What Is SIBO?

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) happens when there’s an abnormally high concentration of bacteria in the small intestine.

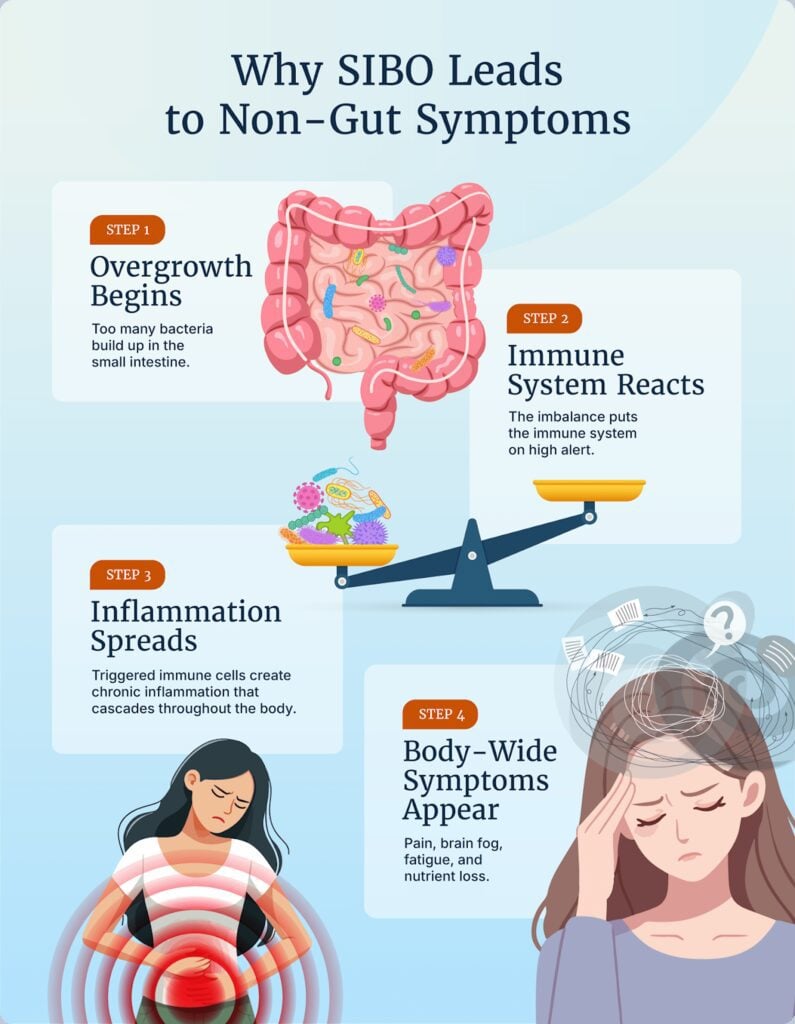

It’s normal for some bacteria to live in this part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, but excessive growth can disrupt the delicate balance, turning the usually beneficial relationship with gut microbes into a harmful one. Too much bacteria in the small intestine can interfere with nutrient absorption and produce toxins and gases that can lead to digestive symptoms.

When bacterial levels in the small intestine become too high, the immune system shifts into overdrive in an effort to restore balance. This heightened immune response can lead to inflammation, and if the inflammation persists, it can trigger chronic symptoms—signaling that it’s time to address SIBO.

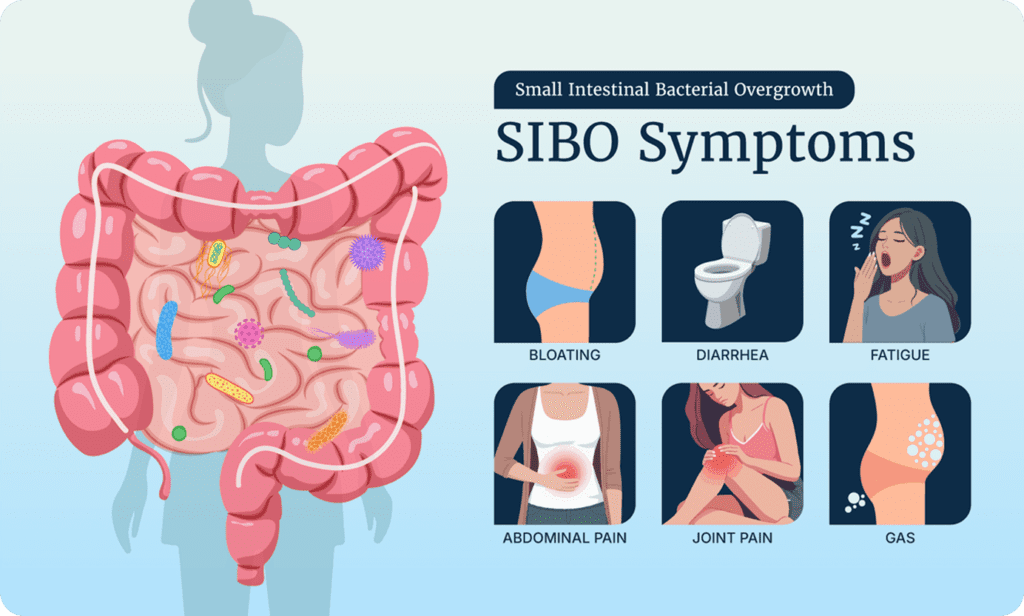

Symptoms of SIBO

SIBO symptoms can mimic many other gut conditions, which is why it can sometimes be tricky to diagnose. You’ll notice that SIBO symptoms can extend far beyond the gut—more on why that happens below. Common signs and symptoms of SIBO—based on well-supported research and our clinical observations include:

- Gut symptoms 1

- Excessive gas production

- Excessive gas production

- Abdominal pain, bloating

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Non-gut symptoms

- Non-gut symptoms

- Chronic fatigue 2

- Poor mood 3

- Brain fog 3

As I mentioned earlier, SIBO is linked to underlying health problems, like:

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Leaky gut 4

- Rosacea and psoriasis 5

- Restless legs syndrome 5

- Joint pain 5

- Headache

- Hypothyroidism 5 and increased TPO (thyroid peroxidase) antibodies 6

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) 5

- Diabetes 5

These types of overlapping conditions may help confirm whether SIBO is present.

NOTE: Because SIBO symptoms commonly overlap with IBS, SIBO is considered one possible driver of IBS 7.

How Long Does SIBO Last?

There isn’t one clear answer because the duration of SIBO depends on what caused it and how quickly it’s identified and treated. From our work in the clinic, we’ve seen that some people improve within weeks once they receive appropriate treatment, while others may experience recurring symptoms over months or even years if the underlying trigger isn’t addressed.

A few key factors influence how long SIBO lasts:

- Root cause: SIBO driven by temporary issues (like low stomach acid) may resolve more quickly than cases arising from chronic conditions (like chronic pancreatic insufficiency, immune deficiency disorders, or structural gut changes).

- Treatment response: Some people improve after one round of treatment, while others need several cycles or a combination of dietary, lifestyle, and medical approaches.

- Recurrence risk: Studies show that SIBO can come back within 9 months after treatment in about 30–40% of cases, especially if underlying motility issues (problems with how well food moves through your gut) or other risk factors are not addressed 8.

Bottom line: SIBO doesn’t usually go away on its own, but with the right treatment plan, many people notice significant improvements within a few weeks to a few months. Long-term resolution often depends on keeping root causes—like motility problems, reduced pancreatic enzymes, or low stomach acid—in check.

What Does SIBO Stool Look Like?

SIBO can change the appearance and consistency of your stool, mostly because bacterial overgrowth interferes with how you digest and absorb food—especially fats and carbohydrates. This can lead to noticeable differences in bowel movements, though symptoms will vary from person to person.

Some stool changes linked with SIBO may include:

- Oily or foul-smelling stools: SIBO can keep your gut from fully absorbing your macronutrients—fat, carbs, and protein. Fat malabsorption can cause greasy, hard-to-flush stools with a strong odor.

- Floating stools: Undigested fat or excess gas production may cause stools to rise in the toilet bowl.

- Soft, loose, or watery stools: Too much bacterial fermentation and malabsorption can make your stools less firm.

- Hard, lumpy stools: SIBO can also cause your poop to swing toward constipation instead of diarrhea.

- Presence of mucus: Extra mucus may appear as your gut lining reacts to irritation.

- Thin, pencil-like stools: Pencil poop can occur when gas and bloating affect motility.

These changes aren’t unique to SIBO—other gut conditions can cause similar patterns. But if you notice stool changes along with hallmark SIBO symptoms (like bloating, gas, and abdominal discomfort), it’s worth bringing up with your healthcare provider.

What Causes SIBO?

Research shows SIBO rarely has a single cause 9. Instead, it often results from overlapping issues that disrupt digestion:

- Poor motility: If your gut doesn’t move food along normally, bacteria have more opportunity to ferment it, leading to symptoms like gas and discomfort. Good motility is also needed to sweep out any unwanted bacteria that have taken up residence in the small intestine 9.

- Too little stomach acid, bile, or digestive enzymes: If digestive juices are too low, your body can’t fully break down food. This leaves more for bacteria to ferment, producing gas and symptoms 9.

- Structural changes: Structural changes in the digestive system—from surgery, fistulas, adhesions, or diverticulosis—can create pockets where food and bacteria accumulate and slow down motility. This can increase the likelihood of bacteria migrating from the large intestine to the small intestine 9.

- Underlying health conditions: Pancreatic insufficiency, immune deficiency disorders, and chronic pancreatitis can cause SIBO. Issues like IBS, hypothyroidism, diabetes, or scleroderma can make it more likely to develop 9.

- Poor diet: A diet low in nutrients and fiber but high in sugar, ultra-processed foods, and saturated fats might lead to imbalanced gut bacteria, slow down motility, and promote a leaky gut—all of which may make SIBO more likely to develop 10.

- Medications: A history of acid-lowering proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or medications (like opioids) that slow down motility can also tip the scales in favor of SIBO 9.

Foods to Avoid With SIBO

Because SIBO involves too much bacterial fermentation in the small intestine, certain foods can make symptoms worse. In particular, high-FODMAP foods (fermentable carbohydrates) often increase gas, bloating, and changes in bowel habits.

Some examples include:

- Beans and lentils

- Wheat and rye products

- Dairy foods high in lactose, like milk or ice cream

- Certain vegetables (onions, garlic, cauliflower, cabbage)

- Certain fruits (apples, pears, peaches, plums)

- Sweeteners like honey, agave, xylitol, or sorbitol

Even some prebiotic fiber supplements can trigger symptoms by feeding the overgrown bacteria.

That said, diet is just one part of managing SIBO, and it’s not a forever solution. In a later section, we’ll walk through how specific elimination diets—like Paleo or low FODMAP—can be used strategically with other treatments and then re-expanded once symptoms improve.

What Happens if SIBO Is Left Untreated?

SIBO doesn’t usually resolve on its own. Persistent bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine can disrupt nutrient absorption, gut motility, and overall digestive function, potentially leading to more chronic and serious health issues over time.

Some potential consequences of leaving SIBO untreated include:

- Chronic digestive symptoms: Ongoing bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation can become more frequent and harder to manage.

- Nutrient deficiencies: Overgrown bacteria compete with you for nutrients and may block your absorption. Untreated SIBO has been linked to deficiencies in iron, vitamin B12, and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) 11.

- Unintended weight changes: Some people lose weight due to malabsorption 9, while others might experience weight gain from inflammation and altered metabolism 12.

- Leaky gut and inflammation: Persistent bacterial overgrowth can irritate the intestinal lining, potentially contributing to increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut) and widespread inflammation 13.

- Secondary conditions: Long-standing SIBO may worsen or complicate conditions like IBS, celiac disease, chronic fatigue, or thyroid disorders. In more severe cases, it may lead to osteoporosis or anemia due to nutrient losses 9.

SIBO Testing: Do You Really Need It?

It’s natural to want a clear diagnosis, but here’s the truth: SIBO testing isn’t always the most useful first step. Tests can be expensive and unreliable, and—most importantly—they don’t always change what the best treatment looks like. Too often, people spend hundreds or thousands on tests that lead to the same standard diet and supplement plan they could have started right away.

Still, if you’re curious about testing—or if your doctor has suggested it—here are the most common types of SIBO tests:

The Main Types of SIBO Tests

- Direct Sampling (Small Intestinal Aspirate)

- Considered the “gold standard” because it measures bacteria directly

- Costly (often $1,500 or more without insurance), invasive, and typically only done during an endoscopy (medical procedure to look for problems in the GI tract)

- Breath Testing

- More common, easier, and less invasive

- You drink a sugar solution (glucose or lactulose), and labs analyze gases in your breath.

- Costs about $199–$350 without insurance

- Glucose testing has fewer false positives, whereas lactulose can give misleading results if measured beyond 80–90 minutes 14.

These tests can sometimes help, but false positives and false negatives are common, and the results don’t always match how you feel.

The good news is you don’t need test results to start getting better. Instead of spending hundreds on testing, we usually recommend starting with safe, evidence-based strategies that can bring relief right away. Adjusting your diet, using targeted probiotics, and making simple lifestyle changes can often reduce symptoms quickly—whether a test result says “SIBO” or not.

When SIBO Testing Might Make Sense

We typically recommend starting with safe, proven therapies first, but testing may be worthwhile if:

- You’ve already tried the diets, probiotics, and lifestyle changes in this list with little or no improvement.

- You’re scheduled for an upper endoscopy anyway (ask your doctor about adding a small-bowel aspirate).

- You and your healthcare provider want to distinguish between hydrogen-, methane-, or hydrogen-sulfide–dominant SIBO for targeted therapy.

- You have unusual or severe symptoms that need closer investigation.

For most people, though, relief may come faster from starting therapy than from waiting for lab results.

SIBO Treatment: Our Clinic’s Approach

At our clinic, we’ve found that SIBO responds best to a stepwise, layered approach rather than a single solution.

The core strategies we use for our clients include:

- Diet adjustments (like low FODMAP)

- Probiotics

- Herbal or pharmaceutical antimicrobials

- Elemental dieting (when needed)

- Lifestyle changes

Step 1: Diet

We always start with diet changes, but here’s the key: You don’t need to jump into the strictest elimination diet right away. In fact, many of our clients feel significantly better with a simple, less restrictive change.

Paleo Diet — The First, Gentle Step

A Paleo diet eliminates common gut irritants like gluten, dairy, soy, and processed foods while focusing on whole meat, fish, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and healthy fats. For many people, just making this shift is enough to calm symptoms.

CLINICAL TIP: We usually recommend giving Paleo a 2–3 week trial. If symptoms improve, stick with it. If not, move to the next step.

Low FODMAP Diet — Targeted Relief

If Paleo isn’t enough, the low FODMAP diet is one of the most researched approaches for SIBO and IBS, which often overlap 15 16.

FODMAP stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols—types of fermentable carbohydrates found in many foods. A low FODMAP diet limits fermentable carbs that feed gut bacteria, helping to reduce their numbers or push them back to the large intestine where they belong. By reducing FODMAPs, you essentially “starve out” some of the overgrown bacteria.

Most of the scientific research on a low FODMAP diet focuses on its use in helping people with IBS—and it can work very well for this purpose 17. However, recent research shows a low FODMAP diet may also be beneficial for SIBO 18.

We typically recommend trying the low FODMAP diet for 4–6 weeks. Once symptoms calm down, foods can often be reintroduced gradually.

PRACTICAL RESOURCE: The Monash University Low FODMAP app is an easy way to check the FODMAP content of almost any food.

Elemental Diet — The Most Restrictive, Short-Term Reset

For stubborn cases or when rapid relief is important, we may use an elemental diet for SIBO. This is a liquid formula of pre-digested nutrients that nourishes the body but deprives bacteria of fuel. The idea is to replace normal meals with elemental diet shakes to both starve bacteria and lighten the load on the gut, helping it heal.

Evidence is promising: In one study, 80% of patients had normal breath test results and 65% reported improved IBS symptoms after just two weeks on an elemental diet 19. A more recent study tested a two-week elemental diet in adults with SIBO or intestinal methanogen overgrowth. Results were positive: 73% had normal breath tests, 83% felt better overall, and no serious side effects occurred 20.

An elemental diet is a very restrictive dietary option, so it can feel intimidating—but the good news is, you don’t have to follow it full-time. Options include:

- Quick Reset (1–4 days): Gives the gut a rest, reduces bloating, and calms symptoms during flares

- Hybrid Approach: Replaces 1–2 meals a day with elemental shakes, while keeping the rest of the diet whole-food based, making it easier to sustain yet still effective

- Full Reset (1–3 weeks): Replaces all meals for up to 21 days—is highly effective but should be done only under the supervision of a healthcare provider

Step 2: Probiotics — Reset the Gut Microbiome

This step often surprises people—Why add more bacteria when too many bacteria are the problem? However, the science is clear—probiotics are one of the most effective tools available for managing SIBO.

In fact, one meta-analysis (a high-quality study of studies) showed that probiotics were nearly as effective as antibiotics at eliminating SIBO 21.

But it doesn’t have to be one or the other. Research also shows that probiotics can work in tandem with antibiotics, enhancing their effectiveness for getting rid of SIBO 22.

How Do Probiotics Reduce SIBO Symptoms?

Probiotics can help improve SIBO symptoms by:

- Competing against harmful bacteria for space and crowding them out 21

- Producing natural antimicrobials 23

- Improving gut motility 24

- Strengthening the gut barrier 25

- Balancing immune responses 26

Evidence snapshot:

- In one clinical trial, 10 billion CFU daily of probiotics cleared SIBO in 83% of people with liver disease—compared to 23% taking a placebo 27.

- A meta-analysis showed that people who took probiotics had a 61% higher SIBO clearance rate than those who didn’t 21.

- Combining probiotics with a low FODMAP diet cleared SIBO in 40% of patients within only two weeks—a great example of why we layer diet with natural supports 28.

Our Triple-Therapy Probiotic Approach for SIBO

You don’t need to stress about picking the perfect probiotic strain. However, research shows that multi-strain blends can work better than single strains, especially for conditions like IBS 29. After years of research and clinical practice, we formulated our Triple Therapy Approach, which combines these three major probiotic categories into one.

- Lactobacillus & Bifidobacterium blends → the most researched strains for balancing digestion and easing bloating

- Saccharomyces boulardii → a healthy yeast that naturally fights harmful microbes and calms inflammation

- Soil-based probiotics (Bacillus species) → resilient strains that help regulate the gut environment

Together, these may provide the broadest spectrum of benefits.

Probiotic timeline: Some people improve within weeks, but full benefits often take 2–3 months. Stopping too early is one reason probiotics sometimes seem ineffective.

Start Triple Therapy for SIBO Relief

CLINICAL TIP: We often have our sensitive clients start with just one category (usually Lactobacillus/Bifidobacterium) and layer in the others as tolerated.

Step 3: Lifestyle Strategies

Healing isn’t only about diet and supplements. Your other daily habits also influence your gut health, motility, and inflammation. At our clinic, we emphasize these five core lifestyle pillars that help turn short-term relief into lasting stability:

Sleep

Poor sleep can disrupt your circadian rhythm, weaken your immune defenses, and alter your gut microbiome balance. Research shows that inadequate sleep is linked to digestive symptoms 30 and slow healing 31. Prioritizing consistent bedtimes, getting 7-9 hours of quality sleep, limiting screens before bed, and creating a calming routine can all support gut recovery.

Stress Management

Stress can alter gut-brain communication and slow down motility, creating an environment where bacterial overgrowth may be more likely to return. Even short, daily stress-relief practices—like breathwork 32, meditation 33, or journaling 34—may improve things for people with IBS.

And mindfulness practices—paying attention to your thoughts, feelings, and body sensations without judging or trying to change them—can reduce inflammation in general 35.

Movement

Gentle to moderate activity can help “move things along” in the digestive tract. Studies show that walking, qigong (tai chi-like movements and breathing practices), other light aerobic activity, or strength training can reduce constipation and bloating 36. Unlike high-intensity exercise, which can stress the digestive system 37, restorative movement provides the optimal balance for gut health.

Nature & Sunlight

Exposure to natural light supports vitamin D production, which is critical for immune health and reducing inflammation 38. Time outdoors also strengthens circadian rhythms—helping you sleep better and improving digestion 39.

Social Connection

Strong relationships lower stress hormone levels and promote resilience. Isolation, on the other hand, is linked to higher inflammation and disease 40. And for people with IBS, negative or conflict-filled interactions may heighten stress and worsen symptoms 41.

Making time for supportive friends, family, or community activities is more than emotional nourishment—it’s medicine for your microbiome.

Bottom line: Together, these healthy lifestyle habits can set the foundation for long-term gut balance. Diet and supplements may calm symptoms, but it’s often these other daily rhythms that determine whether progress lasts.

Step 4: Natural Antimicrobials for SIBO

If diet changes, probiotics, and healthy lifestyle practices aren’t enough, the next layer of support we often use is antimicrobials.

What Are Antimicrobials?

Antimicrobials are natural or pharmaceutical substances that help reduce unwanted microbes in the gut. In the case of SIBO, the goal with antimicrobials is to gently reduce the excess bacterial population in the small intestine, allowing your gut to heal.

Unlike antibiotics that specifically kill bacteria—including good gut bacteria—many natural antimicrobials can attack a variety of unwanted microbes and have additional health benefits, such as reducing inflammation, supporting the immune system, or acting as antioxidants 42.

Best Options for SIBO:

- Rifaximin (antibiotic): About 71% effective for clearing SIBO but may be expensive without insurance 43

- Herbal antimicrobials: Can work at least as well as rifaximin 44 and also target yeast and parasites 45 46

Common Natural Antimicrobials We Use for SIBO Symptoms

In the clinic, we use a range of natural antimicrobials. Here are some of the most researched and commonly used herbal antimicrobials for SIBO:

- Oregano oil—naturally antibacterial and antifungal 46

- Berberine (from plants like goldenseal and barberry)—can support gut health 47, reduce inflammation 48, and improve blood sugar control 49

- Garlic extract (allicin)—has antibacterial and antifungal properties, though it’s often better tolerated in supplement form than as raw garlic 46

- Artemisia (wormwood)—traditionally used against parasites, also has antibacterial effects 50

- Pau d’Arco—shows activity against bacterial and fungal overgrowths 51

Evidence for Herbal Antimicrobials:

- Again, one study found that herbal therapy was at least as effective as rifaximin in people with SIBO 44.

- A randomized controlled trial (gold standard type of study) found that using herbal antimicrobials together with a low-FODMAP diet and probiotics improved symptoms more effectively than standard antibiotics plus a low-FODMAP diet—and also helped clear SIBO 52.

A key caution: Herbal antimicrobials should always be used under the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider. Even though they are natural, they’re powerful and can cause harm if misused—especially in people with weakened immune systems 53.

How We Use Antimicrobials for SIBO in Practice

After years of testing different herbs in the clinic and reviewing the research, we saw what worked—and what left our clients frustrated. The challenge was never whether herbal antimicrobials were effective (they are), but how to combine and rotate them without overwhelming people.

We designed the Biota-Clear System to solve that problem. Our simple, research-backed formulas cover bacteria, yeast, and parasites—so you get the benefits without the guesswork.

Month 1

- Biota-Clear 1a → Oregano oil

- Biota-Clear 1b → Tribulus terrestris, caprylic acid, black walnut, barberry, phellodendron, wormwood, black walnut

Month 2

- Biota-Clear 2a → Wormwood, olive leaf, berberine, artemisinin

- Biota-Clear 2b → Biotin, pau d’arco, black walnut, caprylic acid, oregano

This progression helps ensure that we’re not just knocking down bacteria but also addressing other microbes that may be contributing to symptoms. By rotating the formulas, we also reduce the risk of microbes adapting to the herbs or clients plateauing in their progress.

NOTE: Some people experience mild “die-off” symptoms or a Herxheimer reaction (temporary worsening as bacteria are cleared). These usually resolve within a few days. If symptoms persist for longer than a week, it’s best to pause and focus on a balanced diet, lifestyle, and probiotics.

Final Thoughts: A Healing Strategy for SIBO Tailored to You

Healing SIBO doesn’t have to feel overwhelming. The truth is, you don’t need the strictest diet, expensive tests, or complicated protocols to start getting better. By taking a step-by-step approach—first focusing on a gut-friendly diet, then adding probiotics and healthy lifestyle habits, and using stronger treatments like antimicrobials or an elemental diet only if needed—you can ease symptoms, restore gut balance, and reclaim your health.

We’ve seen this approach work time and again in our clinic. And although no two journeys look exactly alike, the right plan for you is often simpler than you think.

If you’ve already tried adjusting your diet, taking probiotics, and using antimicrobials but still aren’t getting better, it may mean there’s a deeper issue—and that’s when it’s important to get help from a professional.

If you’re feeling stuck, or if you’d like guidance tailoring this plan to your unique situation, our clinic team is here to help. We’ll walk with you step by step, adjust as needed, and make sure you’re not wasting time, money, or energy on treatments you don’t need.

Because you don’t just deserve relief—you deserve lasting health and confidence in your gut.

The Ruscio Institute has developed a range of high-quality formulations to help our clients and audience. If you’re interested in learning more about these products, please click here. Note that there are many other options available, and we encourage you to research which products may be right for you. The information on DrRuscio.com is for educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

- Takakura W, Pimentel M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome – An Update. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 10;11:664. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00664. PMID: 32754068. PMCID: PMC7366247.

- Grace E, Shaw C, Whelan K, Andreyev HJN. Review article: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth–prevalence, clinical features, current and developing diagnostic tests, and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Oct;38(7):674–88. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12456. PMID: 23957651.

- Kossewska J, Bierlit K, Trajkovski V. Personality, Anxiety, and Stress in Patients with Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth Syndrome. The Polish Preliminary Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Dec 21;20(1). DOI: 10.3390/ijerph20010093. PMID: 36612414. PMCID: PMC9819554.

- Riordan SM, McIver CJ, Thomas DH, Duncombe VM, Bolin TD, Thomas MC. Luminal bacteria and small-intestinal permeability. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997 Jun;32(6):556–63. DOI: 10.3109/00365529709025099. PMID: 9200287.

- Efremova I, Maslennikov R, Poluektova E, Vasilieva E, Zharikov Y, Suslov A, et al. Epidemiology of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. World J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun 14;29(22):3400–21. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i22.3400. PMID: 37389240. PMCID: PMC10303511.

- Konrad P, Chojnacki J, Kaczka A, Pawłowicz M, Rudnicki C, Chojnacki C. [Thyroid dysfunction in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2018 Jan 23;44(259):15–8. PMID: 29374417.

- Ghoshal UC, Nehra A, Mathur A, Rai S. A meta-analysis on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with different subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun;35(6):922–31. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.14938. PMID: 31750966.

- Rao SSC, Bhagatwala J. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: clinical features and therapeutic management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019 Oct;10(10):e00078. DOI: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000078. PMID: 31584459. PMCID: PMC6884350.

- Sorathia SJ, Rivas JM. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. PMID: 31536241.

- Severino A, Tohumcu E, Tamai L, Dargenio P, Porcari S, Rondinella D, et al. The microbiome-driven impact of western diet in the development of noncommunicable chronic disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2024 Sep;72:101923. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpg.2024.101923. PMID: 39645277.

- Wielgosz-Grochowska JP, Domanski N, Drywień ME. Identification of SIBO Subtypes along with Nutritional Status and Diet as Key Elements of SIBO Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jul 4;25(13). DOI: 10.3390/ijms25137341. PMID: 39000446. PMCID: PMC11242202.

- Yao Q, Yu Z, Meng Q, Chen J, Liu Y, Song W, et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in obesity and its related diseases. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023 Jun;212:115546. DOI: 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115546. PMID: 37044299.

- Kinashi Y, Hase K. Partners in leaky gut syndrome: intestinal dysbiosis and autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2021 Apr 22;12:673708. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.673708. PMID: 33968085. PMCID: PMC8100306.

- Losurdo G, Leandro G, Ierardi E, Perri F, Barone M, Principi M, et al. Breath Tests for the Non-invasive Diagnosis of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 Jan 30;26(1):16–28. DOI: 10.5056/jnm19113. PMID: 31743632. PMCID: PMC6955189.

- Achufusi TGO, Sharma A, Zamora EA, Manocha D. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: comprehensive review of diagnosis, prevention, and treatment methods. Cureus. 2020 Jun 27;12(6):e8860. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.8860. PMID: 32754400. PMCID: PMC7386065.

- Black CJ, Staudacher HM, Ford AC. Efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2022 Jun;71(6):1117–26. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325214. PMID: 34376515.

- Altobelli E, Del Negro V, Angeletti PM, Latella G. Low-FODMAP Diet Improves Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017 Aug 26;9(9). DOI: 10.3390/nu9090940. PMID: 28846594. PMCID: PMC5622700.

- Więcek M, Panufnik P, Kaniewska M, Lewandowski K, Rydzewska G. Low-FODMAP Diet for the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Remission of IBD. Nutrients. 2022 Oct 29;14(21). DOI: 10.3390/nu14214562. PMID: 36364824. PMCID: PMC9658010.

- Pimentel M, Constantino T, Kong Y, Bajwa M, Rezaei A, Park S. A 14-day elemental diet is highly effective in normalizing the lactulose breath test. Dig Dis Sci. 2004 Jan;49(1):73–7. DOI: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000011605.43979.e1. PMID: 14992438.

- Rezaie A, Chang BW, de Freitas Germano J, Leite G, Mathur R, Houser K, et al. Effect, Tolerability, and Safety of Exclusive Palatable Elemental Diet in Patients with Intestinal Microbial Overgrowth. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Apr 4; DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2025.03.002. PMID: 40189034.

- Zhong C, Qu C, Wang B, Liang S, Zeng B. Probiotics for Preventing and Treating Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Current Evidence. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017 Apr;51(4):300–11. DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000814. PMID: 28267052.

- Martyniak A, Wójcicka M, Rogatko I, Piskorz T, Tomasik PJ. A comprehensive review of the usefulness of prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics in the diagnosis and treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Microorganisms. 2025 Jan 1;13(1). DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms13010057. PMID: 39858825. PMCID: PMC11768010.

- Fijan S. Probiotics and their antimicrobial effect. Microorganisms. 2023 Feb 19;11(2). DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms11020528. PMID: 36838493. PMCID: PMC9963354.

- Lai H, Li Y, He Y, Chen F, Mi B, Li J, et al. Effects of dietary fibers or probiotics on functional constipation symptoms and roles of gut microbiota: a double-blinded randomized placebo trial. Gut Microbes. 2023;15(1):2197837. DOI: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2197837. PMID: 37078654. PMCID: PMC10120550.

- Ghorbani Z, Shoaibinobarian N, Noormohammadi M, Taylor K, Kazemi A, Bonyad A, et al. Reinforcing gut integrity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials assessing probiotics, synbiotics, and prebiotics on intestinal permeability markers. Pharmacol Res. 2025 Jun;216:107780. DOI: 10.1016/j.phrs.2025.107780. PMID: 40378939.

- Liao W, Chen C, Wen T, Zhao Q. Probiotics for the Prevention of Antibiotic-associated Diarrhea in Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jul 1;55(6):469–80. DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001464. PMID: 33234881. PMCID: PMC8183490.

- Maslennikov R, Efremova I, Ivashkin V, Poluektova E, Zharkova M. Probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii in the Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Decompensated Cirrhosis. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022 Jun;6:749. DOI: 10.1093/cdn/nzac062.018. PMCID: PMC9194055.

- Bustos Fernández LM, Man F, Lasa JS. Impact of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 on Bacterial Overgrowth and Composition of Intestinal Microbiota in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients: Results of a Randomized Pilot Study. Dig Dis. 2023 Jan 11;41(5):798–809. DOI: 10.1159/000528954. PMID: 36630947.

- Xie P, Luo M, Deng X, Fan J, Xiong L. Outcome-Specific Efficacy of Different Probiotic Strains and Mixtures in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2023 Sep 4;15(17). DOI: 10.3390/nu15173856. PMID: 37686889. PMCID: PMC10490209.

- Wang N, Liu X, Ye W, Shi Z, Bai T. Impact of shift work on irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Jun 24;101(25):e29211. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029211. PMID: 35758349. PMCID: PMC9276432.

- Sleep Deprivation and Deficiency – How Sleep Affects Your Health | NHLBI, NIH [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep-deprivation/health-effects

- Katherine Jurek M, Seavey H, Guidry M, Slomka E, Hunter SD. The effects of slow deep breathing on microvascular and autonomic function and symptoms in adults with irritable bowel syndrome: A pilot study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022 May;34(5):e14275. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.14275. PMID: 34595801.

- Shah K, Ramos-Garcia M, Bhavsar J, Lehrer P. Mind-body treatments of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: An updated meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2020 May;128:103462. DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103462. PMID: 32229334.

- Laird KT, Stanton AL. Written expressive disclosure in adults with irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021 May;43:101374. DOI: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101374. PMID: 33826992. PMCID: PMC8172117.

- Dunn TJ, Dimolareva M. The effect of mindfulness-based interventions on immunity-related biomarkers: a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022 Mar;92:102124. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102124. PMID: 35078038.

- Gao R, Tao Y, Zhou C, Li J, Wang X, Chen L, et al. Exercise therapy in patients with constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019 Feb;54(2):169–77. DOI: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1568544. PMID: 30843436.

- Edwards KH, Ahuja KD, Watson G, Dowling C, Musgrave H, Reyes J, et al. The influence of exercise intensity and exercise mode on gastrointestinal damage. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021 Sep;46(9):1105–10. DOI: 10.1139/apnm-2020-0883. PMID: 33725465.

- Martens P-J, Gysemans C, Verstuyf A, Mathieu AC. Vitamin d’s effect on immune function. Nutrients. 2020 Apr 28;12(5). DOI: 10.3390/nu12051248. PMID: 32353972. PMCID: PMC7281985.

- Billey A, Saleem A, Zeeshan B, Dissanayake G, Zergaw MF, Elgendy M, et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbance and functional dyspepsia: A systematic review to understand mechanisms and implications on management. Cureus. 2024 Aug 3;16(8):e66098. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.66098. PMID: 39229406. PMCID: PMC11370990.

- Albasheer O, Abdelwahab SI, Zaino MR, Altraifi AAA, Hakami N, El-Amin EI, et al. The impact of social isolation and loneliness on cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and bibliometric investigation. Sci Rep. 2024 Jun 4;14(1):12871. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-63528-4. PMID: 38834606. PMCID: PMC11150510.

- Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Firth R, Keefer L, Brenner DM, Guy K, et al. Negative aspects of close relationships are more strongly associated than supportive personal relationships with illness burden of irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2013 Jun;74(6):493–500. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.03.009. PMID: 23731746. PMCID: PMC3673032.

- Healthy Gut Healthy You [Internet]. [cited 2022 Feb 2]. Available from: https://drruscio.com/gutbook/

- Gatta L, Scarpignato C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: rifaximin is effective and safe for the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Mar;45(5):604–16. DOI: 10.1111/apt.13928. PMID: 28078798. PMCID: PMC5299503.

- Chedid V, Dhalla S, Clarke JO, Roland BC, Dunbar KB, Koh J, et al. Herbal therapy is equivalent to rifaximin for the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014 May;3(3):16–24. DOI: 10.7453/gahmj.2014.019. PMID: 24891990. PMCID: PMC4030608.

- Shor SM, Schweig SK. The Use of Natural Bioactive Nutraceuticals in the Management of Tick-Borne Illnesses. Microorganisms. 2023 Jul 5;11(7). DOI: 10.3390/microorganisms11071759. PMID: 37512931. PMCID: PMC10384908.

- Karpiński TM, Ożarowski M, Seremak-Mrozikiewicz A, Wolski H. Anti-Candida and Antibiofilm Activity of Selected Lamiaceae Essential Oils. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2023 Feb 16;28(2):28. DOI: 10.31083/j.fbl2802028. PMID: 36866556.

- Chen C, Tao C, Liu Z, Lu M, Pan Q, Zheng L, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Berberine Hydrochloride in Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Phytother Res. 2015 Nov;29(11):1822–7. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.5475. PMID: 26400188.

- Vahedi-Mazdabadi Y, Shahinfar H, Toushih M, Shidfar F. Effects of berberine and barberry on selected inflammatory biomarkers in adults: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Phytother Res. 2023 Dec;37(12):5541–57. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.7998. PMID: 37675930.

- Zhao JV, Huang X, Zhang J, Chan Y-H, Tse H-F, Blais JE. Overall and Sex-Specific Effect of Berberine on Glycemic and Insulin-Related Traits: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Nutr. 2023 Oct;153(10):2939–50. DOI: 10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.08.016. PMID: 37598753.

- Batiha GE-S, Olatunde A, El-Mleeh A, Hetta HF, Al-Rejaie S, Alghamdi S, et al. Bioactive Compounds, Pharmacological Actions, and Pharmacokinetics of Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Jun 23;9(6). DOI: 10.3390/antibiotics9060353. PMID: 32585887. PMCID: PMC7345338.

- Zhang J, Hunto ST, Yang Y, Lee J, Cho JY. Tabebuia impetiginosa: A Comprehensive Review on Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Immunopharmacological Properties. Molecules. 2020 Sep 18;25(18). DOI: 10.3390/molecules25184294. PMID: 32962180. PMCID: PMC7571111.

- Redondo-Cuevas L, Belloch L, Martín-Carbonell V, Nicolás A, Alexandra I, Sanchis L, et al. Do herbal supplements and probiotics complement antibiotics and diet in the management of SIBO? A randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. 2024 Apr 7;16(7). DOI: 10.3390/nu16071083. PMID: 38613116. PMCID: PMC11013329.

- Purssell E. Antimicrobials. In: Hood P, Khan E, editors. Understanding pharmacology in nursing practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 147–65. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-32004-1_6.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!