Atrophic Gastritis: Everything You Need to Know

Symptoms, Risk Factors, Diagnosis and Treatments

- What Is Atrophic Gastritis?|

- Symptoms|

- Causes|

- Helicobacter Pylori Infection|

- Diagnosis|

- Treatment Options|

- Recommended Products|

Atrophic gastritis, or chronic stomach irritation, is an often unrecognized cause of chronic symptoms.

Some research has shown that atrophic gastritis patients tend to be asymptomatic, but less obvious symptoms like fatigue, generalized abdominal pain, and bloating might actually be signs of the condition.

Atrophic gastritis is often not diagnosed unless symptoms become more severe. But identifying and treating atrophic gastritis earlier can help you to get to the root cause of your symptoms, prevent complications like low stomach acid and nutrient malabsorption, and feel better.

This article will give you an overview of what atrophic gastritis is, what causes it, and how to treat it.

Understanding Gastritis: A Snapshot

Common Symptoms:

- Upper abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Quickly feeling full when eating

- Fatigue

- Pale complexion

Possible Causes:

Treatments:

- Identifying food sensitivities

- Eradicating H. pylori, with probiotics, antibiotics, and/or antimicrobials

- Reducing inflammation

- Improving absorption and low levels of B12, iron, and vitamin D

- Reducing cancer risk

What Is Atrophic Gastritis?

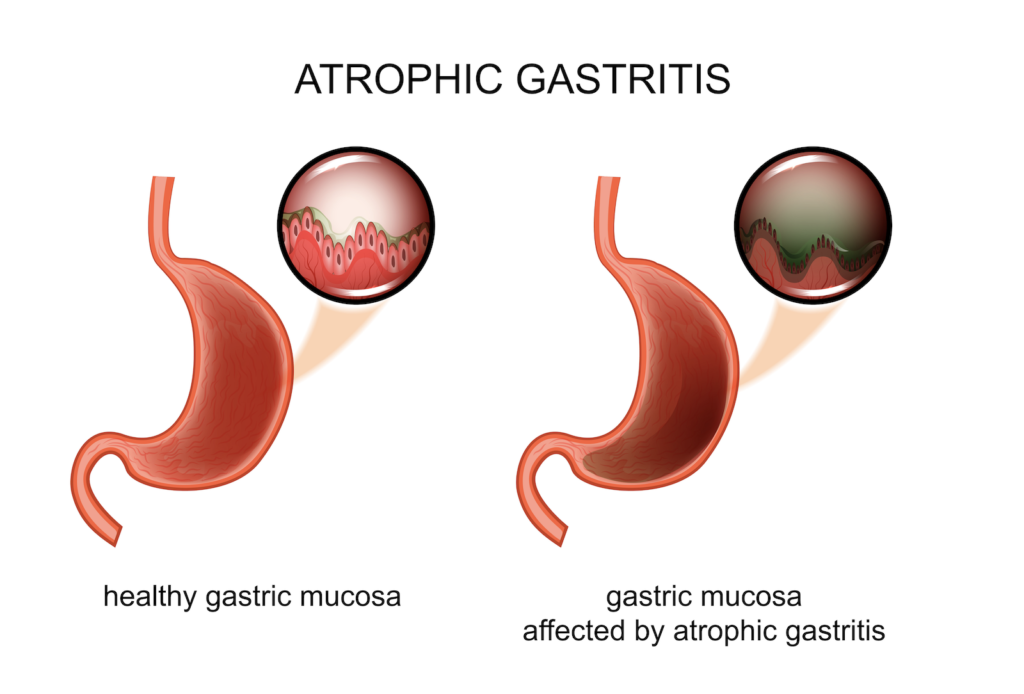

Gastritis is irritation of the stomach. Atrophic gastritis means that the irritation has become severe and has been happening for a long time.

In gastritis, the lining of the stomach (gastric mucosal lining) has become inflamed. There can be multiple reasons for this inflammation, and diagnosis will help discover the contributing factors and rule out any other gastric conditions.

Atrophic gastritis can either be autoimmune in nature or brought on by environmental factors (especially H. pylori infection).

Importantly, the main resulting issue from atrophic gastritis is low stomach acid (hypochlorhydria). This can cause a host of other issues, including malabsorption, which we will discuss in depth later.

Prevalence of Atrophic Gastritis

Around 23.9%-31.6% of the population has chronic atrophic gastritis. It’s most prevalent in people aged 35-44 [4]. Those at increased risk may be those with iron deficiency anemia, chronic indigestion, or continuous use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs are often used for treatment of reflux) [4].

Common Symptoms of Atrophic Gastritis

Interestingly, most people are not thought to experience symptoms from atrophic gastritis [1], although one study found that 30.1% of people who had pain, bloating, or other symptoms in the upper gastrointestinal tract had atrophic gastritis [4].

Those who do experience digestive symptoms may experience:

- Nondescript upper abdominal pain

- Burning or bloated feeling in the stomach

- Nausea

- Feeling abnormally full after eating small amounts of food [5]

There are also non-digestive symptoms that may surprise you:

- Fatigue

- Pale complexion (combined with fatigue, this may be a sign of anemia or iron deficiency, which may only show up in testing)

- Neurological symptoms such as sensory ataxia (decreased or loss of sensation in legs and feet), and impaired sense of vibration, are found in 6.1% of people [6]

Atrophic Gastritis, Low Stomach Acid, and Nutrient Deficiencies

Gastritis often comes with additional health complications, especially low stomach acid and nutrient deficiencies.

In cases of atrophic gastritis, chronic inflammation can damage the mucosal lining, leading to the breakdown of gastric epithelial (stomach lining) cells. In particular, it may degrade parietal cells (epithelial cells in the stomach) which create hydrochloric acid (stomach acid), leading to lower acid secretion [1].

Chronic low gastric acid may lead to the following:

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Iron deficiency [7, 8]

- Folate deficiency

- Loss of oxyntic mucosa (which assists in digesting food)

- Loss of intrinsic factor (which helps absorb B12)

- Pernicious anemia (inadequate red blood cells as a result of the intestines being unable to absorb B12) [9]

- Peptic ulcers

This damage done to the gastric mucosa (stomach lining) and the resulting loss of digestive enzymes and malabsorption often lead to some of the less obvious symptoms of atrophic gastritis such as fatigue, brain fog, and pale skin.

What Causes Atrophic Gastritis?

The possible causes of atrophic gastritis all relate to chronic inflammation and may be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors [9]. Some of the factors that may contribute to the pathogenesis of gastritis include:

- H. pylori infection [1]

- Autoimmunity [2, 3]

- Inflammation caused by a variety of factors

- Use of PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) were shown in observational studies to possibly increase the incidence of gastric atrophy, while a statistical analysis of randomized clinical trials (the highest grade of research studies) has shown no clear evidence that PPIs increase risk of atrophic gastritis [10, 11].

Autoimmune Atrophic Gastritis

While some cases of gastritis are caused by infection or other factors, some cases are caused by autoimmunity. This is generally referred to as autoimmune atrophic gastritis, but other terms including autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis may also be used to further subcategorize autoimmune gastritis.

In autoimmune gastritis, there is an inappropriate immune response where the immune system attacks the interior lining of the stomach, causing inflammation [9, 12].

Normally, the body creates temporary inflammation as part of a response to threats from foreign particles, bacteria, or viruses that may cause the body harm. An inappropriate immune response happens when the immune system attacks something that is probably not harmful, or it sends too much of an immune response to a possible pathogen. This creates unnecessary or excessive inflammation that can become chronic.

Helicobacter Pylori Infection (H. Pylori)

Cases of gastritis that are not autoimmune may instead be caused by an H. pylori infection [1, 12].

H. pylori is a type of spiral-tailed pathogenic bacteria that mainly lives in the stomach [13]. The H. pylori bacteria burrow into the stomach lining which inflames the stomach lining. This inflammation breaks down the cells that create hydrochloric acid, causing chronic low acid in the stomach [14]. It can also lead to mucosal atrophy (loss of appropriate glands in the lining of the stomach), commonly seen in atrophic gastritis.

Associated Risks with Atrophic Gastritis

Atrophic gastritis can lead to other issues that are important to know about. Although rare, chronic atrophic gastritis is associated with a higher incidence of two types of cancer [1]:

- Gastric adenocarcinoma (gastric cancer), which is the fifth most common cancer in the world, accounting for 1.5% of new cancer diagnoses each year in the US, and is linked to H. pylori infection.

- Neuroendocrine type-1 gastric carcinoid tumor, which is secondary not only to atrophic gastritis (because of elevated serum gastrin levels or hypergastrinemia) but also pernicious anemia. This cancer is associated with hyperplasia of the enterochromaffin-like cells (an increase of the enterochromaffin cells, which are cells in the oxyntic mucosa that contain histamine) [15].

It is important to note that gastric cancer is on the decline, in part due to fewer H. pylori infections, which is why eradicating H. pylori is an important factor in gastritis treatment [16].

Other autoimmune diseases have been found in up to 54.5% of people with atrophic gastritis [6, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24], including:

- Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Grave’s disease (immune system attacks the thyroid)

- Type I diabetes

- Vitiligo (skin color is missing in patches)

- Celiac disease

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Connective tissue disease

- Psoriasis

Diagnosing Atrophic Gastritis

Because atrophic gastritis often does not come with symptoms, diagnosis often comes after many years, once symptoms are more severe [3].

Diagnosis should include discovering if the atrophic gastritis is due to autoimmunity or H. pylori infection.

Biopsy

Biopsies of the antrum (lower chamber) of the stomach, done with an endoscopy, may be done to determine correct location of the atrophic gastritis, check for precancerous lesions, and to see if there is any intestinal metaplasia. Intestinal metaplasia is when the cells that create the lining of your stomach (gastric body) are changed or replaced [4].

A biopsy is the most reliable way of finding metaplastic atrophic gastritis. However, by the time this shows up on a biopsy, the disease is very far advanced. This is when we start to see issues with anemia and other malabsorption concerns [9].

Is Antibody Testing Helpful for Atrophic Gastritis?

The immune system produces antibodies when it detects harmful substances. Autoantibodies are directed against your own body’s cells or tissues. These non-endoscopic tests can help detect levels of inflammation and levels can change over time with the severity of the disease [9].

However, a few observational studies have found that antibody levels seem to rise for a time, peak, and then fall again, even if gastritis may still be present [25]. In one study, the antibody levels did not change at all, even in people who had progression of the disease [26].

The following antibody tests are helpful but are only part of the diagnostic process:

- Immunofluorescence testing or ELISA (enzyme linked immunosorbent assay) testing to identify parietal cell autoantibodies [3]

- Anti-intrinsic factor antibodies

- Anti-H. pylori antibodies [12]

- Gastrin-17 may also be added to the list of antibody tests to look for oxyntic gland atrophy, which leads to higher gastrin production in the antrum of the stomach [12].

Pepsinogen Tests

Pepsinogen is secreted by the gastric wall (stomach), and the stomach converts the pepsinogen to pepsin, a digestive enzyme. Low levels of pepsinogen may indicate gastritis [3].

Treatment Options for Atrophic Gastritis

Treatment will depend on what type of atrophic gastritis you have and what additional issues you’ve experienced as a result of gastritis.

Most treatments for gastritis, regardless of type, include:

- Reducing inflammation

- Identifying and removing food triggers

- Addressing malabsorption and nutritional deficiencies

- Reducing cancer risk

- Eradicating helicobacter pylori infection if present

In autoimmune gastritis, there is no standard treatment. However, some of the supplements and probiotics below may be helpful. A key to autoimmune gastritis treatment would be to find the underlying root cause of the immune dysfunction.

For atrophic gastritis caused by H. pylori, it’s important to eradicate the H. pylori infection [1, 27]. H. pylori treatment traditionally includes antibiotics [28] and sometimes PPI’s (proton-pump inhibitors) [29] and antimicrobials [30].

More natural H. pylori treatment may include probiotics — in particular, a range of Lactobacillus strains [31] as well as herbal antimicrobials [32]. We’ll cover the use of probiotics for H. pylori in greater detail below.

Dietary Changes

Diet has not been found to be a direct cause of atrophic gastritis. However, certain foods may aggravate an inflamed gastric lining. So, some people may have increased abdominal pain or other symptoms with foods such as spicy foods, wheat, and alcohol [33].

In one observational study, people self-identified certain dietary habits such as eating a lot of sugar, eating too fast, and eating leftovers as contributing to their symptoms [34]. This is why it can be helpful to record what you eat and any symptoms you may have. It can help in diagnosis and figuring out the root cause of your illness.

An elimination diet based on the Paleo diet is often a good starting point to discover which, if any, foods contribute to your gastritis. The Paleo diet eliminates many common food triggers and allergens, including gluten, and dairy.

Here’s how to get started with an elimination diet:

- Consider whether there are any foods that you already know aggravate your symptoms, and eliminate these right away.

- Begin a 3-4 week elimination period in which you avoid common trigger foods. I recommend starting with a Paleo diet framework in most cases.

- If this helps to resolve symptoms, begin a reintroduction period in which you add one eliminated item back into your diet at a time (every 2-3 days), monitoring your symptoms. This should help you to identify which foods you should continue to avoid and which ones you can tolerate. Do not reintroduce processed or sugary foods, which are not healthy for anyone.

- If the elimination period doesn’t help to resolve symptoms, consider a trial of a more specialized diet, such as a low FODMAP diet.

Addressing Malabsorption

Depending on the cause of atrophic gastritis and any other issues you may be having, some supplements may help address malabsorption.

B12 and Iron

Two studies have shown that B12 injections can help reduce general stomach autoimmunity [35]. Another five-year, clinical trial found that oral B12 without intrinsic factor was effective at resolving malabsorption and maintaining healthy B12 levels and treating pernicious anaemia, which may be found in atrophic gastritis [36].

Supplementation with B12 and iron may help resolve vitamin B12 deficiency and prevent anemia and neurological issues that often come with atrophic gastritis [3].

High oral doses of 500-1,000 micrograms/day of intramuscular cobalamin (B12) have been found to help with gastric atrophy. Often, treatment starts more frequently, such as every other day, then becomes weekly and then monthly for life [9].

Vitamin D

Vitamin D supplementation may be used to help prevent secondary health concerns that may come from having atrophic gastritis:

- While rare, hyperparathyroidism from vitamin D deficiency has been found in 12.1% of people with chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis (CAAG.) The rate of hyperparathyroidism in the general population is 7% [37].

- Vitamin D helps support the immune system, which can be beneficial in autoimmune gastritis [38].

Probiotics and H. pylori Treatment

Probiotics have been shown to be helpful in eradicating H. pylori infection. A 2019 meta analysis found that people given probiotics as part of their H. pylori treatment had higher rates of eradication than compared with controls [39].

Probiotics help eradicate H. pylori by competing for surface receptors in the stomach and not allowing the H. pylori to attach to the stomach lining. The probiotics that were found to be the most effective were a broad range of Lactobacillus.

Studies on probiotic supplementation for eradicating H. pylori infection show probiotics can:

- Eradicate H. pylori in 14-16% of cases [40]

- Improve treatment success by 10-15% compared to therapy without probiotics [41, 42]

- Suppress H. pylori in the stomach and improve stomach microbiota [43]

- When used in conjunction with antibiotics, increase eradication of H. pylori and reduce the side effects from antibiotics [44]

Not all studies agree. One meta-analysis found that probiotics plus standard antibiotic therapy did not improve eradication rates better than placebo plus standard antibiotic therapy [45].

However, a wide range of systematic reviews and meta-analysis show that probiotics are beneficial in the treatment of H. pylori. Additionally, long-term use of probiotics also appears to reduce the risk of developing disorders associated with the gastric inflammation caused by H. pylori infection, such as ulcers, gastritis, and cancer [46]. Given this data, probiotics should be considered as important in the treatment of H. pylori infection.

Additional Supplements for Gut Healing

There are a few amino acid supplements that have been found to assist in eradication of H. pylori and healing the gut lining:

- N-acetylcysteine (NAC): N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been shown to help eradicate H. pylori, and may prevent H. pylori-induced gastritis and to improve gut healing for those who have the condition [47, 48, 49].

- Glutathione has been found to help eradicate H. pylori and support the gastric mucosa [37, 50].

- Glutamine, an amino acid, has been shown to help improve the integrity of the gut lining [51].

Cancer Prevention

While gastric cancer is rare in gastritis (at an incidence of 0.1% annually for people with gastritis,) it is still helpful to know what methods may be used to reduce the incidence of gastric cancer:

- Both COX (cyclooxygenase inhibitors) and NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) may be used to help slow the progression of gastric cancer, but supporting evidence is limited [1, 52, 53].

- The Chinese herbal medicine, Moludoan, was shown in a randomized clinical trial to improve precancerous gastric tissue after six months [54].

- Surgery such as endoscopic resection may be done to remove precancerous lesions and to treat early adenocarcinoma (cancer that occurs in glandular cells) [55].

- There is evidence to suggest that low doses of Vitamins A, C, and E may reduce the risk of gastric carcinoma by a third [56].

Knowing the Cause and Customizing Treatment

If you are diagnosed with atrophic gastritis, it’s important to discover the root cause. Addressing any other issues such as anemia or micronutrient deficiencies that may lead to neurological issues, and decreasing the risk of gastric cancer, will be essential.

If you would like more personalized guidance on your path to healing, request an appointment at my functional medicine center.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.➕ References

- Raza M, Bhatt H. Atrophic Gastritis. 2020 Dec 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 33085422.

- WHITESIDE MG, MOLLIN DL, COGHILL NF, WILLIAMS AW, ANDERSON B. THE ABSORPTION OF RADIOACTIVE VITAMIN B12 AND THE SECRETION OF HYDROCHLORIC ACID IN PATIENTS WITH ATROPHIC GASTRITIS. Gut. 1964 Oct;5(5):385-99. doi: 10.1136/gut.5.5.385. PMID: 14218551; PMCID: PMC1552148.

- Lenti MV, Rugge M, Lahner E, Miceli E, Toh BH, Genta RM, De Block C, Hershko C, Di Sabatino A. Autoimmune gastritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Jul 9;6(1):56. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0187-8. PMID: 32647173.

- Annibale B, Esposito G, Lahner E. A current clinical overview of atrophic gastritis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Feb;14(2):93-102. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1718491. Epub 2020 Jan 24. PMID: 31951768.

- Carabotti M, Lahner E, Esposito G, Sacchi MC, Severi C, Annibale B. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms in autoimmune gastritis: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Jan;96(1):e5784. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005784. PMID: 28072728; PMCID: PMC5228688.

- Miceli E, Lenti MV, Padula D, Luinetti O, Vattiato C, Monti CM, Di Stefano M, Corazza GR. Common features of patients with autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jul;10(7):812-4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.018. Epub 2012 Mar 2. PMID: 22387252.

- O’Connor A, O’Moráin C. Digestive function of the stomach. Dig Dis. 2014;32(3):186-91. doi: 10.1159/000357848. Epub 2014 Apr 10. PMID: 24732181.

- Ramsay PT, Carr A. Gastric acid and digestive physiology. Surg Clin North Am. 2011 Oct;91(5):977-82. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.06.010. PMID: 21889024.

- Massironi S, Zilli A, Elvevi A, Invernizzi P. The changing face of chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis: an updated comprehensive perspective. Autoimmun Rev. 2019 Mar;18(3):215-222. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.08.011. Epub 2019 Jan 11. PMID: 30639639.

- Song H, Zhu J, Lu D. Long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and the development of gastric pre-malignant lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Dec 2;(12):CD010623. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010623.pub2. PMID: 25464111.

- Li Z, Wu C, Li L, Wang Z, Xie H, He X, Feng J. Effect of long-term proton pump inhibitor administration on gastric mucosal atrophy: A meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jul-Aug;23(4):222-228. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_573_16. PMID: 28721975; PMCID: PMC5539675.

- Minalyan A, Benhammou JN, Artashesyan A, Lewis MS, Pisegna JR. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis: current perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb 7;10:19-27. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S109123. PMID: 28223833; PMCID: PMC5304992.

- Nagasawa S, Azuma T, Motani H, Sato Y, Hayakawa M, Yajima D, Kobayashi K, Ootsuka K, Iwase H. Detection of Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) DNA in digestive systems from cadavers by real-time PCR. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009 Apr;11 Suppl 1:S458-9. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.03.001. Epub 2009 May 1. PMID: 19410495.

- Nagasawa S, Azuma T, Motani H, Sato Y, Hayakawa M, Yajima D, Kobayashi K, Ootsuka K, Iwase H. Detection of Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori) DNA in digestive systems from cadavers by real-time PCR. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2009 Apr;11 Suppl 1:S458-9. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.03.001. Epub 2009 May 1. PMID: 19410495.

- Waldum HL, Sørdal ØF, Mjønes PG. The Enterochromaffin-like [ECL] Cell-Central in Gastric Physiology and Pathology. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 May 17;20(10):2444. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102444. PMID: 31108898; PMCID: PMC6567877.

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomach-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- De Block CE, De Leeuw IH, Van Gaal LF. Autoimmune gastritis in type 1 diabetes: a clinically oriented review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Feb;93(2):363-71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2134. Epub 2007 Nov 20. PMID: 18029461.

- De Block CE, De Leeuw IH, Bogers JJ, Pelckmans PA, Ieven MM, Van Marck EA, Van Acker KL, Van Gaal LF. Autoimmune gastropathy in type 1 diabetic patients with parietal cell antibodies: histological and clinical findings. Diabetes Care. 2003 Jan;26(1):82-8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.82. PMID: 12502662.

- Lahner E, Annibale B. Pernicious anemia: new insights from a gastroenterological point of view. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Nov 7;15(41):5121-8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5121. PMID: 19891010; PMCID: PMC2773890.

- Sterzl I, Hrdá P, Matucha P, Čeřovská J, Zamrazil V. Anti-Helicobacter Pylori, anti-thyroid peroxidase, anti-thyroglobulin and anti-gastric parietal cells antibodies in Czech population. Physiol Res. 2008;57 Suppl 1:S135-S141. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931498. Epub 2008 Feb 13. PMID: 18271683.

- Gillberg R, Kastrup W, Mobacken H, Stockbrügger R, Ahren C. Gastric morphology and function in dermatitis herpetiformis and in coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985 Mar;20(2):133-40. doi: 10.3109/00365528509089645. PMID: 3992169.

- Kang MS, Park DI, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI. [Bamboo joint-like appearance of stomach in Korean patients with Crohn’s disease]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006 Dec;48(6):395-400. Korean. PMID: 17189922.

- Akiyama T, Kishimoto S, Miyaji K. Gastric acid secretion, serum gastrin and parietal cell histology in hyperthyroidism. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1982;17(1):42-9. doi: 10.1007/BF02774760. PMID: 7075932.

- Sugaya T, Sakai H, Sugiyama T, Imai K. [Atrophic gastritis in Sjögren’s syndrome]. Nihon Rinsho. 1995 Oct;53(10):2540-4. Japanese. PMID: 8531370.

- Tozzoli R, Kodermaz G, Perosa AR, Tampoia M, Zucano A, Antico A, Bizzaro N. Autoantibodies to parietal cells as predictors of atrophic body gastritis: a five-year prospective study in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010 Dec;10(2):80-3. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.08.006. Epub 2010 Aug 6. PMID: 20696284.

- Miceli E, Vanoli A, Lenti MV, Klersy C, Di Stefano M, Luinetti O, Caccia Dominioni C, Pisati M, Staiani M, Gentile A, Capuano F, Arpa G, Paulli M, Corazza GR, Di Sabatino A. Natural history of autoimmune atrophic gastritis: a prospective, single centre, long-term experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Dec;50(11-12):1172-1180. doi: 10.1111/apt.15540. Epub 2019 Oct 17. PMID: 31621927.

- Kong YJ, Yi HG, Dai JC, Wei MX. Histological changes of gastric mucosa after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5903-11. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5903. PMID: 24914352; PMCID: PMC4024801.

- Hirschl AM, Rotter ML. Amoxicillin for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol. 1996 Nov;31 Suppl 9:44-7. PMID: 8959518.

- Ierardi E, Losurdo G, Fortezza RF, Principi M, Barone M, Leo AD. Optimizing proton pump inhibitors in Helicobacter pylori treatment: Old and new tricks to improve effectiveness. World J Gastroenterol. 2019 Sep 14;25(34):5097-5104. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i34.5097. PMID: 31558859; PMCID: PMC6747288.

- Krakowka S, Eaton KA, Leunk RD. Antimicrobial therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection in gnotobiotic piglets. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998 Jul;42(7):1549-54. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1549. PMID: 9660981; PMCID: PMC105643.

- Feng JR, Wang F, Qiu X, McFarland LV, Chen PF, Zhou R, Liu J, Zhao Q, Li J. Efficacy and safety of probiotic-supplemented triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori in children: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017 Oct;73(10):1199-1208. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2291-6. Epub 2017 Jul 5. PMID: 28681177.

- Vale FF, Oleastro M. Overview of the phytomedicine approaches against Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 May 21;20(19):5594-609. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5594. PMID: 24914319; PMCID: PMC4024768.

- Lin S, Gao T, Sun C, Jia M, Liu C, Ma X, Ma A. Association of dietary patterns and endoscopic gastric mucosal atrophy in an adult Chinese population. Sci Rep. 2019 Nov 12;9(1):16567. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52951-7. PMID: 31719557; PMCID: PMC6851133.

- Li Y, Su Z, Li P, Li Y, Johnson N, Zhang Q, Du S, Zhao H, Li K, Zhang C, Ding X. Association of Symptoms with Eating Habits and Food Preferences in Chronic Gastritis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020 Jul 9;2020:5197201. doi: 10.1155/2020/5197201. PMID: 32695209; PMCID: PMC7368216.

- Lin HP, Wang YP, Chia JS, Chiang CP, Sun A. Modulation of serum gastric parietal cell antibody level by levamisole and vitamin B12 in oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2011 Jan;17(1):95-101. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01711.x. PMID: 20659263.

- Berlin H, Berlin R, Brante G. Oral treatment of pernicious anemia with high doses of vitamin B12 without intrinsic factor. Acta Med Scand. 1968 Oct;184(4):247-58. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1968.tb02452.x. PMID: 5751528.

- Massironi S, Cavalcoli F, Rossi RE, Conte D, Spampatti MP, Ciafardini C, Verga U, Beck-Peccoz P, Peracchi M. Chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis associated with primary hyperparathyroidism: a transversal prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013 Apr 15;168(5):755-61. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-1067. PMID: 23447517.

- Aranow C. Vitamin D and the immune system. J Investig Med. 2011 Aug;59(6):881-6. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e31821b8755. PMID: 21527855; PMCID: PMC3166406.

- Shi X, Zhang J, Mo L, Shi J, Qin M, Huang X. Efficacy and safety of probiotics in eradicating Helicobacter pylori: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Apr;98(15):e15180. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015180. PMID: 30985706; PMCID: PMC6485819.

- Losurdo G, Cubisino R, Barone M, Principi M, Leandro G, Ierardi E, Di Leo A. Probiotic monotherapy and Helicobacter pylori eradication: A systematic review with pooled-data analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jan 7;24(1):139-149. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.139. PMID: 29358890; PMCID: PMC5757118.

- Lü M, Yu S, Deng J, Yan Q, Yang C, Xia G, Zhou X. Efficacy of Probiotic Supplementation Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Eradication: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS One. 2016 Oct 10;11(10):e0163743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163743. PMID: 27723762; PMCID: PMC5056761.

- Tong JL, Ran ZH, Shen J, Zhang CX, Xiao SD. Meta-analysis: the effect of supplementation with probiotics on eradication rates and adverse events during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Jan 15;25(2):155-68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03179.x. PMID: 17229240.

- Koga Y, Ohtsu T,

Kimura K, et al. Probiotic

L. gasseri strain (LG21) for

the upper gastrointestinal

tract acting through

improvement of indigenous

microbiota. BMJ Open Gastro

2019;6:e000314. doi:10.1136/

bmjgast-2019-000314 - Li S, Huang XL, Sui JZ, Chen SY, Xie YT, Deng Y, Wang J, Xie L, Li TJ, He Y, Peng QL, Qin X, Zeng ZY. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2014 Feb;173(2):153-61. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2220-3. Epub 2013 Dec 10. PMID: 24323343.

- Lu C, Sang J, He H, Wan X, Lin Y, Li L, Li Y, Yu C. Probiotic supplementation does not improve eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection compared to placebo based on standard therapy: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016 Mar 21;6:23522. doi: 10.1038/srep23522. PMID: 26997149; PMCID: PMC4800733.

- Koga Y, Ohtsu T, Kimura K, Asami Y. Probiotic L. gasseri strain (LG21) for the upper gastrointestinal tract acting through improvement of indigenous microbiota. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019 Aug 12;6(1):e000314. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2019-000314. PMID: 31523442; PMCID: PMC6711431.

- Karbasi A, Hossein Hosseini S, Shohrati M, Amini M, Najafian B. Effect of oral N-acetyl cysteine on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with dyspepsia. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2013 Mar;59(1):107-12. PMID: 23478248.

- Jang S, Bak EJ, Cha JH. N-acetylcysteine prevents the development of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. J Microbiol. 2017 May;55(5):396-402. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-7089-9. Epub 2017 Apr 29. PMID: 28455589.

- Huynh HQ, Couper RT, Tran CD, Moore L, Kelso R, Butler RN. N-acetylcysteine, a novel treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2004 Nov-Dec;49(11-12):1853-61. doi: 10.1007/s10620-004-9583-2. PMID: 15628716.

- Hirokawa K, Kawasaki H. Changes in glutathione in gastric mucosa of gastric ulcer patients. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1995 May;88(2):163-76. PMID: 7670848.

- Zhou Q, Verne ML, Fields JZ, Lefante JJ, Basra S, Salameh H, Verne GN. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of dietary glutamine supplements for postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2019 Jun;68(6):996-1002. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315136. Epub 2018 Aug 14. PMID: 30108163.

- Huang XZ, Chen Y, Wu J, Zhang X, Wu CC, Zhang CY, Sun SS, Chen WJ. Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use reduce gastric cancer risk: A dose-response meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017 Jan 17;8(3):4781-4795. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13591. PMID: 27902474; PMCID: PMC5354871.

- Wong BC, Zhang L, Ma JL, Pan KF, Li JY, Shen L, Liu WD, Feng GS, Zhang XD, Li J, Lu AP, Xia HH, Lam S, You WC. Effects of selective COX-2 inhibitor and Helicobacter pylori eradication on precancerous gastric lesions. Gut. 2012 Jun;61(6):812-8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300154. Epub 2011 Sep 13. PMID: 21917649.

- Tang XD, Zhou LY, Zhang ST, Xu YQ, Cui QC, Li L, Lu JJ, Li P, Lu F, Wang FY, Wang P, Bian LQ, Bian ZX. Randomized double-blind clinical trial of Moluodan () for the treatment of chronic atrophic gastritis with dysplasia. Chin J Integr Med. 2016 Jan;22(1):9-18. doi: 10.1007/s11655-015-2114-5. Epub 2015 Oct 1. PMID: 26424292.

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer. 2017 Jan;20(1):1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0622-4. Epub 2016 Jun 24. PMID: 27342689; PMCID: PMC5215069.

- Kong P, Cai Q, Geng Q, Wang J, Lan Y, Zhan Y, Xu D. Vitamin intake reduce the risk of gastric cancer: meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized and observational studies. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 30;9(12):e116060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116060. PMID: 25549091; PMCID: PMC4280145.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!