Ulcerative Colitis vs. Crohn’s: How These Conditions Compare

Comparing IBD Symptoms, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Treatments

- Ulcerative Colitis vs. Crohn's Disease|

- Symptoms|

- Causes|

- Diagnosis|

- Treatment Options|

- Recommended Products|

Download this Episode (right click link and ‘Save As’)

When you suffer from chronic digestive issues, it can be hard to know what’s causing the problem. Two of the most common gut diseases many get tested for are ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease because both diseases often have similar symptoms. Both are also inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

Since they are similar in many ways, people often confuse the two diseases. It can be difficult to know exactly why testing for ulcerative colitis vs Crohn’s might be helpful or even needed.

In this article, we will take away the confusion and give you an overview of the main similarities and differences in symptoms, testing, and treatment between the two diseases.

What Is Inflammatory Bowel Disease?

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term used to describe both Crohn’s and colitis. IBD differs from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), although there is often overlap in causes, symptoms, and treatments.

Inflammatory bowel diseases are diagnosable through imaging, and irritable bowel syndrome is characterized by a group of symptoms that do not show any definitive disease in testing.

Ulcerative Colitis vs. Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are both inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract, but they affect different parts of the system.

- Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus.

- Ulcerative colitis only affects the lining of the colon (large intestine), usually starting at the rectum and moving up, sometimes affecting the entire colon. Quick tip: You can think of colitis as colon plus itis (inflammation) which means inflammation of the colon.

Ulcerative colitis is the most common form of IBD worldwide and is more common in adults. Crohn’s and colitis affect between 158 and 291 people per 1000,000 per year [1].

Symptoms of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

The symptoms of Crohn’s and colitis are often similar and include both digestive and non-digestive symptoms.

Symptoms of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s may include [2, 3, 4]:

- Gas, cramping, and bloating

- Diarrhea (constipation is not as common)

- Urgent or frequent bowel movements

- Abdominal pain

- Weight loss

- Brain fog

- Fatigue

- Eye inflammation

- Skin issues

- Arthritis or joint pain

- Hemorrhoids

Symptoms, especially the digestive symptoms, tend to flare-up and recede throughout the course of both diseases. Many people also struggle with brain fog and fatigue, which can flare, but often these two symptoms linger even in between digestive flares.

Key Differences in Symptoms of Ulcerative Colitis vs. Crohn’s Disease

Although abdominal pain is a common symptom of both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, one of the key factors that differentiates the two conditions is the location of the pain [2].

Crohn’s: Abdominal pain is more often in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen and in the upper abdomen (all along the GI tract).

Colitis: People more often experience general lower abdominal pain.

Since the location of the pain is important, noting the location of your abdominal pain can be helpful when you are tracking your symptoms.

There are also a few non-digestive symptoms that are seen more often in Crohn’s disease and not ulcerative colitis such as gallstones and issues with the bile ducts as well as kidneys.

This table of symptoms might help you see the similarities and differences. Symptoms that are common in both diseases are in bold.

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

| Abdominal Symptoms | General lower abdominal pain Bloody diarrhea, with or without mucus Urgent bowel movements Cramping, rectal pain | Right lower quadrant abdominal pain (colon pain) Upper abdominal pain Diarrhea that may include mucus and blood Gas, cramping, and bloating |

| General Non-Abdominal Symptoms | Malaise Weight loss Fever Arthritis of the spine, sacrum, knees, ankles, hips, wrists, or elbows Fatigue Brain fog | Fever Weight loss Anemia Fatigue Brain fog Appetite loss Arthritis of the spine, sacrum, knees, ankles, hips, wrists, or elbows Malabsorption |

| Skin, Eyes, and Mouth | Eye inflammation causing redness, swelling, irritation, or blurred vision Painful nodules under the skin or ulcers on the skin | Eye inflammation causing redness, swelling, irritation, or blurred vision Inflammation of the mouth and lips Canker sores Painful nodules under the skin or ulcers on the skin |

| Kidney & Liver Symptoms | Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts | Buildup of fat in the liver (liver disease) Gallstones Inflammation of the bile ducts that carry bile from the liver and gallbladder to the small intestine Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts Kidney stones or swelling |

| Additional Complications | Colorectal cancer (co-occurring) Hemorrhoids | Urinary tract infectionsBlood clots Perineal skin tags, ulcers, fistulas, scarring, or abscesses Colorectal cancer (co-occurring) Hemorrhoids |

Causes of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

There are multiple contributing risk factors that can lead to ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s. Evidence does suggest that both are associated with an inappropriate immune response, which can arise from many different environmental factors, gut microbiome imbalance, as well as genetics [1].

The body creates temporary inflammation as part of a normal immune system response to threats and foreigners that may cause harm. An inappropriate immune response occurs when the immune system attacks something that is probably not harmful or overreacts to a possible pathogen. This creates unnecessary or excessive inflammation that can become chronic inflammation.

For example, in addition to toxins and infections, the immune system may attack food particles, beneficial gut bacteria, and, in the case of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, the lining of the digestive tract [1].

What might be causing the inflammation of the digestive tract and an inappropriate immune response?

Some of the contributing factors in IBD are:

SIBO

A 2019 meta analysis concluded that incidence of SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) was higher in people with IBD compared to people without IBD [5]. SIBO is an abnormal increase in the bacteria in the small intestine.

Leaky Gut

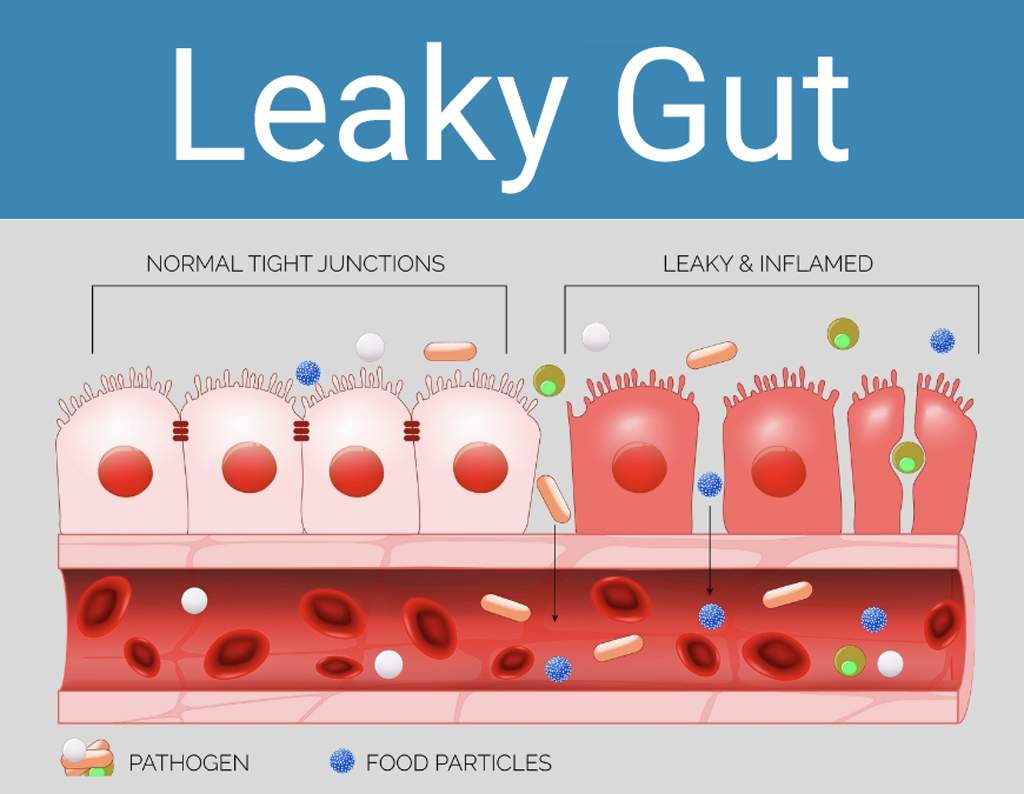

One systematic review of 47 observational studies found that IBD is one of the chronic conditions most strongly associated with increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) [6, 7].

Leaky gut is a loosening of the tight junctions between the cells that line your small intestine, which are supposed to prevent foreign molecules from getting into the bloodstream. When the junctions separate, large molecules such as undigested food particles and bacterial fragments enter into the bloodstream. The immune system attacks those molecules, which can cause inflammation throughout the body, including in the GI tract.

What exactly causes leaky gut in any one person can be different and usually includes a mix of environmental factors and genetics. Some examples include:

- Processed foods: Certain components of processed foods, such as emulsifiers (which help packaged foods bind together and not separate) like cellulose gum, other additives and artificial sweeteners may contribute to leaky gut [8, 9].

- Environment in early life: Studies have shown that antibiotic use early in life may increase the risk of developing IBD [10, 11]. A 2017 meta analysis of the medical literature also found that rates of IBD were higher in people who were not breastfed as babies [12].

Here are a few other potential causes of or contributing factors to IBD:

Diagnostic Testing

Tests for IBD may include:

- Stool tests and scans to rule out other conditions

- Blood tests such as C-reactive protein to measure inflammation levels

- P-ANCA and ASCA antibody tests to distinguish between Crohn’s and colitis.

How to Treat Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

For both Crohn’s and colitis, the first-line of conventional treatment with a gastroenterologist tends to focus on:

- Decreasing inflammation such as with oral mesalamine for Crohn’s and sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylates in colitis

- Using immunosuppressants (biologics) such as Remicade (infliximab) and Humeria (adalimumab) for both conditions

While many treatment options focus on reducing inflammation for symptom relief, it is also important to determine the root cause of the chronic inflammation. Discovering and treating the root cause can lead to fewer symptoms and minimal flare-ups. The root cause of inflammation is varied and may include toxins in the environment, any possible intestinal microbes, and foods that cause inflammation in your gastrointestinal tract.

Here are some of the main treatment foundations for IBD:

- Eating an anti-inflammatory diet

- Supporting the gut with probiotics

- Lifestyle changes to reduce stress

Anti-Inflammatory Diet

There is promising research about treating inflammatory bowel disease in general with an anti-inflammatory diet [16, 17, 18]. An anti-inflammatory diet helps heal the gut (including helping to heal the ulcers commonly found in Crohn’s disease) and thus improve IBD symptoms by removing foods that have compounds in them that are inflammatory to most people.

There are a few different kinds of anti-inflammatory diets that may be helpful for IBD, including the Paleo diet and the low FODMAP diet. For stubborn cases, a supplemental elemental diet for a period of 2-3 weeks can also provide rapid healing and symptom relief. Here’s a bit more information about these dietary strategies:

Paleo Diet

Many people try a Paleo diet to resolve IBD. The Paleo diet reduces inflammation by removing the most common inflammatory foods such as grains, dairy, vegetable oils, and legumes. When you reduce your intake of foods that may inflame the gut, your gut can start to heal.

Foods that are avoided on a Paleo diet include those that are generally inflammatory, such as processed foods and sugar, and other foods that are often inflammatory to an individual based on their sensitivities and immune system response. Gluten, dairy, and legumes (beans) tend to be among the most common food sensitivities.

The Autoimmune Paleo Diet (AIP), a more restrictive version of the Paleo diet which removes additional foods like eggs and nightshades, has been shown to help with both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease [16, 17].

If a standard Paleo diet helps somewhat, but not enough, you may want to try the AIP diet next.

I recommend trying a Paleo diet if:

- You are currently eating a diet high in inflammatory foods, and;

- You do not have any other conditions that you know require a more specialized diet.

Low-FODMAP Diet

A systematic review of 12 clinical trials found the low-FODMAP diet is an effective treatment for IBD. It can help reduce abdominal symptoms such as diarrhea, bloating, abdominal cramping, and pain, as well as non-abdominal symptoms like brain fog and fatigue [19, 20, 21].

A low-FODMAP diet removes foods that have certain carbohydrates that may feed pathogenic bacteria or cause a bacterial overgrowth, where certain bacteria feed on these carbohydrates and ferment them (fermentation creates gas and is one reason high-FODMAP foods cause abdominal bloating and pain).

Foods typically removed in a low-FODMAP diet are cruciferous vegetables (ie, broccoli and cabbage); certain fruits like apricot, mango, apple, and avocado; legumes (ie, beans and lentils); some nuts such as cashews; dairy; grains (especially wheat); and some sweeteners (fructose and even “healthier” sweeteners like agave and xylitol).

I recommend trying a low-FODMAP diet if:

- You have already tried a Paleo diet and have not seen significant improvements, and;

- You have been diagnosed with or are suspected to have SIBO or IBS.

Elemental Diet

For some people, an anti-inflammatory diet is not enough to help, especially during a colitis or Crohn’s flare-up.

Sometimes, the gut needs to rest and heal more thoroughly, which can be done with two to three weeks on an elemental diet. This type of liquid diet is easily digestible, anti-inflammatory, and provides all of the nutrients you need. In my clinical experience, this is one of the most effective treatments for stubborn cases of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Many studies show the benefit of an elemental diet in inflammatory bowel disease, and the elemental diet alone has been shown to be as effective as anti-inflammatory drugs like prednisone in promoting remission of IBD [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32].

After using an elemental diet to reset your gut, you can then move on to a more sustainable, longer term anti-inflammatory diet.

I recommend trying an elemental diet if:

- You have tried various anti-inflammatory diets and symptoms have not improved;

- You are in the midst of an acute IBD flare and need a gut reset.

How Long Do I Need to Follow an Anti-Inflammatory Diet?

Some people often wonder if they will need to be on a specialized anti-inflammatory diet forever. This is different for every person and can be tested by using your anti-inflammatory diet as an elimination diet. Here, you’ll eliminate foods to see if your symptoms improve and then systematically re-introduce foods to discover what foods you are sensitive to.

Often, after having long-term remission of IBD you might want to test certain foods and see if they cause digestive upset. When doing this, you add in one food that was removed on your anti-inflammatory diet and then wait two days to see if any symptoms arise. If not, then you may add in another food and test again. If a food creates an increase in symptoms, you may need a bit more healing time, a more targeted gut microbiome treatment, or to just continue avoiding that food.

Generally, a diet that improves leaky gut and lowers gastrointestinal inflammation can help decrease symptoms of both colitis and Crohn’s, giving you a better quality of life. Over time, your diet will be unique to you and your healing.

Probiotics

There is a large body of research supporting using probiotics to maintain good gut health and decrease symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease.

- One systematic review found that probiotics, especially multiple strains taken together, were effective at putting active ulcerative colitis into remission [33].

- One study found probiotics to be as effective as the medication mesalamine in preventing the relapse of ulcerative colitis [34].

- A clinical trial found that the probiotic strain Saccharomyces boulardii led to a faster resolution of abdominal symptoms and improved the gut microbiome in IBD patients [35].

- In tests of c-reactive protein, probiotics generally are shown to lower levels of inflammation [36].

While many studies have found probiotics to be beneficial for IBD, one systematic review found moderate evidence that probiotics were no better than placebo at putting active Crohn’s disease into remission [33]. You can try probiotics to see if they help in your particular case.

Reducing Stress

Stress is a part of our everyday life and we know that high amounts of stress can affect our immune system and digestive system. In colitis, studies show that relaxation techniques such as breathwork can lead to significant improvements in symptoms, quality of life, and a decrease in inflammation [37, 38]. Relaxation has also been shown to help people with IBD ruminate less about pain and symptom flare-ups [38].

There are quite a few options for treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Here is a helpful overview of your options:

| Medications | To decrease inflammation, oral mesalamine is most often used for Crohn’s and sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylates are used for colitis. To address the inappropriate immune response, immunosuppressants (biologics) such as Remicade (infliximab) and Humeria (adalimumab) for both conditions. |

| Surgery | Used mainly in severe cases of ulcerative colitis and often include a colectomy such as ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA surgery). |

| Low-FODMAP Diet | Shown to be helpful in both colitis and Crohn’s in decreasing inflammation, resolving flare-ups, and improving quality of life. |

| Elemental Diet | Shown to be a powerful treatment for IBD, with some studies finding elemental diets to be as effective as or even more effective than corticosteroids and anti-inflammatory drugs for Crohn’s treatment. |

| Probiotics | Shown to help in putting an active colitis flare-up into remission, but research is inconclusive about how much probiotics help in Crohn’s. Unclear if probiotics reduces relapse rates in either disease. |

| Digestive Enzymes | Shown to help in IBD in general. Especially good support for using them for colitis. |

| Reducing Stress with Breathwork and Meditation | Helpful in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. |

Begin the Road to Symptom Relief

It is hard to live with chronic symptom flare-ups, and it can be overwhelming when you are in the process of figuring out exactly what illness you might have. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease symptoms also overlap with symptoms of IBS and other gastrointestinal conditions, making diagnosis difficult.

Take the information you learned from this article and track your symptoms, so you have information to share with your doctor to help with diagnosis. Then, get a treatment plan in place and start on your journey towards healing.

For more personalized help with healing your gut and IBD treatment options that are tailored to your specific situation, request an appointment at my functional medicine center.

Sponsored Resources

Hey everyone. You’ve probably heard the term electrolytes and that people, especially those on low carb diets or who practice intermittent fasting or extended fasting, or who exercise a lot and sweat need electrolytes because you lose both water and sodium when you sweat. So both need to be replaced to prevent muscle cramps, headaches, and energy dips. Where we tend to get this wrong is if we replace only the water. This kind of hearkens back to the high school coaches putting salt tabs in the water.

I really like Robb Wolf’s drink LMNT as a healthy alternative to sugar-laden electrolyte drinks. Each packet replaces essential electrolytes with no sugar, no coloring, no artificial ingredients or any other junk. I do use the LMNT electrolytes for a host of reasons, mainly because I work out a lot, sweat a lot, sauna a lot, as you know. Especially when I’m doing a fast, that’s a great way to take the edge off. You can claim your free LMNT sample packs at drinkLMNT.com/RUSCIO. You’ll only cover the cost of shipping. Check them out.

Hi everyone. After many requests, we’re very excited to announce we have two brand new flavors of our best-selling Elemental Heal. Elemental Heal, in case you haven’t heard of it, is our great-tasting meal replacement, hypoallergenic gut-healing formula. These formulations and flavors aren’t ones you’ll find anywhere else and better yet you do not need a doctor’s note to order or use them. In addition to our existing varieties, we now offer peach in the whey-free version and vanilla in the low-carb version. These have been through some serious taste tests so we really think you’re going to enjoy them.

Whether you’re using elemental heal as a morning shake meal replacement as a mini gut reset for a few days, or even using it exclusively for two to three weeks, we now have a formula that should fit your needs. If you go to DrRuscio.com and head to the store, we’re offering 15% OFF any one of our elemental heal formulas. This discount is limited to one per customer. Simply use code, TryElementalHeal at checkout, and you’ll get 15% OFF. Let us know what you think about the new flavors. We believe that you’ll find them to be not only great tasting but also really friendly on the gut and can help give you a boost in how you’re feeling.

➕ References

- Ranasinghe IR, Hsu R. Crohn Disease. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. PMID: 28613792

- Ranasinghe IR, Hsu R. Crohn Disease. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. PMID: 28613792

- Choi YS, Kim DS, Lee DH, Lee JB, Lee EJ, Lee SD, Song KH, Jung HJ. Clinical Characteristics and Incidence of Perianal Diseases in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Ann Coloproctol. 2018 Jun;34(3):138–143. http://dx.doi.org/10.3393/ac.2017.06.08 PMCID: PMC6046543

- Bolshinsky V, Church J. Management of Complex Anorectal and Perianal Crohn’s Disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019 Jul;32(4):255–260. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1683907 PMCID: PMC6606315

- Shah A, Morrison M, Burger D, Martin N, Rich J, Jones M, Koloski N, Walker MM, Talley NJ, Holtmann GJ. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019 Mar;49(6):624–635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apt.15133 PMID: 30735254

- Leech B, McIntyre E, Steel A, Sibbritt D. Risk factors associated with intestinal permeability in an adult population: A systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2019 Oct;73(10):e13385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13385 PMID: 31243854

- Honzawa Y, Nakase H, Matsuura M, Chiba T. Clinical significance of serum diamine oxidase activity in inflammatory bowel disease: Importance of evaluation of small intestinal permeability. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2011. p. E23–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21588 PMID: 21225906

- Lerner A, Matthias T. Changes in intestinal tight junction permeability associated with industrial food additives explain the rising incidence of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. Autoimmun Rev; 2015 Jun [cited 2021 May 27];14(6). PMID: 25676324

- Swidsinski A, Ung V, Sydora BC, Loening-Baucke V, Doerffel Y, Verstraelen H, Fedorak RN. Bacterial overgrowth and inflammation of small intestine after carboxymethylcellulose ingestion in genetically susceptible mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. Inflamm Bowel Dis; 2009 Mar;15(3). PMID: 18844217

- Zou Y, Wu L, Xu W, Zhou X, Ye K, Xiong H, Song C, Xie Y. Correlation between antibiotic use in childhood and subsequent inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar;55(3):301–311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2020.1737882 PMID: 32180472

- Shaw SY, Blanchard JF, Bernstein CN. Association between the use of antibiotics in the first year of life and pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Dec;105(12):2687–2692. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.398 PMID: 20940708

- , , , , , . Systematic review with meta-analysis: breastfeeding and the risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46: 780-789. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14291

- Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. Am J Gastroenterol; 2012 Oct;107(10). PMID: 22929759

- Pinto-Sanchez MI, Seiler CL, Santesso N, Alaedini A, Semrad C, Lee AR, Bercik P, Lebwohl B, Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Moayyedi P, Green PH, Verdu EF. Association Between Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology; 2020 Sep;159(3). PMID: 32416141

- Washington MK. Autoimmune liver disease: overlap and outliers. Mod Pathol. Mod Pathol; 2007 Feb;20 Suppl 1. PMID: 17486048

- Chandrasekaran A, Groven S, Lewis JD, Levy SS, Diamant C, Singh E, Konijeti GG. An Autoimmune Protocol Diet Improves Patient-Reported Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohns Colitis 360. 2019 Oct;1(3):otz019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/crocol/otz019 PMCID: PMC6892563

- Konijeti GG, Kim N, Lewis JD, Groven S, Chandrasekaran A, Grandhe S, Diamant C, Singh E, Oliveira G, Wang X, Molparia B, Torkamani A. Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Nov;23(11):2054–2060. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000001221 PMCID: PMC5647120

- Candy S, Borok G, Wright JP, Boniface V, Goodman R. The value of an elimination diet in the management of patients with ulcerative colitis. S Afr Med J. S Afr Med J; 1995 Nov;85(11). PMID: 8597010

- Charlebois A, Rosenfeld G, Bressler B. The Impact of Dietary Interventions on the Symptoms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016 Jun 10;56(8):1370–1378. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2012.760515 PMID: 25569442

- Zhan Y-L, Zhan Y-A, Dai S-X. Is a low FODMAP diet beneficial for patients with inflammatory bowel disease? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2018 Feb;37(1):123–129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.019 PMID: 28587774

- Pedersen N, Ankersen DV, Felding M, Wachmann H, Végh Z, Molzen L, Burisch J, Andersen JR, Munkholm P. Low-FODMAP diet reduces irritable bowel symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 May 14;23(18):3356–3366. http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i18.3356 PMCID: PMC5434443

- Heuschkel RB, Menache CC, Megerian JT, Baird AE. Enteral nutrition and corticosteroids in the treatment of acute Crohn’s disease in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000 Jul;31(1):8–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005176-200007000-00005 PMID: 10896064

- Day AS, Whitten KE, Sidler M, Lemberg DA. Systematic review: nutritional therapy in paediatric Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Feb 15;27(4):293–307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03578.x PMID: 18045244

- Borrelli O, Cordischi L, Cirulli M, Paganelli M, Labalestra V, Uccini S, Russo PM, Cucchiara S. Polymeric diet alone versus corticosteroids in the treatment of active pediatric Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled open-label trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Jun;4(6):744–753. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.010 PMID: 16682258

- Verma S, Brown S, Kirkwood B, Giaffer MH. Polymeric versus elemental diet as primary treatment in active Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Mar;95(3):735–739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01527.x PMID: 10710067

- Berni Canani R, Terrin G, Borrelli O, Romano MT, Manguso F, Coruzzo A, D’Armiento F, Romeo EF, Cucchiara S. Short- and long-term therapeutic efficacy of nutritional therapy and corticosteroids in paediatric Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2006 Jun;38(6):381–387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2005.10.005 PMID: 16301010

- Knight C, El-Matary W, Spray C, Sandhu BK. Long-term outcome of nutritional therapy in paediatric Crohn’s disease. Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;24(5):775–779. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2005.03.005 PMID: 15904998

- Heuschkel R. Enteral nutrition should be used to induce remission in childhood Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis. 2009 Sep 24;27(3):297–305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000228564 PMID: 19786755

- Hiwatashi N. Enteral nutrition for Crohn’s disease in Japan. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997 Oct;40(10 Suppl):S48–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02062020 PMID: 9378012

- Rajendran N, Kumar D. Role of diet in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar 28;16(12):1442–1448. http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1442 PMCID: PMC2846248

- Nakahigashi M, Yamamoto T, Sacco R, Hanai H, Kobayashi F. Enteral nutrition for maintaining remission in patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease: current status and future perspectives. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016 Jan;31(1):1–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2348-x PMID: 26272197

- Osvaldo Borrelli, Letizia Cordischi, Manuela Cirulli, Massimiliano Paganelli, Valeria Labalestra, Stefania Uccini, Paolo M. Russo, Salvatore Cucchiara. Polymeric Diet Alone Versus Corticosteroids in the Treatment of Active Pediatric Crohn’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Open-Label Trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, American Gastroenterological Association. 2006. Volume 4, Issue 6, Pages 744-753. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.010

- Pabón-Carrasco M, Ramirez-Baena L, Vilar-Palomo S, Castro-Méndez A, Martos-García R, Rodríguez-Gallego I. Probiotics as a Coadjuvant Factor in Active or Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease of Adults-A Meta-Analytical Study. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 28;12(9). http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu12092628 PMCID: PMC7551006

- Losurdo G, Iannone A, Contaldo A, Ierardi E, Di Leo A, Principi M. Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in Ulcerative Colitis Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015 Dec;24(4):499–505. http://dx.doi.org/10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.244.ecn PMID: 26697577

- Avalueva EB, Uspenskiĭ IP, Tkachenko EI, Sitkin SI. [Use of Saccharomyces boulardii in treating patients inflammatory bowel diseases (clinical trial)]. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol . 2010;(7):103–111. PMID: 21033091

- Mazidi M, Rezaie P, Ferns GA, Vatanparast H. Impact of Probiotic Administration on Serum C-Reactive Protein Concentrations: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Nutrients. Nutrients; 2017 Jan 3;9(1). PMID: 28054937

- Gerbarg PL, Jacob VE, Stevens L, Bosworth BP, Chabouni F, DeFilippis EM, Warren R, Trivellas M, Patel PV, Webb CD, Harbus MD, Christos PJ, Brown RP, Scherl EJ. The Effect of Breathing, Movement, and Meditation on Psychological and Physical Symptoms and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2886–2896. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000568 PMID: 26426148

- Kuo B, Bhasin M, Jacquart J, Scult MA, Slipp L, Riklin EIK, Lepoutre V, Comosa N, Norton B-A, Dassatti A, Rosenblum J, Thurler AH, Surjanhata BC, Hasheminejad NN, Kagan L, Slawsby E, Rao SR, Macklin EA, Fricchione GL, Benson H, Libermann TA, Korzenik J, Denninger JW. Genomic and clinical effects associated with a relaxation response mind-body intervention in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 30;10(4):e0123861. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123861 PMCID: PMC4415769

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!