toxicity. But it’s worthwhile double checking that.

DrPS: Yeah, yeah. I think that’s an interesting possibility and I think that eating a selenium-rich diet, like a meat-based diet might be protective against that. But you’re familiar with Tony Robbins’ history. I think he was pretty bad in the past after his pescatarian diet. Again, it’s just one person that I’ve heard of.

DrMR: More to follow there, and Paul, of course, I’ll loop you in on what we find.

DrPS: Please do.

Key Takeaways

Does the carnivore diet include fish?

- If you are to include a bit of seafood, best to stick with species that are known to have less mercury like oily fish

- Wild caught salmon

- Sardines

Risk of Deficiencies

DrMR: So we talked about deficiencies and I want to ask a question again in terms of what is the risk of deficiencies and are there any. I know we can draw an inference from looking at the combination of nutrient-dense foods, and I think we’ve already established that a well-procured nose-to-tail diet doesn’t seem to suggest a high risk of deficiency.

Do we have any more compelling data in terms of a group of people besides the founder who was tracked? Anything more there in terms of outcome measures that we could look to?

DrPS: Other than my cohort of patients and my personal data and the data of citizen scientists doing the Carnivore Diet, those are probably the best things right now.

DrMR: What do we have there? Roughly what kind of sample, what kind of time period?

DrPS: I’ve been seeing patients and using a Carnivore Diet for over a year now in my practice. I’ve been on the diet for a year and a half and as a practitioner, I’m pretty ridiculous about this myself. I’ve tested myself multiple times. There are all these clinical correlates of nutrient deficiencies and we don’t really see any of them. I think the thing that I see more often than not is a homocysteine going up because people aren’t getting enough riboflavin because they are not eating enough organ meats. This is going to be more common in people that have MTHFR polymorphisms. I think if we look at the nutritional levels of people who are eating primarily meat-based Carnivore Diets, it is more common to see mid-range of flood levels of folate—depending on how accurate we think that is—as an indicator of folate status. If you’re going to do an oat test, you might see markers of folate status on there too, if you’re looking at FIGLU or something like that.

But generally speaking, in what I’ve seen, people do not get nutrient deficiencies on this diet. I think that, as we’ve eluded to when you think of animal meat and animal organs as the most nutrient-dense foods, the more of those you include, the better you’re doing than the general population.

Even within the general population, nutrient deficiencies—though more common than we believe—are not incredibly common causes of major pathology, though some may argue with that. The labs that I would check would be obviously a B12, serum folate, B6. You could look at vitamin C levels, you could look at markers of inflammation. You could look at markers of oxidative stress, lipid peroxides, things like that. You could look at full levels of glutathione and then you could look at red blood cell levels of things like selenium, magnesium, potassium. You can look at whole blood zinc, you can look at manganese, and what I generally have seen in my cohort of probably, I would say, 100 plus people, 150 people, is the nutritional deficiencies don’t show up and we would not expect them to.

I think it’s more common for people to get nutrient deficiencies when they are eating plants as a portion of their diet because plants are replacing the most nutrient-rich foods. Plants also have anti-nutrients, which can impair the absorption of minerals, at least divalent minerals like calcium, magnesium, zinc, selenium, oxalic acid, and oxalates. From a personal perspective, what I’ve seen and what others in this space have seen is that people don’t develop these deficiencies, not from a laboratory perspective or from a clinical perspective. That’s eating the organ meats, however.

DrMR: Sure. I was going to say the organ meats tend to be pretty potent in B vitamins. Iodine comes to mind, and I guess eggs would be probably your main way of getting in the iodine.

DrPS: Yeah. I recommend my clients include some seafood, just not making the majority of their diet seafood. There is a decent amount of iodine in egg yolks, and you can get plenty of iodine with some servings of seafood throughout the week, you’ll get some iodine.

Key Takeaways

Deficiencies?

- Paul has only seen:

- Potentially higher homocysteine due to lower riboflavin intake

- Folate lower normal

- Usually due to not eating enough organ meat

Contraindications

DrMR: Another question I wanted to ask, is there any clinical indication you’ve been able to tell that could predict who would do better or worse with a Carnivore Diet? And I’m just putting my clinician hat on for a minute if there is any way I can preemptively or at least suggest this diet may not go well in this patient so I’m going to try to go to other diets first? Have you teased out any indicator there?

DrPS: There is this very rare polymorphism called CPT1A and it has to do with carnitine palmitoyltransferase. What’s interesting is that that polymorphism occurs in the Inuit people. That would be the one I would think of, but that’s in the population of people that are probably eating nothing that’s close to this. Even that alone would not be an apparent contraindication. That polymorphism makes it difficult to generate high levels of ketones because your body can’t shut all the fatty acids into the mitochondria for beta-oxidation. If you look at the majority of the Inuit, they don’t have incredibly high levels of ketones. There are numerous theories about why that polymorphism became favored in that population.

I think that it’s not something I’ve been able to predict. The majority of people that I work with do really well on this diet and there have not been many people who have not done well. I think that when people have trouble with it there is often something to troubleshoot: Whether it’s not enough fat or not enough organ meats, or the electrolytes are a bit off, or there is something preexisting in the gut. There’s no patient that I can think of, population-wise, that comes to mind to think that person’s not going to do well with a Carnivore Diet. I think that we’re still learning here and any clinical observations that you have of patients not doing well I’d be open to.

Key Takeaways

Who is it best/worst for?

- Best: Those who feel better on lower carb and keto type diet

- Worst: No predictor, Dr. Paul feels it helps most

- Heart disease: Carnivore diet is OK

The questions I get are the following:

Can I Do a Carnivore Diet with Gallstones?

Absolutely yes. One of the reasons people get gallstones is because of a choline deficiency. We know that choline is needed by the liver to transfer bile salts from the hepatic sinusoids into the biocanoliculi. In a choline-deficient state where the bile is bile-salt deficient, the cholesterol concentration is too high and precipitates as cholesterol stones. A lot of people with gallstones are not getting enough choline. What are the sources of choline? Animal foods. Someone with gallstones could certainly do a Carnivore Diet and that the increased choline would be helpful.

Can I do a carnivore diet if I have chronic kidney disease

Every once in a while someone asks, can I do a Carnivore Diet if I have chronic kidney disease? That might be the one situation where it’s like, “Well if you want to increase the amount of protein in your diet, I don’t think we know what happens.” There is certainly no evidence that moderate or higher protein diets impair kidney function, and there is some evidence that they may improve kidney function. However, it has not been studied well in chronic kidney disease populations. If somebody had preexisting chronic kidney disease, I would be careful and watch their markers of kidney function as they embark on the diet.

Can I do a carnivore diet with heart disease

The last population that people sometimes ask about is, can I do a carnivore diet with heart disease, and to that, I would say, resoundingly yes because meat and animal foods do not cause the production of heart disease, in my strong opinion, nor is LDL the main atherogenic molecule in the human body. People will say, “Oh, I’ve heard the carnivore diet can raise LDL, and often ketogenic and carnivore diets do raise LDL, but as I’ve enumerated multiple times on previous podcasts, and I go into in much detail in the book, the evidence that LDL is the main driver of atherosclerosis or is uniquely atherogenic on its own, I think is severely lacking and so what usually happens when people do a carnivore diet from a lipid perspective, is they become much more insulin sensitive and they have a better-looking lipid panel in terms of HDL/triglyceride ratios and fasting insulin, other inflammatory markers usually go down.

Sometimes mainstream docs get a little bit worried when HDL goes up, but I think that if we sort of reframe, I think the whole LDL, that’s a whole other separate podcast, but the whole framing around atherosclerosis is driven by LDL is quite wrong in my opinion. That’s kind of a rambling answer to your question.

DrMR: I’m in agreement with you there that it’s important to look at the total picture is one thing I think Christopher Gardner at Stanford did a great job pointing out in his A to Z Weight Loss Trial where LDL went up in the lower-carb group, but so did HDL while triglycerides went down, blood sugar went down. Blood pressure often went down. So when you look at the total risk profile, we shouldn’t just fixate on LDL alone and look at the aggregate findings.

Electrolytes Supplementation

You also mentioned electrolytes and I think that’s just worth underscoring because that is something that I’ve seen. I am thankful for speaking at a keto conference last year, this was brought to my attention, that was echoed by Robb Wolf and I’ve now been using some of Robb Wolf’s LMNT electrolyte in the clinic and it’s definitely helping some people who are low carb and I haven’t gotten the download that you may need to be supplementing with electrolytes if you’re not salting your food regularly. But do you have any more definitive guidelines for the electrolyte piece?

DrPS: This is quite interesting because I’m going to record a podcast with Robb tomorrow and we’ll hobnob about this a little bit, but this is what we know, that in a state of let’s just say carbohydrate driven metabolism, one of the functions of insulin is to conserve sodium and that is still one of the functions of insulin even in a ketogenic metabolism but if we drop our sodium too low, we can become insulin resistant and aldosterone will go up and we conserve sodium. That’s in very low sodium diets that are less than 500 milligrams of sodium per day.

A lot of people, if they are already insulin-resistant will not be very good at conserving sodium and they are going to have a big shift in insulin sensitivity hopefully when they remove carbohydrates, but there will be a transitional period at the beginning of a ketogenic diet where they will not be incredibly insulin-sensitive at the level of the kidney and the insulin level will drop rapidly.

I think these are the people in which the electrolyte thing becomes the biggest problem. So what we have is when they are on a glucose-based metabolism, the insulin is high because they are somewhat insulin-resistant, like 87% of the population appears to be in population studies with some degree of metabolic dysfunction.

So when they have a high level of insulin in the body due to insulin resistance, or a number of other factors, they are okay at conserving sodium and maybe they are using more sodium in processed foods. If they suddenly shift to a ketogenic diet, insulin levels will plummet ahead of their insulin sensitivity and there may not be enough insulin signaling in the kidney to properly conserve sodium. It’s this group of people where proper attention to electrolytes, predominantly sodium, must be done at the beginning of a ketogenic transition. I think within three to four weeks this adjusts. As the insulin sensitivity increases throughout the body, liver, muscle, kidney, everywhere, they are able to then absorb more of the sodium that they are eating. But one mistake that a lot of people make in the ketogenic transition, if they are coming from a metabolic dysfunction, is not eating enough sodium.

We’ve often been told sodium is bad for us, they are making one healthy decision and they think that eliminating sodium is a good healthy decision as well, but in this case it might be the wrong decision, at least temporarily. Long term, I have seen that people don’t tend to need quite as much sodium as they do in the ketogenic transition period and one of the things that we know looking at ICU literature, from critical care specialists, is that there are conditions in which there is a sodium wasting. There is a cerebral salt-wasting syndrome having to do with hemorrhage in the brain. In those patients, if we don’t replace sodium avidly, they will waste potassium and magnesium like crazy.

It’s all connected here. If people have insulin resistance and they transition to keto and they don’t get enough salt, then they will also waste magnesium and potassium along with it in a very aggressive way. That’s the main thing to think about, is those first three to four weeks, the electrolytes, specifically sodium with some amount of magnesium, potassium can be quite helpful as people are improving the insulin sensitivity at the level of the kidney.

Long term, for people, this appears to correct itself and if you look at animal meat, animal meat has a good amount of potassium in it. A pound of animal meat has about 1,500 milligrams of potassium, but only about 400 milligrams of sodium. I’ve had these interesting conversations with my friend, Tommy Wood, how much sodium would we have been getting ancestrally? I don’t think it was on the order of massive and massive amounts, I think it was much lower, but I think that we also would have been, again, very insulin sensitive, very adapted to this low-carb state and had more efficient signaling of insulin in the kidney to conserve sodium.

That’s sort of a long-winded way of saying that in the beginning of a ketogenic transition, electrolytes are very important. As people stay in that state, they can often lessen the amount that they need. But in people who have trouble, thinking about electrolytes is a good thing, probably because of salt-wasting at the level of the kidney due to inadequate insulin signaling as the levels go down.

DrMR: Very interesting. I didn’t realize the adaptation that can occur and that’s one question I get from patients, which is, will I need to be on electrolytes forever and I was inclined to say you would be, but I didn’t realize that there’s this potential to regain the insulin sensitivity therefore not need the electrolytes in the longer term. And would this same thing apply if you’re going … let’s say you’re not going full-blown keto or full-blown carnivore, but if you’re going lower carb, presumably you’re going to be much more insulin sensitive as you adapt. Would this same diminishing need for electrolytes occur in a lower-carb population?

DrPS: Yeah, I think so. I think any time there is a drop in insulin signaling, people are probably going to need electrolytes in the short term and then potentially going to have less need for it over time. There are definitely people, it’s anecdotal, but there are people in the carnivore community who don’t use any salt. I wouldn’t go that far, because I think that if we go below, in the studies that I’ve seen, if we go below 500 milligrams of sodium, not sodium chloride, but 500 milligrams of sodium per day, we certainly can trigger some insulin resistance. I think that for most people, my guess at this point is somewhere between 1500 milligrams and 2500 milligrams of sodium, not sodium chloride, is kind of an ancestrally consistent thing.

And then the question becomes as well, is there a sweet spot for sodium and if we’re over-salting our food, is that going to cause us to waste other electrolytes too? I think it’s a moving target, it will be interesting to see how it all evolves. But I conceptualize it is that it has to do with differential insulin signaling, sodium-wasting in the beginning with concomitant wasting of magnesium/potassium as we know human physiology does and if you just replace the sodium, usually you can hold onto magnesium/potassium, but a lot of people feel better with those supplemented as well.

The Gut Microbiome in a Carnivore Diet

DrMR: The final question I want to ask you here before I ask you about your website and book and all that good stuff is, what’s your take on what’s happening in the gut. I know that’s maybe a question to do another entire podcast on, but is there a short synopsis?

DrPS: Yeah, I think it’s really fascinating and I hopefully will get to on my podcast or we can do a part two and talk about this because this is a pretty big topic. Presuming, I mean there are a lot of places to go with this, we could talk about the mucus layer, we could talk about the microbiome, or we could talk about short-chain fatty acids, but let’s just talk about the microbiome to start.

I think, and I’d be curious about your perspective on this as well, I think that a bottom-up approach to looking at the microbiome is not serving us well. And what I mean by that is I do not think that as a medical community we understand what a healthy gut microbiome is at this point. I don’t think we have enough research data to say this is a healthy gut microbiome. You need more of this organism, less of this organism. I think we can sort of tell what an unhealthy microbiome looks like, if there’s low diversity or if there’s tons of proteo-bacteria, or tons of gram-negative anaerobic organisms hanging around if calmodulin is super high. I’m not a big fan, I know you’re not a big fan of zonulin, we don’t have a great measure of gastrointestinal permeability now, but there are a lot of measures that we can say, your gut is pissed off.

We can tell what a pissed off gut looks like. We really can’t do the reverse. We can’t really build a healthy gut from the ground up by looking at a gut either 16S or however we want to do the sequencing of the organisms in the gut and say you’re missing Roseburia or you’re missing fecal bacteria, you’re missing acamancia, therefore you don’t have a healthy gut microbiome. It doesn’t seem to work that way from what I’ve seen.

DrMR: Yeah. Agreed.

DrPS: I think that what we can say is that somebody is clinically doing well, no gas, no bloating, regular bowel movements that are easy to pass, wow, you probably have a great healthy gut. We don’t really even need to go looking at that. So often, criticisms of the carnivore diet say, “Well, we know that plant fiber benefits us and increases lactobacillus and bifido and those are, we know that those are healthy microbes’ ‘ and it’s like actually, we don’t. There’s plenty of evidence in Hadza hunter/gatherers, fascinating studies showing that they don’t really get anything out of bifidobacteria in their microbiome. Again, this is where people are getting too granular.

On the flip side, people will criticize a carnivore diet because there’s actually one study of a carnivore diet looking at the microbiome and they’ll say, “Look, when you give someone-” and granted, they didn’t give people a very well constructed carnivore diet, and even that study is diet rapidly and reproduces the human microbiome. It was a week-long study. But what they found in that study was that, this was actually an interesting one for short-chain fatty acids, they found that butyrate producers went down but that producers of other short-chain fatty acids, iso-butyrate, propionate, acetate, went up and to which I’ve often said on previous podcasts, yeah, I think our colonic epithelial cells can probably run on any short-chain fatty acid, they don’t necessarily need butyrate and people often look at this study and the authors of this study, who I think are connected with a plant-based ideal at Harvard said there’s an increase in bile-living organisms, therefore it’s bad.

This is, again, this ground-up construction of a microbiome saying you shouldn’t have Bilophila wadsworthia or that’s a bad thing. Actually we’re not sure that’s a bad thing, because there’s probably going to be more bile-living organisms on a carnivore diet, but some of the bile-acids are quite helpful. And some of the bile-acids have been associated with neuro-protection and so we just can’t …

I always bristle at these criticisms of microbiome in a carnivore kind of setting because we just don’t know enough and what I refer people to is, “Hey look, how is the patient doing clinically?” Because what we’ve seen clinically is that a lot of people have significant improvement in GI symptoms when they eliminate fiber, especially plant fiber. They get resolution of gas, bloating, constipation.

There are a number of published case reports now where people are having a resolution of inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, et cetera. And so, at a current level, I think gosh, if a carnivore diet or a zero-plant fiber diet were really so bad, wouldn’t we all just be getting Crohn’s. I should have Crohn’s by now because I haven’t had plant fiber in over a year. From a clinical perspective, I think it’s much more revealing at this point to say, “Look, we don’t see … ” and I’ve done multiple GI maps on myself throughout the time that I’ve been eating carnivore and calprotectins not elevated. I did one stool zonulin and it was low and I didn’t repeat it. It all looks pretty “normal”, as normal as a GI map could look.

You and I can talk about this offline as well, but when I look at a GI map, the main thing I look at is the last section, the last days, the inflammatory markers, and that’s really the main thing I want to see, if I don’t have any major microbes. If somebody doesn’t have C-Diff or blastocystis or H. pylori, okay great. How inflamed is their gut? And what I have not seen in my clients, what we have not seen in the community is people just having rampant inflammation as so many pundits would suggest might occur theoretically when you remove plant fiber.

I think that there is a lot more to learn here and we just don’t know how to construct the gut microbiome from the ground up.

DrMR: I think that’s actually really well said and I think for our audience, you’ve probably heard many of my perspectives on the gut and how we can’t, what I call in Healthy Gut, Healthy You, micromanage the ecosystem of the gut, fall very much in line with what Paul just said. I’m pretty much in agreement with everything you just said and just one or two thoughts to kind of echo your point. One of the biggest failures has been, let’s feed people’s gut bugs. Prebiotics and fiber supplements and high-fiber diets seem to work the worst the more symptomatic someone’s gut is, which has been evidenced by a plethora of research of different study setups in IBS and IBD and ironically, the less healthy or the more symptomatic someone’s gut is, the better they do on approaches that starve and don’t feed the gut.

This is where a low FODMAP diet works well, this is where an elemental diet works well. There are so many evidence points that just cause these gaping holes in the philosophy that we have to feed our gut bacteria with prebiotics and we need to bolster the production of short-chain fatty acids that I don’t know how anyone can be staunchly following that philosophy because there are, again, just so many contradictions to it.

We might even be able to posit, I’m not saying I fully agree with this, but it’s just an interesting contra-point to put out there, that you need to have a healthier gut to be able to do well on a higher-fiber diet and I think there’s probably more evidence showing that than there is showing you need to eat more fiber to have a healthier gut. I’m in agreement with those points. I just want to echo again that the diet that the host feels best on is probably going to be the best diet for the microbiota and we’ll eventually likely be smart enough to figure that out, but right now I think we’re so in the infancy of our understanding that we’re just making a lot of inferences that will probably be disproven and clarified as we learn more.

Dr. Ruscio’s Additional Resources

DrPS: Some of the studies of intermittent fasting and restructuring of the gut microbiome, I think are the most revealing. We can restructure our microbiome in a way that creates improved clinical outcomes at least in mouse models and in some human trials, by eating nothing. By eating nothing. And so how does that work? If we need plant fiber so much, how does that work that you can eat nothing and have that happen and when we do that … In this one trial that I was just looking at, restructuring the gut microbiome, by intermittent fasting prevents retinopathy and prolonged survival in a certain strain of mouse. They had an increase, they stayed consistent with known modulatory effects on metabolism. Measurement of bile acids demonstrated a significant increase in TUDCA, which is tauroursodeoxycholic, which is felt to be a neuro-protective bile acid, and that’s in intermittent fasting.

This is a very complex thing and for people to say you must eat lots of … I don’t think that shoving more and more plant fiber into people is the way we get them a healthy gut.

DrMR: Nope, I agree. And again, what I’ve seen in the clinic is usually the more unhealthy or symptomatic someone’s gut is, the more sensitive they have to be and our goal clinically is to get them healthy enough so that they can expand their diet. So it’s almost like the healthier you are, the more of these foods you can tolerate and the more sensitive your gut is, the more we have to revert in the direction of a carnivore to a greater lesser extent.

Now again, that’s not every case and there are exceptions to this rule that some patients when, and I think the LOFFLEX diet and the elemental diet are probably the two best examples of this, a higher carb diet tends to work well for them, but there is this commonality between even LOFFLEX and elemental, which is low fiber. And that’s definitely congruent with what we’re saying, which is feeding the gut bugs isn’t always the best strategy. To make it simple, folks, I’d say listen to your body first. It’s usually going to give you a good signal to follow.

DrPS: Have you seen the study, I’m sure you’ve seen the one on idiopathic constipation and complete removal of fiber in the World Journal of Gastroenterology?

DrMR: Oh yeah.

DrPS: Yeah, I’m sure you’ve quoted it before. That complete removal of fiber, it’s in a small study, I think each arm of the study was only 20 people, but in people with idiopathic constipation, complete removal of fiber resulted in 100%-

DrMR: It flies in the face of conventional thinking. But also, again, I hate to keep playing devil’s advocate here, I think the best data for fiber is probably for those who are constipated, but it’s not to say fiber is going to help everyone who is constipated. And this is why we see some people who go on a low fodmap diet and their constipation actually improves.

DrPS: Or Carnivore.

DrMR: So we should be open-minded in terms of let’s not cling too tightly to any one hypothesis and be okay with experimenting because if you can swallow the pill of we’re not as smart as we think we are, then you come down to the best way to get healthy is through experiment and listen to your body. A lot of this, I think becomes much more simpler when we just get some of the … well we think we know exactly what the microbiome should look like so we’re going to try to do X. I see so many patients who go to see another provider of whatever stripe and “well you’re low in short-chain fatty acids and you’re low in these bacteria so higher fiber, prebiotics”. They get flared, they feel terrible and they come to see me and it’s like, “Well, let’s put this “scientific” lab test aside for a minute and let’s just run through this simple, practical clinical algorithm, listen to your body, adjust along the way.” And what do you know, three months later the person is feeling great.

DrPS: Yeah. I love it. I think that it’s overly dogmatic to do those things, but you’re right. 95% of the time, if you’re low in lacto or bifido or butyrate, you’re going to say everything out there, whether it’s uBiome or Viome or any of the things people do to look at their gut, they are all going to say more fiber. That’s the clarion call now. Whatever promotional medicine practitioner you’re listening to, it’s more fiber. Yeah, I appreciate your position there. I would agree with you that it’s often not the answer, putting more plant fiber in there.

DrMR: Yep. Again, for people who want to get a really expanded narrative on this, see Healthy Gut, Healthy You because I really outline this in pretty copious detail in the sections on fiber. But that’s just a reference to point people to in case, let’s say your doctor is telling you, you’ve got to eat fiber and you’re feeling backed into a corner. If we’re going to be evidence-based on this question, the evidence does not point us in one direction here. We then get off of the fear train of I must eat fiber and then listen to your body.

Key Takeaways

Carnivore diet and the gut

- Often the gut appears to heal/improve from a carnivore diet

Episode Wrap-Up

Paul, I want to point people to resources for how to best execute a carnivore diet if they chose to do so. I know you have a book coming. You have a podcast, you have a website. Tell us more about all this.