How to Identify and Treat Laryngopharyngeal Reflux (LPR)

Symptoms, Causes, Testing, and Treatment for LPR or ‘Silent Reflux’

- LPR Basics|

- LPR Symptoms|

- LPR Causes|

- LPR Testing|

- LPR Treatment: A Hierarchical Approach|

- LPR Diet|

- Conventional Treatment for LPR|

- Recommended Products|

When we hear the word “reflux”, we tend to think of heartburn. But one common reflux disorder, laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (LPR), defies this standard concept. In fact, LPR is sometimes referred to as “silent reflux”, given that symptoms may either go unnoticed or not be easily associated with reflux.

Even among experts, LPR is not very well understood. Standard tests and criteria for diagnosis have not been established, epidemiological studies are lacking, and patients vary widely when it comes to symptoms and treatment response [1].

But none of this means that LPR can’t be treated. The lack of consensus when it comes to diagnosis and treatment reinforces the need to take a personalized and hierarchical treatment approach. In other words, take it one step at a time, and see what works for you (and what doesn’t).

This article will guide you through that process and provide an overview of what we know about the symptoms and causes of this condition.

Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Basics

What is LPR, and how does it differ from the better understood gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)?

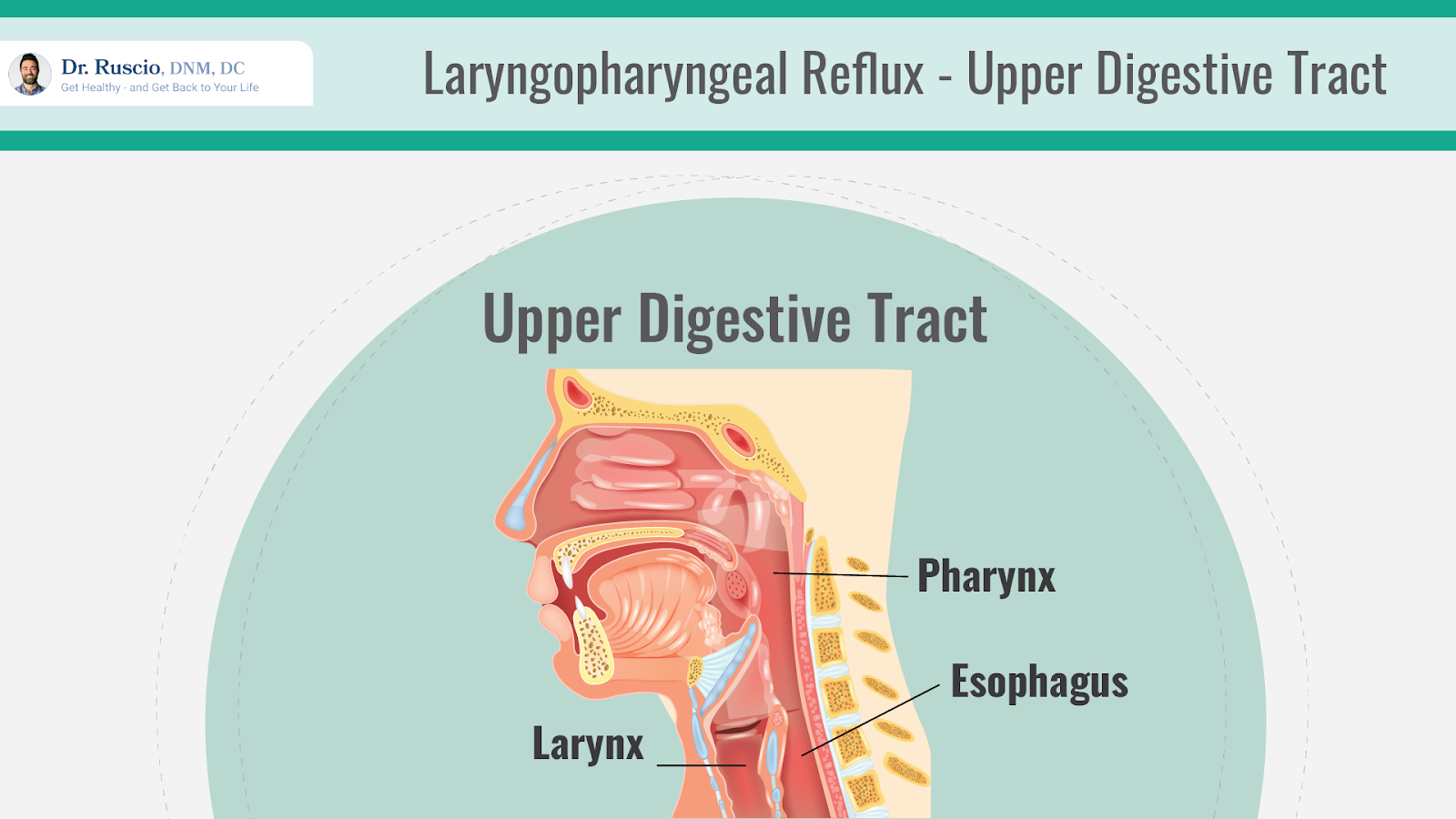

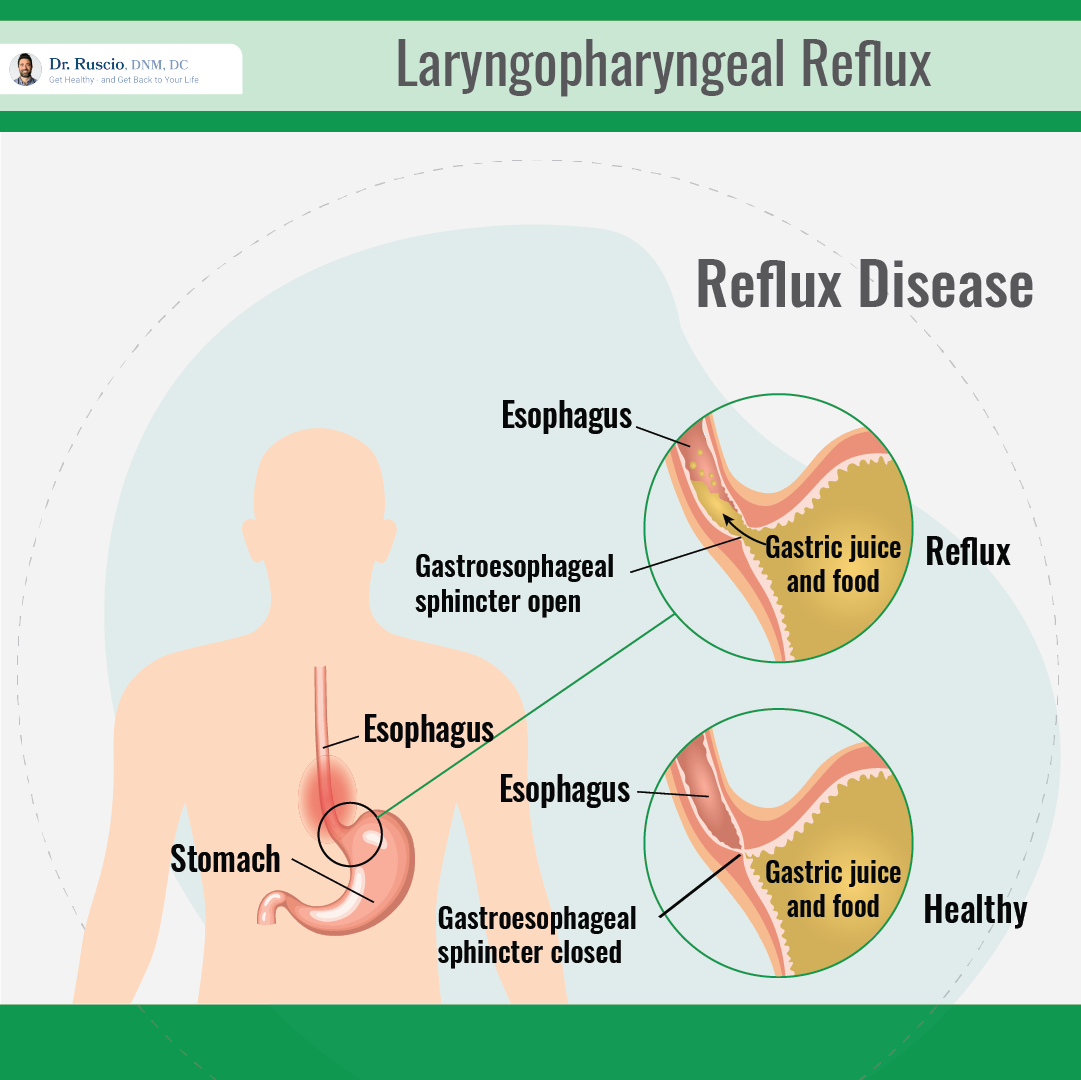

In the case of GERD, contents of the stomach come back up into the esophagus (a tube that connects the stomach to the throat) and create the symptoms we tend to associate with acid reflux, like heartburn.

With LPR, stomach contents travel past the esophagus and into the larynx (voice box) and pharynx (the throat). This leads to symptoms that are often different from GERD and can be difficult to pinpoint.

Symptoms of LPR

Symptoms of LPR vary but may include any of the following [2]:

- Hoarseness

- Frequent throat clearing

- Sore throat or throat irritation

- Heartburn

- Chronic cough

- Globus pharyngeus (persistent feeling of a lump in the throat)

- Dysphagia (trouble swallowing)

- Regurgitation

- Postnasal drip

For most people, LPR symptoms are uncomfortable but not severe. However, if left untreated, LPR may damage the vocal cords or lead to vocal injury [2]. LPR symptoms may also be an indication that something else is amiss within the digestive system and should therefore be investigated.

What Causes LPR?

The standard theory of LPR is that stomach contents including stomach acid and pepsin (a digestive enzyme) travel up the esophagus and all the way into the larynx. While we have various barriers and mechanisms in place that should keep reflux from getting to the throat, like the lower esophageal sphincter, any kind of barrier dysfunction can allow these contents to pass through, leading to symptoms [2].

An alternative explanation for LPR is referred to as “reflex theory” (as opposed to reflux theory, described above). Reflex theory suggests that reflux and acid in the lower esophagus (GERD) can cause laryngeal symptoms — without directly reaching the larynx — through a reflex involving the vagus nerve [3].

Causes and contributing factors may include:

- GERD [4]

- Low esophageal motility (esophageal contractions that should move food towards the stomach are weak) [5]

- Sleep apnea [6]

- Hiatal hernia (when part of the stomach pushes up into the chest) [7]

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [8, 9]

- H. pylori infection [10] (although some research suggests that H. pylori may actually be protective when it comes to reflux [11])

- High levels of pepsin (a stomach enzyme) [12]

- Consumption of certain foods, including acidic foods, high-fiber diets, alcohol, caffeine (although some research refutes this [13]), sugary beverages, fermented foods, and gluten [14, 15, 16, 17]

LPR, GERD, and IBS: What’s the Connection?

While research is inconclusive regarding the exact connections between LPR, GERD, and IBS, the overlap between symptoms of these conditions warrants the investigation of overlap in causes as well.

For example, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) often underlies IBS, and many patients with IBS also have reflux or LPR [9, 18, 19]. Therefore, gut health abnormalities or imbalances like SIBO are worthy of exploration in cases of laryngopharyngeal reflux.

LPR Testing

Several different diagnostic techniques may help to diagnose LPR. These include:

- Endoscopy or specialized endoscopic procedures

- Laryngoscopy

- pH probe or pH monitoring

- Mucosal integrity tests

- Manometry

Diagnostic criteria and testing methods are not agreed upon when it comes to LPR. Diagnostic techniques favored by gastroenterologists may also differ from those used by otolaryngologists (ear, nose, and throat specialists).

LPR Treatment: A Hierarchical Approach

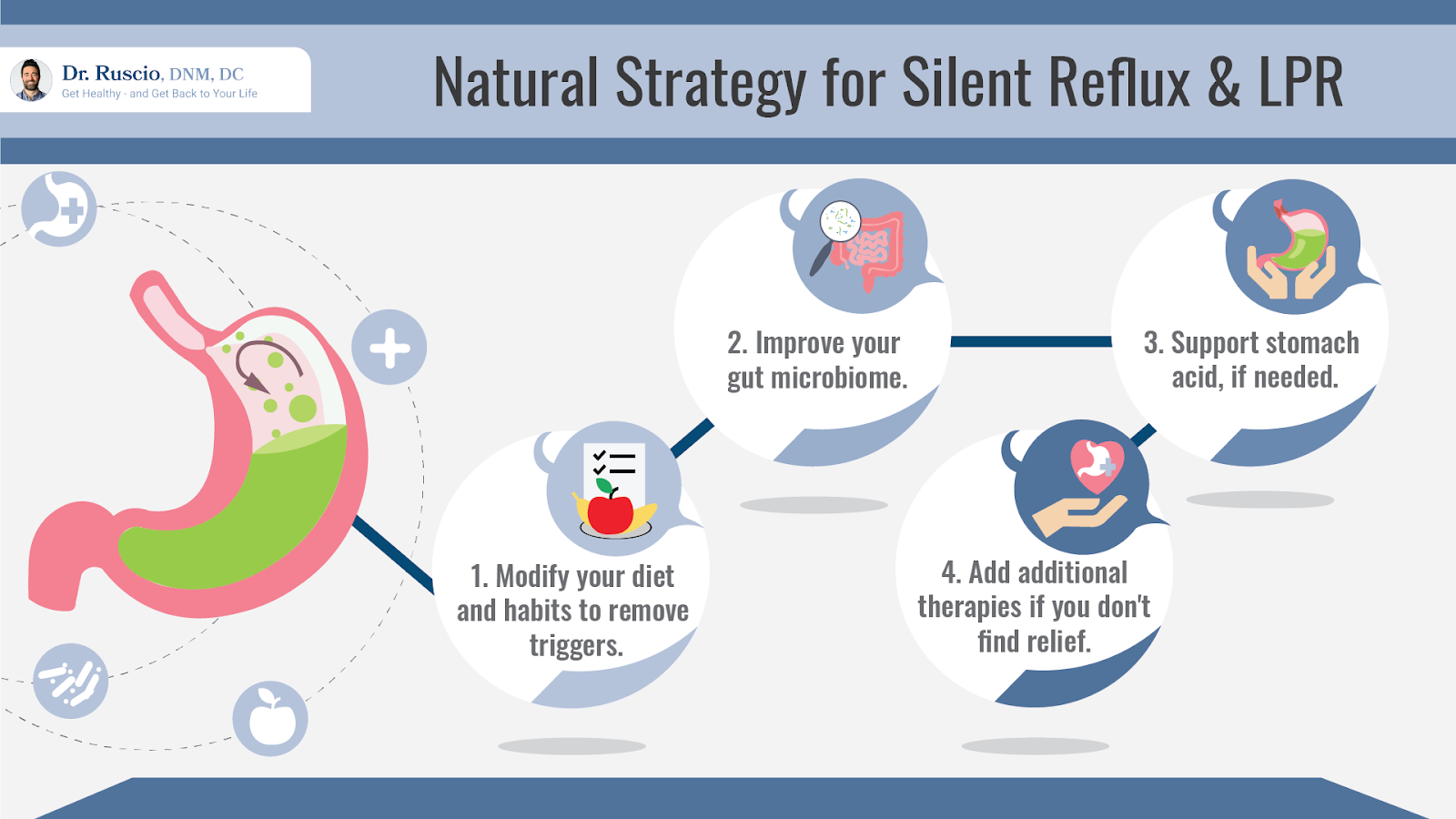

Treatments for laryngopharyngeal reflux may include specialized diets, identifying and treating gut health imbalances, the use of natural or pharmaceutical agents to lower stomach acid, and, in some cases, surgery.

Research is limited when it comes to LPR treatment. For conditions such as LPR where underlying causes, contributing factors, and treatment responses vary widely, I generally recommend following a pyramid-style, hierarchical approach.

Determining your ideal therapeutic diet comes first. In many cases, this is enough to resolve symptoms. If not, you can move on to the next step, which is investigating and treating any imbalances within the gut. Continue one step at a time, monitoring your response to any new treatments or modifications.

Step 1: Find Your Ideal Diet

Finding your ideal diet should be the first step when it comes to LPR treatment.

In many cases, finding the right diet is enough to resolve symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux. At a minimum, the right diet helps to establish a healthier foundation from which to approach other treatments.

A 2020 systematic review found that following a low-acid diet helped to reduce symptoms of LPR [20].

One observational study also found that a plant-based Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes whole foods, was more effective than proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in the treatment of LPR [21]. While this doesn’t mean that everyone with LPR needs to follow a low-acid or plant-based Mediterranean diet, it does speak to the power of diet therapy for this condition.

Research hasn’t identified one diet that works across the board for patients with LPR. However, as with other digestive conditions, an elimination diet can help you to determine which foods contribute to your symptoms.

Start With an Elimination Diet

Underlying food sensitivities can contribute to digestive disorders and chronic symptoms of all kinds, even if you eat a generally healthy diet. This is where an elimination diet comes in: Through a process of elimination and systematic reintroduction, you can determine which foods make you feel your best and which may lead to symptoms.

An elimination diet based on the Paleo diet is often a good starting point. The Paleo diet eliminates many common food triggers and allergens, including gluten and dairy.

- Consider whether there are any foods that you already know aggravate your symptoms, and eliminate these right away.

- Begin a 3-4 week elimination period in which you avoid common trigger foods. This may be based on a Paleo or Autoimmune Paleo diet framework.

- If this helps to resolve symptoms, begin a reintroduction period in which you add one eliminated item back into your diet at a time, monitoring your symptoms. This should help you to identify which foods you should continue to avoid and which ones you can tolerate. Do not reintroduce processed or sugary foods, which are not healthy for anyone.

- If the elimination period doesn’t help to resolve symptoms, consider a trial of a more specialized diet, such as a low FODMAP or low histamine diet (see below).

Some foods and drinks have been associated with LPR symptoms, and should ideally be avoided as part of your elimination diet. These include:

- Acidic foods (i.e. citrus, tomatoes) [14]

- Spicy foods [22]

- Oily foods [22]

- Fermented foods [16]

- Alcohol [14]

- Chocolate

- Coffee [14]

Low Histamine Diet

A low histamine diet may be helpful for some people with LPR and can be trialed if a standard elimination diet doesn’t provide relief. Histamine promotes acid production in the stomach (this is why histamine (H2) blockers are often recommended for acid reflux) and reduces the intake of foods that either contain histamine or cause the body to produce histamine may help to combat the problem.

Notably, although studies haven’t yet looked at the low histamine diet for LPR, the vast majority of individual foods that have been associated with LPR are high histamine or histamine-promoting foods. These include fermented foods, spicy foods, citrus fruits, tomatoes, chocolate, and alcohol.

Low FODMAP Diet

The low FODMAP diet is often recommended for SIBO and IBS and has been shown to significantly improve symptoms of both [23, 24, 25, 26]. As there’s a significant amount of overlap between these conditions and reflux disorders including LPR, a low FODMAP diet, which eliminates fermentable carbohydrates that feed excess gut bacteria, may be an effective treatment option.

Although research hasn’t looked at the low FODMAP diet for LPR specifically, studies have shown that low FODMAP diets can help to reduce reflux symptoms, including heartburn, for those with GERD [27].

The low FODMAP diet has also been shown to significantly reduce levels of acid-promoting histamine in the gut microbiome [28].

Other Dietary Strategies

Other dietary habits that have been shown to improve LPR symptoms include drinking alkaline water (a filter can be used to make alkaline water at home) and avoiding food and drinks for 2-3 hours before bed [22].

Step 2: Investigate and Treat Gut Health Imbalances

If diet alone doesn’t resolve symptoms, the next step is to look into possible gut health imbalances.

H. pylori infections may contribute to LPR in some cases and can be tested for [10].

Another possible culprit is SIBO. Although research hasn’t yet investigated a connection between SIBO and LPR, the increased gas pressure associated with SIBO may be a contributing factor. Overgrowths of certain kinds of bacteria can also lead to increased production of histamine, which promotes stomach acid. Treating SIBO may help to resolve symptoms of LPR and other chronic issues.

Taking probiotics to balance the gut microbiome may also be helpful. Although studies haven’t looked at the use of probiotics for laryngopharyngeal reflux specifically, several studies have shown improvements in symptoms of GERD with probiotic therapy [29].

Step 3: Consider Whether Stomach Acid Levels Could be Low

Although reflux disorders are typically associated with excess stomach acid, the opposite (low stomach acid) can also be problematic. The symptoms of excess stomach acid and insufficient stomach acid are similar, which can make things confusing.

The following table uses a few common signs and risk factors to help you determine whether you’re more likely to have low or high stomach acid levels.

| Low Stomach Acid | High Stomach Acid |

| Age (over 65) | Age (younger than 65) |

| Anemia or autoimmune disease | “Gnawing” stomach pain |

| Chronic use of painkillers or excessive coffee consumption | Family or personal history of gastritis or ulcers |

If low stomach acid is suspected, a trial of supplemental HCl (hydrochloric acid) may be recommended. The best way to do this is to try HCl for 2-3 weeks while monitoring your symptoms without making any other changes to your treatment or diet. This way, you’ll get a clear picture of whether it’s helping or making things worse.

Step 4: Try Natural Treatments for Stomach Acid Reduction.

There are a number of natural agents and supplements that can lower stomach acid and help with symptom relief. These can be used as part of a protocol that involves diet as a foundation and addresses underlying causes and imbalances.

Supplements that have been shown to help with reflux symptoms in LPR, GERD, or both include:

- Melatonin [30, 31]

- L-tryptophan (in combination with melatonin) [32]

- Sodium alginate [20]

- Prokinetic (gastrointestinal motility strengthening) herbal blends [20, 33]

Conventional Treatments for LPR

Conventional treatments for LPR include stomach-acid reducing medications and, in some cases, surgery.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

Proton pump inhibitors are a class of stomach acid-lowering medications that are often used to treat LPR, GERD, and ulcers. Common PPIs include omeprazole, esomeprazole, and rabeprazole.

However, research on the efficacy of PPIs for LPR is mixed. Two systematic reviews have concluded that PPIs are at least mildly more effective than placebos at treating LPR, especially when combined with diet and lifestyle changes [34, 35]. Conversely, a separate systematic review concluded that there was no difference between PPIs and placebo treatment for LPR [36].

H2 Blockers

H2 blockers are a group of medications that help to reduce stomach acid by blocking the action of histamine (which is involved in acid production) in the stomach. Studies haven’t yet examined the use of H2 blockers for LPR, but two systematic reviews have found them to be effective in the treatment of GERD [37, 38].

Surgery (Fundoplication)

Fundoplication surgery is sometimes recommended for patients with LPR or GERD. The procedure involves wrapping part of the stomach around part of the esophagus in order to block the flow of acid and other stomach contents to (or past) the esophagus. Evidence for the effectiveness of this procedure for LPR is inconclusive, according to a 2019 systematic review of 34 observational studies [39].

Are PPIs Harmful?

The use of PPIs is somewhat controversial and often discouraged in the functional medicine community, based on research associating proton pump inhibitor therapy with an increased risk of heart disease, cardiovascular events including heart attacks, SIBO, certain kinds of infections (such as C. difficile), and pneumonia [40, 41, 42, 43].

All of these risks are associated with the long-term use of PPIs. Short-term use, on the other hand, has not been associated with these risks and can be helpful in certain cases.

For example, if you have a stomach ulcer and symptoms of LPR, temporary use of PPIs can help to get your acid levels under control and treat your ulcer while you address diet, lifestyle, and any gut health imbalances that may be contributing to acid production and symptoms.

Take LPR Treatment One Step at a Time

There is a significant amount of overlap between laryngopharyngeal reflux and other digestive disorders, including GERD and IBS. As with these other conditions, the best approach is individualized, hierarchical, and built on a foundation of a healthy diet and a healthy gut.

For a more comprehensive guide to healing your gut and your symptoms, check out my book, Healthy Gut, Healthy You. For more personalized guidance, you can also request a consultation at my functional medicine center.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.➕ References

- Lechien JR, Akst LM, Hamdan AL, Schindler A, Karkos PD, Barillari MR, Calvo-Henriquez C, Crevier-Buchman L, Finck C, Eun YG, Saussez S, Vaezi MF. Evaluation and Management of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease: State of the Art Review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019 May;160(5):762-782. doi: 10.1177/0194599819827488. Epub 2019 Feb 12. PMID: 30744489.

- Brown J, Shermetaro C. Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. [Updated 2021 Jan 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519548/

- Barrett CM, Patel D, Vaezi MF. Laryngopharyngeal Reflux and Atypical Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2020 Apr;30(2):361-376. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2019.12.004. Epub 2020 Jan 22. PMID: 32146951.

- Katzka DA, Kahrilas PJ. Advances in the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. BMJ. 2020 Nov 23;371:m3786. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3786. PMID: 33229333.

- Passaretti S, Mazzoleni G, Vailati C, Testoni PA. Oropharyngeal acid reflux and motility abnormalities of the proximal esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Oct 28;22(40):8991-8998. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8991. PMID: 27833390; PMCID: PMC5083804.

- Magliulo G, Iannella G, Polimeni A, De Vincentiis M, Meccariello G, Gulotta G, Pasquariello B, Montevecchi F, De Vito A, D’Agostino G, Gobbi R, Cammaroto G, Vicini C. Laryngopharyngeal reflux in obstructive sleep apnoea patients: Literature review and meta-analysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018 Nov-Dec;39(6):776-780. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.09.006. Epub 2018 Sep 12. PMID: 30224217.

- Saruç M, Aksoy EA, Vardereli E, Karaaslan M, Ciçek B, Ince U, Oz F, Tözün N. Risk factors for laryngopharyngeal reflux. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Apr;269(4):1189-94. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1905-3. Epub 2011 Dec 30. PMID: 22207531.

- Pendleton H, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Olsson R, Thorsson O, Hammar O, Jannert M, Ohlsson B. Posterior laryngitis: a disease with different aetiologies affecting health-related quality of life: a prospective case-control study. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2013 Sep 9;13(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6815-13-11. PMID: 24015952; PMCID: PMC3846677.

- Kamani T, Penney S, Mitra I, Pothula V. The prevalence of laryngopharyngeal reflux in the English population. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Oct;269(10):2219-25. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2028-1. Epub 2012 May 11. PMID: 22576243.

- Campbell R, Kilty SJ, Hutton B, Bonaparte JP. The Role of Helicobacter pylori in Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Feb;156(2):255-262. doi: 10.1177/0194599816676052. Epub 2016 Nov 1. PMID: 27803078.

- Lin D, Koskella B. Friend and foe: factors influencing the movement of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori along the parasitism-mutualism continuum. Evol Appl. 2015 Jan;8(1):9-22. doi: 10.1111/eva.12231. Epub 2014 Nov 20. PMID: 25667600; PMCID: PMC4310578.

- Jung AR, Kwon OE, Park JM, Dong SH, Jung SY, Lee YC, Eun YG. Association Between Pepsin in the Saliva and the Subjective Symptoms in Patients With Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. J Voice. 2019 Mar;33(2):150-154. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.10.015. Epub 2017 Nov 24. PMID: 29174850.

- Boekema PJ, Samsom M, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Coffee and gastrointestinal function: facts and fiction. A review. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;230:35-9. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025525. PMID: 10499460.

- Lechien JR, Bobin F, Mouawad F, Zelenik K, Calvo-Henriquez C, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Enver N, Nacci A, Barillari MR, Schindler A, Crevier-Buchman L, Hans S, Simeone V, Wlodarczyk E, Harmegnies B, Remacle M, Rodriguez A, Dequanter D, Eisendrath P, Dapri G, Finck C, Karkos P, Pendleton H, Ayad T, Muls V, Saussez S. Development of scores assessing the refluxogenic potential of diet of patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Dec;276(12):3389-3404. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05631-1. Epub 2019 Sep 12. PMID: 31515662.

- Lechien JR, Bobin F, Muls V, Horoi M, Thill MP, Dequanter D, Rodriguez A, Saussez S. Patients with acid, high-fat and low-protein diet have higher laryngopharyngeal reflux episodes at the impedance-pH monitoring. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Feb;277(2):511-520. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05711-2. Epub 2019 Nov 2. PMID: 31679054.

- Kesari SP , Chakraborty S , Sharma B . Evaluation of Risk Factors for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux among Sikkimese Population. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2017 Jan.-Mar.;15(57):29-34. PMID: 29446359.

- Volta U, Bardella MT, Calabrò A, Troncone R, Corazza GR; Study Group for Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. An Italian prospective multicenter survey on patients suspected of having non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC Med. 2014 May 23;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-85. PMID: 24885375; PMCID: PMC4053283.

- Nastaskin I, Mehdikhani E, Conklin J, Park S, Pimentel M. Studying the overlap between IBS and GERD: a systematic review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Dec;51(12):2113-20. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9306-y. Epub 2006 Nov 1. PMID: 17080246.

- Yarandi SS, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Mostajabi P, Malekzadeh R. Overlapping gastroesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: increased dysfunctional symptoms. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar 14;16(10):1232-8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1232. PMID: 20222167; PMCID: PMC2839176.

- Huestis MJ, Keefe KR, Kahn CI, Tracy LF, Levi JR. Alternatives to Acid Suppression Treatment for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2020 Oct;129(10):1030-1039. doi: 10.1177/0003489420922870. Epub 2020 May 25. PMID: 32449369.

- Zalvan CH, Hu S, Greenberg B, Geliebter J. A Comparison of Alkaline Water and Mediterranean Diet vs Proton Pump Inhibition for Treatment of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Oct 1;143(10):1023-1029. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1454. PMID: 28880991; PMCID: PMC5710251.

- Min C, Park B, Sim S, Choi HG. Dietary modification for laryngopharyngeal reflux: systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 2019 Feb;133(2):80-86. doi: 10.1017/S0022215118002256. Epub 2019 Jan 16. PMID: 30646967.

- Staudacher HM, Whelan K. The low FODMAP diet: recent advances in understanding its mechanisms and efficacy in IBS. Gut. 2017 Aug;66(8):1517-1527. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313750. Epub 2017 Jun 7. PMID: 28592442.

- Marsh A, Eslick EM, Eslick GD. Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2016 Apr;55(3):897-906. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0922-1. Epub 2015 May 17. PMID: 25982757.

- Schumann D, Klose P, Lauche R, Dobos G, Langhorst J, Cramer H. Low fermentable, oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyol diet in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2018 Jan;45:24-31. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.07.004. Epub 2017 Jul 13. PMID: 29129233.

- Altobelli E, Del Negro V, Angeletti PM, Latella G. Low-FODMAP Diet Improves Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017 Aug 26;9(9):940. doi: 10.3390/nu9090940. PMID: 28846594; PMCID: PMC5622700.

- Piche T, des Varannes SB, Sacher-Huvelin S, Holst JJ, Cuber JC, Galmiche JP. Colonic fermentation influences lower esophageal sphincter function in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2003 Apr;124(4):894-902. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50159. PMID: 12671885.

- McIntosh K, Reed DE, Schneider T, Dang F, Keshteli AH, De Palma G, Madsen K, Bercik P, Vanner S. FODMAPs alter symptoms and the metabolome of patients with IBS: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2017 Jul;66(7):1241-1251. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311339. Epub 2016 Mar 14. Erratum in: Gut. 2019 Jul;68(7):1342. PMID: 26976734.

- Cheng J, Ouwehand AC. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Probiotics: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2020 Jan 2;12(1):132. doi: 10.3390/nu12010132. PMID: 31906573; PMCID: PMC7019778.

- Kandil TS, Mousa AA, El-Gendy AA, Abbas AM. The potential therapeutic effect of melatonin in Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010 Jan 18;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-7. PMID: 20082715; PMCID: PMC2821302.

- Klupińska G, Wiśniewska-Jarosińska M, Harasiuk A, Chojnacki C, Stec-Michalska K, Błasiak J, Reiter RJ, Chojnacki J. Nocturnal secretion of melatonin in patients with upper digestive tract disorders. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006 Nov;57 Suppl 5:41-50. PMID: 17218759.

- Pereira Rde S. Regression of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms using dietary supplementation with melatonin, vitamins and aminoacids: comparison with omeprazole. J Pineal Res. 2006 Oct;41(3):195-200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00359.x. PMID: 16948779.

- Rösch W, Vinson B, Sassin I. A randomised clinical trial comparing the efficacy of a herbal preparation STW 5 with the prokinetic drug cisapride in patients with dysmotility type of functional dyspepsia. Z Gastroenterol. 2002 Jun;40(6):401-8. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32130. PMID: 12055663.

- Lechien JR, Saussez S, Schindler A, Karkos PD, Hamdan AL, Harmegnies B, De Marrez LG, Finck C, Journe F, Paesmans M, Vaezi MF. Clinical outcomes of laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2019 May;129(5):1174-1187. doi: 10.1002/lary.27591. Epub 2018 Dec 30. PMID: 30597577.

- Wei C. A meta-analysis for the role of proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Nov;273(11):3795-3801. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4142-y. Epub 2016 Jun 16. PMID: 27312992.

- Liu C, Wang H, Liu K. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors for the symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2016 Jul 4;49(7):e5149. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20165149. PMID: 27383119; PMCID: PMC4942224.

- Zhao F, Wang S, Liu L, Wang Y. Comparative effectiveness of histamine-2 receptor antagonists as short-term therapy for gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a network meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Oct;54(10):761-70. doi: 10.5414/CP202564. PMID: 27443665.

- Mattos ÂZ, Marchese GM, Fonseca BB, Kupski C, Machado MB. ANTISECRETORY TREATMENT FOR PEDIATRIC GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE – A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Arq Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;54(4):271-280. doi: 10.1590/S0004-2803.201700000-42. Epub 2017 Sep 21. PMID: 28954042.

- Lechien JR, Dapri G, Dequanter D, et al. Surgical Treatment for Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(7):655–666. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0315

- Shi W, Yan L, Yang J, Yu M. Ethnic variance on long term clinical outcomes of concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel in patients with stent implantation: A PRISMA-complaint systematic review with meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Feb 12;100(6):e24366. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024366. PMID: 33578533; PMCID: PMC7886473.

- Shiraev TP, Bullen A. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review. Heart Lung Circ. 2018 Apr;27(4):443-450. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.10.020. Epub 2017 Nov 20. PMID: 29233498.

- Jessica Devitt, MD Corey Lyon, DO Sarah Beth Swanson, MD Kristen DeSanto, MSLS, MS, RD. What are the risks of long-term PPI use for GERD symptoms in patients > 65 years? MDedge, J Fam Pract. 2019 April. 68(3):E18-E19

- Su T, Lai S, Lee A, He X, Chen S. Meta-analysis: proton pump inhibitors moderately increase the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jan;53(1):27-36. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1371-9. Epub 2017 Aug 2. PMID: 28770351.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!