Which is Better, Low Fat or Low Carb?

Stanford research provides the answer, with professor Christopher Gardner.

The recent DIETFITS study explored how well people would do on a low-carb vs. a low-fat diet, based on genotype or the way they secrete insulin. The results of the study didn’t reveal a link with genotype pattern or insulin. But they showed roughly equal weight-loss success for participants on both diets. Notably, the study forbid participants in both diets to eat added sugar or refined grain, and encouraged both groups to eat copious vegetables. More than whether your diet is high-fat or low-fat, it seems that high-quality whole foods are a critical factor in healthy weight loss.

Study: Effect of Low-Fat Versus Low-Carb Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association with Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion Also known as DIETFITS trial

- A healthy constructed low carb diet vs low fat diet, again, as long as they’re healthy, seem to be beneficial for the majority of people

- Will everyone do well on these? Not necessarily, it’s worth testing both options to see how your body responds individually

- Gene testing didn’t seem to offer any benefit in this study

- Quality of food matters (on any diet)

Learn More

- Nutrition.stanford.edu

- True Health Initiative – David Katz website

In this episode

Episode Intro … 00:00:40

Inspiration for Low-Carb vs. Low-Fat Study … 00:02:32

Design of DIETFITS Study … 00:05:47

What Is Quality in a Diet? … 00:12:48

What Is Truly Low Carb (or Low Fat)? … 00:19:38

Gene Correlation: a Red Herring? … 00:26:09

Results of Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb Study … 00:29:43

Overlap of the Healthiest Diets … 00:33:16

Satiety: the Natural Weight Control? … 00:36:18

Both Diets Won, But Questions Remain … 00:41:14

Rules for Different Dieters … 00:44:49

Episode Wrap-Up … 00:49:30

Download this Episode (right click link and ‘Save As’)

Episode Intro

Dr. Michael Ruscio, DC: Hi everyone. Welcome to Dr. Ruscio Radio. Today I am here with Christopher Gardner. Man, the more I talk to this guy, the more I just love what he has to say. He’s published another study, looking at this mystical bias-filled issue of carbohydrates, fat, and diet. And I think he’s one of the few guys in the space who doesn’t seem to be highly biased in one direction or another. So Chris, super excited to have you back on the show, welcome.

Prof. Christopher Gardner, PhD: Thanks, glad to be here.

DrMR: You recently published a paper that I’ve mentioned and I’ve quoted a number of times on the podcast, so I’m very grateful for the opportunity to have you expand upon this. The paper appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and it was entitled “Effect of Low-Fat Versus Low-Carb Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association with Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion.” For short, it’s known as the DIETFITS trial. Essentially the study was trying to see if genotyping and insulin predicted whether someone would do better on a high-carb or on a low-carb diet.

One of the things that you found in some of your previous research—just to get the audience up to speed here—is that there may have been this (what I believe you termed) heterogeneity in insulin secretions. Meaning, there were differences in how much carbohydrate people could handle because of the way they secreted insulin. And you thought perhaps the reason why some people do well on a high-carb versus a low-carb diet has to do with their insulin genetics, or individuality, if you will. In this study, you really wanted to assess that. That’s a bit of the context. Before I steal all your thunder here, can you get people up to speed on what you’ve done and what led to the inception of this most recent study?

Inspiration for Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb Study

CG: Yeah, that was pretty good. I’m going to flip it a little bit though. So we did a weight-loss study that we published in 2007, that was Atkins versus Ornish, versus Zone, versus LEARN. There were some small differences. Statistically, the only two that were different were Zone and Atkins, the two low-carb diets. What was fascinating was, I created not just the average and standard deviation graph, but what we call a waterfall plot, which shows every single person in the study, and it showed this massive range. Within all four of those diet groups, somebody lost 50 pounds and somebody gained 10. So there’s a 60-pound range of response to the same advice. And I can’t tell you how many colleagues asked me for that slide. Not the main paper, not the main paper’s main graphic, that one. They were kind of blown away with how, as you said, heterogeneous the results were.

So I went looking for an explanation. And when I went looking, this idea of insulin resistance came up: that two people can have the same amount of excess body fat, but one is metabolically really healthy and one can be metabolically unhealthy. We found three other papers that said, “Wow, if you do that, and you tweak the way you randomize people, it looks like some people do better on low-carb and some people do better on low-fat, and that might be a way to explain it.” Another group had come along, saying that they had this multilocused genotype, with three SNPs (single-nucleotide polymorphisms), that, when taken together and looking at our old data, suggested that they could predict who would do better on one than the other.

So I was really excited, thinking, “Look, I’m going to start a whole new study, only low-carb and low-fat. I’m going to assume, as often it happens, they’re really pretty close at the end of 12 months.” And that’s not even my main hypothesis. I’m not hypothesizing that one is better than the other.

I think we should find out which diet is better for whom, so we should build into this thing enough people that we can see highly successful people, and failures, and everything in the middle, on both diets. And wouldn’t it help the American public if we could find some tricks to see who might be predisposed to do better on one than the other? That would help explain some of this variability.

DrMR: One of the things that I think people would be really eager to see would be, “Gosh, could I do a gene test, and could that tell me if I should be low-carb or low-fat?” Because, of course, the consumer’s confronted with all this debate. Some people will tell you that fat’s gonna kill you. Other people will tell you that carbs are gonna kill you. It’s like, “Ah, where do I go?” Well, maybe this gene test or polymorphism test could help inform that. So it’s definitely an attractive offer that the study was trying to answer. Let’s starting weighting into some of the setup that you put forward. There are a couple questions that I know some of the audience is going to have, regarding the low-carb versus high-carb intake. So let’s start going into the design.

Design of DIETFITS Study

CG: Sure, okay. Well, this was fun because I had to hire health educators. So let’s make this clear. This was the feeding study. There were 609 people in it. There was no way I was going to make food and feed them all for a year. And I wanted this to be more generalizable, so I wanted it to be free-living people, buying food, preparing it, eating it on their own. I thought that would have a longer-lasting, more generalizable impact, but that’s hard. It’s hard to get everybody to be perfect in this. So the way we designed it was 22 evening classes, Michael.

You’d come once a week, for eight weeks. Then every other week, then every third week, then once a month. It added up to 22 evening classes. With 609 people, we had to stretch it out over a few years. The fun for me—here’s the insider scoop that you don’t really get reading the paper—is hiring the staff that would teach this. The requirement in hiring was they had to be willing to teach both. We did it in five cohorts, so roughly 120 per group, over time. And every time we got a new cohort, each health educator had to start a new low-fat and a new low-carb class, and teach them with equal enthusiasm. That was part of the hiring criteria.

DrMR: Was that challenging?

CG: It wasn’t. We got some great people. The staff meetings in the beginning were really fascinating. Some of the dieticians, who were health educators, favored low-fat, and some favored low-carb, and they got together in a room. And after year one and year two, we kept hearing all these stories about their classes. Really, they were just stunned with the range of responses that they saw. Some of their own personal beliefs, and what they thought they knew, were overturned (and some of it was kind of silly). There was a low-fat proponent who said, “Oh, my low-carb class is doing way better than my low-fat, I was wrong,” and then the health educator next to her said, “No, that’s not what happened to me. I was sure low-carb was gonna do better, but my low-fat is doing better.”

As time went on, they saw that there were huge successes in both diet groups. And we kind of knew that part of the answer before we ever got to analyzing the data—and unmasking, and blinding—because these five women had watched the participants over the course of three or four years. They didn’t know what the insulin resistance was, they didn’t know what the genotype was, but they knew that, on average, both diets were the same. Some people thrived, and some people failed.

DrMR: Which is a great exercise and a great example in being open-minded. This is one of the things I’ve continually tried to perpetuate on the podcast: if we look, we can find data to support differing approaches on any one controversial issue. So it’s important not to wrap the patient or the client into that philosophical dichotomy, but rather just try to listen to their body to help them find what’s going to work best for them.

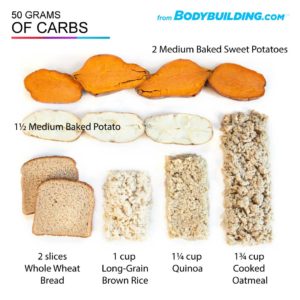

So for the carbohydrate breakdown (and please correct me here if I have any of this wrong) you were looking at 48% carbohydrate in the high-carb group to 30% carbohydrate in the low-carb group. If you do a little math for about 2500 calories—maybe middle of the road, maybe guys are going to be a little less than that, girls are going to be a little more than that—that’s putting it in the ballpark of about 300 grams to about 187 grams. That’s a rough approximation. Is that an accurate representation of the diversion of the carb intake?

CG: Well, wait a sec. We’ve got to talk about two different things. We’ve got to talk about 12-month data, and we’ve got to talk about 3-month data. To lead into that story, what was this approach we took? Let me ask you to back up, just for a minute, and let me ask you to send a three-by-five index card out to all your listeners, and right now have them write down what the definition of low-fat is and what the definition of low-carb is.

Let’s wait… one, two, three. Okay, they’re mailing them all in now. Oh, fascinating. They all came up with different numbers. Some of them used grams, some of them used percents. Wow, there’s no consensus among your listeners about what low-fat and low-carb would be!

Obviously, I’m just making this up, but as we started the study, we thought, “What is it that we want here?” And one of the things we wanted was something challenging, realistic, and generalizable. We came up with this phrase. This is just going to roll off your tongue soon, Michael, I promise. Limbo-Titrate-Quality.

So the limbo phase was the first eight weeks. We asked both groups to get to 20 grams of carb or 20 grams of fat. We don’t have a really official diet assessment at eight weeks, and we never intended to. Some people were type triple As, and they did this in two weeks. And some people struggled, and at eight weeks, they weren’t quite there.

We told them in advance, “We really need you to do this to be part of the study, but we did make up the number. We just made up 20 grams because, to do that, you’re going to have to throw almost everything away in your fridge and your cupboard right now, and start new. And that’s what we want you to think of. Really, we want to psychologically anchor you really low.”

“Oh my God, I am in an NIH-funded Stanford-run study. I’ve got to take this seriously. America’s waiting for me, for the answers. I’m going to really change my diet.”

And we said, “If you get to 20 grams of fat or carb, you’re likely not meeting all your nutrient needs. If you looked at the sum of foods that you had to eat to get that low, you’re probably missing some nutrients, and we’re really not anxious for you to take supplements to make up the deficit. After you get there, try to stay for a little while, and then we want you to titrate back up. Add 5, or 10, or 15 grams back, see what happens.”

“Are you still losing weight? Ah, but you’re still hungry? Ah, you’re finding this impossible in social settings? Well, then this isn’t right. You need to do more than that. So add a little more back.”

“Ah, it’s getting a little easier. Oh, but the weight is coming back on. Okay, in titration, you know what you can do. You can go back down again.”

We ask them to titrate up or down, with the goal being that, at the end, they’d be able to look us in the eye and say, “Look, this is the lowest I can go and conceivably stay at. So if the study’s over and I’m doing well, this is something I can do for the rest of my life.” We explained that was the goal that this, the long-term diet, the 12-month diet, would be something they could live with forever.

What Is Quality in a Diet?

The last piece of Limbo-Titrate-Quality was the quality side. We said, “All right, don’t game the system. Please don’t go buy the low-fat cookies or the low-carb bread. We want you to go to the farmers market, cook for yourself, not eat in the car, not eat in front of a screen, take a bite with a fork and put it down. We really want you to be buying real whole foods, and we really want you to eat sensibly, without gaming the system with some of the packaged, processed crap that would let you meet numbers but not quality.”

We had a couple of things that were identical for both groups, Michael. We said: no added sugar, no refined grain. We said that to low-fat too, even though those are both low-fat. Added sugar has no fat, refined grain has no fat. We said none of those. Eat as many vegetables as you can all day. Now wait… veggies are mostly carbs, but we told the low-carbers to eat as many veggies as they could all day. It’s really not that many calories from veggies, they’re so bulky and so full of water, so we said that. As many veggies as you can, no added sugar or refined grain, and don’t count calories. We want you to feel satiated. More importantly than hitting some target of calories to cut back on, just focus on lowering fat or carbs, with quality, to a point that’s satiating, but don’t count calories.

And we got this really fascinating response from people. They’re like, “Really? It’s a weight-loss study. I’m sure I’m supposed to count calories.” We said, “Not in this study.” They said, “Oh, I’m so relieved. Oh, I’ve tried so many times, and I count the calories, and they don’t add up, and I gain weight anyway.” So it’s really fascinating that we intentionally chose not to prescribe a calorie restriction and to keep the focus on cutting out the foods that are highest in fat or highest in carb, depending on which group you’re in, and focusing on quality.

That’s the approach we took. The numbers you’re seeing in the paper about what carb and fat targets they hit… they never had a target to hit. We just said, “America’s waiting for you to define what realistically low-carb and low-fat are. And, because the whole hypothesis is some of you will do better on one than the other, you’re probably sitting across the table from somebody who’s more or less predisposed than you. They might get lower than you, easier than you. Don’t beat yourself up. They were likely predisposed to have an easier time getting low.” We tried to take away the guilt, or the shame, or the expectation, which I think really helped us get our 80% retention at the end of 12 months.

DrMR: We’ll pepper in some of your conclusions along with this, but one of the things I think was just fantastic about what you did in this study was, it was not a low-quality diet for those who are on the low-fat. Sometimes what you’ll see is—and I’m sure people listening can identify with this—someone who goes on a low-fat diet eats a lot of refined and processed grains. And they’re probably eating a ton of carbs. I think we all know that with refined grains, you can pack on calories. When guys are trying to body build and gain weight, it’s refined carbs they turn to to try to get in all these easy calories.

You had them focus on healthy, higher-carb foods. So there wasn’t this bias in the study where you’re putting all these fruits, vegetables, and healthy fats in the low-carb group, against lots of refined grains in the high-carb group, and falsely proclaiming, “Ah, see, low-carb is a better diet.” I think that was a real strength of the study, which I don’t believe has been done in many of the studies previously. What does some of the background there look like? Do you feel there to be a bit of poor selection of the high-carb diet, at least in some of the research, which falsely vilifies or makes the higher-carb diets look unhealthy?

CG: Yeah, I really do. In one of my favorite examples (I won’t name any names), I was looking at fiber. If you’re on a low-fat diet, you get to eat all kinds of beans, whole grains, fruits, veggies. Those are all full of fiber. In one of the studies I looked at, the low-carb and low-fat group ended up with the exact same amount of fiber at the end of the study. I thought, “Oh, I know how you do that on low-fat. Refined grain and added sugar. It doesn’t have fat and it doesn’t have fiber.” That’s not a fair comparison.

Sponsored Resources

DrMR: Hi, everyone. Let’s talk about bone broth and probiotics, both of which helped to make this podcast possible. Functional Medicine Formulations contains a line of probiotics that I personally developed, and I’m super excited to be able to offer you the same probiotics that I’ve been using in the clinic for years and are a byproduct of an extensive review of the literature plus my own clinical experience.

In this line, you will find my favorite three probiotics in all three of the main categories that work synergistically to help you fight biosis, like SIBO, candida yeast, and H. pylori, help to eradicate parasites, help to reduce leaky gut and repair the gut barrier, and can improve gas, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and may even improve mood, skin, sleep, and thyroid function because of the far-reaching impact of the gut. You can learn more about these at drruscio.com/probiotics.

I’d also like to thank Kettle & Fire, who makes one of my favorite bone broths. Now, you’ve probably heard that bone broth can help via a variety of mechanisms, by helping to repair your gut, by soothing inflammation and repairing joints, by nourishing your hair, skin, and nails and having this almost anti-aging effect, and this is in part because bone broth is very nutrient rich, and especially Kettle & Fire bone broth, which uses non-GMO, organic, and free-range ingredients, and they really do have an excellent product.

Now, if you go to kettleandfire.com/drruscio, they are going to offer our audience 15% off and free shipping on any orders of six cartons or more, so definitely check them out at kettleandfire.com/drruscio.

What Is Truly Low Carb (or Low Fat)?

DrMR: This is one of the major strengths of this study. Looking at the carb content—when you look at the dietary intake per time point—you see that people at baseline were both consuming about 240 grams of carbohydrate per day. And then, the high-carb group actually decreased down to about 200 grams of carbs per day, and maintained about 212 grams from there. They actually saw a relative decrease in their carb intake, likely because they were focusing on healthier forms of carbohydrate.

Comparing that with the low-carb group, they also started off at about 240, 246 specifically, and then they hit 96 grams at three months, and then they leveled out between either 115 or 130. There’s definitely a difference here. Some would criticize that 212 grams in the high-carb group compared to 130 grams in the low-carb group isn’t going low-carb enough. I see both sides of this argument, but I don’t know that getting people down to 70ish grams of carbs per day is what’s going to be best for everyone. I’m certainly open to some people feeling better on that very low-carbohydrate intake, but I also think there are some people who will crash on that and actually end up feeling worse. What is your response to the people who say, “Well, this diet wasn’t low-carb enough, therefore it doesn’t show how beneficial the low-carb arm could’ve been”?

CG: Yeah, so I have two responses to that. The first one is, simply, it was supposed to be generalizable. It was supposed to be maintained for long-term, and so we asked the participants to define what it was. How low is the lowest you can go? Lower than that, something that you can’t sustain…

DrMR: It’s not practical, sure.

CG: Yeah, one of the things that a lot of us agree on is, if you can’t sustain it, then after the diet’s over and you quit, the weight comes back on. That’s why, early on, the health educators stopped calling them diets and started calling them eating plans. They wanted everybody to be on an eating plan that they would continue. My second response to that, Michael, is we’re in the middle of doing a sub-analysis of the ones who most successfully lowered their carbs and their fat. I think the low-fat people should be just as upset. The Ornish, McDougall, Esselstyn folks are gonna say, “Ah, that wasn’t a low-fat diet. That wasn’t low enough,” but they had the same hint. We had 300 people in each group, so we went back and found the 20 who were basically ketogenic and Ornish at three months.

Those were the ones who were the most successful, and then we tracked them out to 12 months… nowhere near. The top less than 10%, at three months, most enthusiastic, best achievers didn’t hold it until 12 months. They added a lot of carb back on low-carb. They added a lot of fat back on low-fat. So, I could imprison them. I could put them in a room and slide food under the door. But, boy, if I can’t even take the top less than 10%, and get them to maintain this with some really enthusiastic, knowledgeable dieticians …

We did ask all the participants, in all groups, to rate the dieticians for enthusiasm and knowledge, on a scale of one to five. Every one of them scored between 4.6 and 4.9 on enthusiasm and knowledge. Those would be my two push-backs.

DrMR: Yeah, I think those are absolutely fair. There’s academics, and then there’s application of those academics, and this is where I think one can sometimes struggle. Something looks good on paper but then, in the clinical setting, it’s very hard to apply that same thing. The caution I’ll make for the doctors and the clinicians listening to this is, be careful that you don’t have such hard-nosed parameters in your practice that the only people who are sticking around are the small subset of highly-compliant people. That definitely can and likely will happen. So you can’t have a doctor who’s a staunch ketogenic advocate and says, “I’ll only work with people who go on a ketogenic diet.”

That person is likely going to help people, no quarrel about that. But they’ll likely have—in my opinion anyway—a bit of a skewed reality. They’ll be saying, “Well, yeah, people don’t seem to have a hard time with compliance, and we’re getting great results.” My burning question there is, how many people come in, see you one time, and then never come back? That’s what I think eludes some people who have built a practice helping people who are in that small subset of highly-motivated people. It’s always been my position that it’s great to be able to serve the people who are highly-motivated, but we don’t want to do that at the expense of people who are not highly-motivated, and not have a broader philosophy we can open into for people who can’t get to 70 grams of carbohydrate in the long-term.

CG: And the flip-side of that: if you’re a real staunch proponent of one, and somebody comes in zealous about the opposite end, be open-minded enough. On all diets, practically, out there, someone succeeds. You’re cutting that person off at the knees if you say, “I’m sorry, I’m such a firm believer in my religious faith for this diet that I won’t see you if you’re on the other diet.”

We can learn so much from them if we say, “Oh, wow.” This is what the dieticians would do. They came and really thought one was better. They saw people thriving on both, including the opposite one that they didn’t think was better, and said it was humbling and, professionally, extremely helpful. They said, “Oh my God, when this study is done, my practice is going to change.”

Gene Correlation: A Red Herring?

DrMR: Awesome, that’s great. Going more into the results now—I’ll put this simply, and then please fill it in—it doesn’t seem that the gene testing or the SNP assessments really helped predict if one group would do better on a given diet than another. And perhaps I had misread that in the study, but it seemed pretty clear, at least from what I read. I think that’s telling for the audience. One of the things I’ve cautioned the audience about is getting pulled into some of these companies that are taking testing and bringing them direct-to-consumer with all these claims, like mapping your diet with this gene assessment. I’m certainly open. But I just keep seeing more information not showing the gene testing to be highly predictive.

CG: Yeah, absolutely.

DrMR: What did you find?

CG: Nothing there for genotype. Picture how this got initiated. We originally had 311 participants in the A to Z study, which is where we went back retroactively and looked for this. We actually only had DNA for 130 people. There were four diets. That’s not many people per diet, by the time we get down to splitting them into four diet groups. There was a statistically significant relationship, but that’s going back retroactively. That’s hypothesis-generating, not hypothesis-testing. Which leads you to suggest, “Well, we should test this going forward.” And we did, and we didn’t replicate it.

Is that crazy? Is that not how science works? That’s exactly how science works. You generate a hypothesis, you test it, and we didn’t replicate it in a larger, better-controlled study.

There was absolutely nothing there. It wasn’t that we just picked those out of a hat. There was a rationale behind it that I don’t have time to go into. But it’s in the methods paper, if you want to get the methods paper. We had pilot data that suggested this would work. It was all very reasonable, but I have to give you an uppity comment that one of our postdocs gave when the results came back in.

He said, “Given that there’s 50 to several hundred SNPs associated with obesity, Professor Gardner, dear mentor, you’re telling me that, of the possible one million permutations of SNPs, we have tested one three-SNP multilocused genotype and found that it didn’t work? So now we only have 999 thousand and 999 more permutations to look at in follow-up studies?”

DrMR: Yup, a lot of work left.

CG: Agh!

DrMR: That’s such a great comment. Because I think, sometimes—especially for a health consumer—it’s easy to overlook the complexity of the human machine and think, “Well, boy, if I can test these three markers, that should give me a good idea.” The genotyping and the microbiota assays… there’s so much complexity there that it’s challenging to get a read. One other question that I did want to ask. Did the SNPs correlate with glucose tolerance? I know you were looking at glucose tolerance also, but I didn’t catch if the SNPs predicted glucose tolerance.

CG: To be honest, after we failed to see anything big going on, we didn’t look.

DrMR: Gotcha, which makes sense. Because what would it really matter, if there was no change in body weight and some of the more practical measures that you were assessing?

CG: Yup. Passed on that one.

Results of Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb Study

DrMR: Okay. Essentially, your conclusion was that there was weight-loss in both groups that was pretty much equivalent.

CG: 6500 pounds, so pretty much 12 pounds on average, after 12 months. But this time we had people losing 60 pounds and gaining 20 in both groups. So it was an 80 pound range of response. If you make this waterfall plot—I don’t know how well that comes across on audio, but I assume it makes sense—everybody’s a bar in the graph. Some go down because you lost weight, some go up because you gained weight, some are around zero because nothing much happened. If you just rank them from the most weight loss to the most weight gain and you turn this into a graphic, the two look superimposable.

You can’t tell the difference when you’ve got hundreds of people above and hundreds of people below on the graph. They look mind-numbingly identical. Which is just awesome that they both lost 12 pounds on average. Technically low-carb lost 13 and low-fat lost 12. Really, would you change your whole diet for a year, for one pound of average difference? Especially because I can find tons of individuals on both diets that did better than tons of individuals on the other one. So it’s still just filled much more with individual variability than a pattern of low-fat versus low-carb.

DrMR: Agreed. What I take away from that finding is, the big picture you want to start with is food quality. That’s the first fight we need to concern ourselves with, instead of trying to coerce someone into low-carb or low-fat. From there, once that’s situated, reassess how someone’s doing. If the endpoint hasn’t been met, consider having them try one diet for a term, and then another diet for a term, to see, experientially, if you can figure out which one their individual chemistry will respond best to.

CG: And I would ask your clinician listeners to go further than that. If somebody says they’re Mediterranean, say, “Wow, I can’t believe that didn’t work for you.” Ask them what they meant by Mediterranean. If they say, “I had an Egg McMuffin for breakfast, a Big Mac for lunch, a Whopper for dinner, but I keep this jigger of olive oil next to my nightstand, and every night before I go to bed, I swill that olive oil. That’s my Mediterranean diet.”

“No! Oh my God, there’s so much more to it than that.” When they say keto, and they’re eating meat all day… “No, keto’s all fat! It’s not all meat.”

When they say, “I’m vegan. Yeah, I had a white flour tortilla, and I had a Coke. Those are both vegan, right?” “Yes! But…”

Come on, you’re going to have to push and get some details. I think you can take almost any of the diets out there and undermine it with the worst possible choices consistent with that pattern. You can even take the one that you feel like you vilify, and see, “Wow, son of gun, the way you described the way you’re doing it is not how I pictured it. I pictured people doing it another way.” I think it’s often closer. If you really pick the highest-quality keto, Med, vegan, vegetarian, whatever, there’s a lot more similarity, I think, than difference.

Overlap of the Healthiest Diets

DrMR: Especially if you’re focusing on food quality. And I’ve heard you say before that you were sitting on a panel, I don’t recall where, but you found it comical that the paleo versus vegan, versus keto, were all arguing amongst probably what is the less important 20%. When the 80% of the impact is what everyone agrees upon, yet we concern ourselves with the small differences.

CG: Yeah, we keep bickering. Yeah, it was the Institute of Functional Medicine. It was Mediterranean, paleo, and vegan. I said, “So, what do you guys think about added sugar?”

“Oh, no.”

“Refined grain?”

“No, we all want to get rid of it.”

“Vegetables?”

“Oh, as many as you can.”

“Okay, so how many Americans, do you think, have a problem with added sugar, refined grain, and vegetables?”

“Oh, they all have a problem with that.”

Could we start there, please? Could we just start there? Can I go into a little satiety rant, for a minute, Michael?

DrMR: Please.

CG: In the middle of our study, some new guidelines came out for obesity in JACC, the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, and it got published some other places. There hadn’t been any good diet obesity guidelines since the 1998 NIH Consensus Conference, and the conclusion of that one was low-fat is really the only way to lose weight.

In 2013, this new recommendation came out and said, “Look, there have been dozens and dozens of studies, so let me tell you all the types of diets that we found some evidence for. Mediterranean, vegetarian, vegan, keto, low fat, gluten free.” They listed them all, basically, and they said, “We’ve found some evidence that some people can lose weight on pretty much any of these diets.” Then they had a couple interesting phrases at the end.

One was, “The most consistent thing was a reduction in calories.” Okay, so let’s not go to the are-all-calories-equal thing for the moment, but all of them that achieved lowering calories lost weight. They said, “But we did find two types.” One was a prescribed energy restriction, and one was an achieved energy restriction. And that knocked me backwards, because I thought, “Wait, in DIETFITS, we never told them that there was any prescribed caloric restriction. They lost 6500 pounds all together, but we never said, ‘Cut back on a certain number of calories.’ We said low-fat or low-carb.”

A lot of weight-loss at six months often comes back on rapidly from six to 12. We actually had a lot of weight-loss at six months that was maintained to 12. I think part of that was not feeling like you were deprived and hungry, and you couldn’t wait until you were finished. We were trying to get them to follow an eating pattern.

Satiety: the Natural Weight Control?

I think the next thing I’d like to focus on is satiety. I think, if you could eat fewer calories and feel satiated, that’s the kind of thing that would help with your weight management. In line with what you were just saying a minute ago, Michael, I want to build on that.

Picture two different individuals. They’ve all done really well at getting rid of added sugar, refined grain, and adding vegetables to their diets. They’re still both struggling with weight. You say, “Okay, for breakfast I want you both to try some steel-cut oats, some skim milk, and some berries. I want it to be this very low-fat breakfast.” And you ask them two hours later how they’re doing. One says, “I’m still really full. Boy, those steel-cut oats are really filling,” and the other one says, “No, I’m kind of hungry already. I think I need more calories.” You have them switch the next day.

Someone has cheesy eggs, and says, “Oh, my God, I can’t actually finish the plate. It’s super satiating to have all that egg and all that cheese. I’m fine.” The other one says, “Wow, this is delicious. Could I have a second helping?” They’re just packing on the calories, because there’s 9 calories per gram in fat, they’re eating a lot of fat, and they’ve got no self-control. And I’m thinking, “What if you got it all right, the foundation, and then you found somebody really is more satiated on low-fat and somebody’s really more satiated on low-carb?” We have room for that. We have good choices along both of those lines, and so I would love to see, for long-term effects, if we really think about a whole food diet that’s variable and addresses satiety.

DrMR: Yeah, it’d be interesting to see if that’s what is driving the differences in responses to a low-carb versus a low-fat diet right now. Maybe that’s why some people are succeeding and failing: because they’re getting paired from a satiation perspective with the right diet or the incorrect diet.

CG: That’s a direction I’d like to move in. I don’t have the answer for that, but I was hypothesizing.

DrMR: That is very interesting. I do hope you publish that study, so we can then learn more from the great work you’ve been doing. Just to piggyback on something you said a moment ago, I’ve found either giving patients a diet book or a dietary handout to be very helpful. I don’t get very deep, in my practice, into macros. It’s more managing issues in the bowel with, say, a low FODMAP diet compared to a paleo diet. And there I have found that diet handouts are very important, or having a health coach or nutritionist that you refer with to give people feedback.

Because you’re right, if you just let people go out on the internet and figure it out, there is so much confusion that that’s really throwing someone to the wolves. Having either materials or staff personnel to refer with, I think, is incredibly helpful, so people don’t take whatever idea they have about diet X and run with it, or go on the internet and get even more confused at what to eat and put in their mouth.

CG: Yeah, I agree. I really think that the professional nutrition community has become more sophisticated. We’ve got certified diabetes educators, and we’ve got all kinds of sport nutritionists. The old model for the dietician was a hospital person who provided low-sodium diets and not a whole lot of excitement. But now—with performance nutrition, the obesity epidemic, being followed by the diabetes epidemic—there are some dieticians who are really loving their jobs, getting really into the metabolism of it all, that are super informed and super excited about it. Absolutely, some of those people are critical for helping patients and clients through these times.

View Dr. Ruscio’s Additional Resources

Both Diets Won, But Questions Remain…

DrMR: Chris, as we come to a close here, I want to recap a couple of the conclusions. Please feel free to add anything to this or modify it. A healthily-constructed low-carb versus a low-fat diet, as long as they’re both healthy, seem to be beneficial for at least the majority of people. How we define the majority is probably up for debate, but that seems to be a great starting point. Will everyone do well on either one of these? Perhaps not, and you need to go through some individualization to get there.

The gene testing, at least the gene testing that you used, didn’t seem to offer any benefit. So perhaps a starting point for people would be to focus on those dietary fundamentals that we talked about, and then consider working with a professional to either engage in a healthy low-carb diet or a healthy low-fat diet. Would you add, modify anything there? And what closing thoughts do you want to leave people with?

CG: No, that was perfect. The second primary outcome was the insulin resistance. I was actually stunned that that didn’t work. We didn’t mention that these are all non-diabetics, but we did have a lot of people with pre-diabetes or metabolic syndrome and we had a lot of people that were hyperinsulinemic. Even that didn’t predict differences.

My conclusion there was where we’ve been going with this whole thing. Once you’ve done a healthful job with either of those diets as a foundation, most people will do better. Still room for further tweaking, absolutely, especially around satiety, as we were just discussing. But as long as they’re both along a healthful line… obviously that’s not easily translated by everyone, but get some help from a professional or do your homework. It really isn’t that hard. Less added sugar, less refined grain, more whole foods, more vegetables, that’s the basis. And then bio-hack your satiety after that. That would be my take on it now.

DrMR: Was this just a fasting blood glucose that you were using to define insulin resistance, or was it another marker?

CG: Oral glucose tolerance test. We had a 75-gram glucose challenge. We took glucose and insulin at baseline, 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 120 minutes. We really got some fabulous data. We did 1500 oral glucose tolerance tests over time. Ah, a lot of work!

DrMR: That’s no easy task. Some of this even pulls the strings of a sacred cow in integrative medicine, which is: those who are prediabetic or diabetic must be low-carb. I certainly like the idea of being more carb-avoidant in someone with these symptoms, but again, there’s also data showing that a higher-carb diet can help with diabetes. Even something that seems so logically plausible comes back to this same philosophy of food quality, just avoiding unhealthy foods in terms of sources of carbohydrates, like processed grain, and added sugars that really seem to stack up. As long as you’re operating from that foundation, you’ll likely get results for even someone who is pre-diabetic, with a “healthy” but higher-carb dietary approach.

Rules for Different Dieters

CG: You mentioned this in the beginning, Michael. If the low-fatters are eating whole grains, beans, and legumes, and fruits, but getting rid of added sugar and refined grains, for most people, that’s a lower-carb diet (just those few categories there). I want to add one note to that. We gave both groups that same advice, to get rid of added sugars and refined grains. But the low-carb group was much better at it. I think, in their head, they said, “All right, I really don’t get any carbs at all. If I’m going to cheat at all, if I’m going to get anything, it’s definitely going to be a piece of fruit. I get to have vegetables, but I really miss a piece of fruit.”

I think the low-fatters thought, “Well, I’ve been pretty good. I got rid of a lot of added sugar and refined grain, but after all, I am low-fat. And I really want that dark chocolate tonight, with the sugar in it, so yup, I’m going to have the sugar.” The low-carbers, if you look at the data in the table, they did much better at getting rid of refined grain and added sugar, even though they both had that same advice.

Part of that just could be a messaging advantage for a clinician. A vegan or somebody who’s favoring low-fat, thinking, “God, I just cannot get this patient to get rid of that. Okay, I’m gonna have them go low-carb,” and then, boy, if you have anything at all other than veggies, it’s fruit. And you see they might do an even better job of getting rid of those really simple sugars that are giving them trouble.

DrMR: I really do not like telling people, “Hit this many calories,” and specific macro breakdowns, I just find it to be very confining, especially when we’re trying to deal with other issues, like, “Are you FODMAP-sensitive? Are you dairy-sensitive? Do you have a bacterial overgrowth that we’re trying to treat?” There’s enough other things going on, where this doesn’t seem relevant to my practice, to be that particular.

But one of the things I do occasionally recommend is either upping their carb intake, if someone’s too low-carb. Or more relevant to our conversation and this point would be, giving them a carb ceiling and saying, “Make sure you don’t eat any more than… ” Oftentimes, I’ll say 125 grams of carbs per day, if I think someone’s in a carbohydrate excess.

They’re doing some tracking, but they don’t have to say, “Well, I can only have this much fat. I need to have that much protein,” and they feel like they’re just trying to balance this chemistry set, and it’s very difficult. Rather, they can eat other healthy foods, but they have to keep their total daily carbohydrate intake below a certain ceiling. What are your thoughts about that?

CG: I think, for some people, that’s going to work. I think, for different people, different simple rules work for them. It could be the intermediate fasting, “I’m not going to eat between 10:00 and 6:00 PM.” I get that. “I’m not going to eat after 8:00 PM.” I get that. But what you just said reminded me a little of the old Weight Watchers strategy, where you were counting points. You could have chocolate cake, but once you had it, you used up a lot of your points. They don’t do that anymore.

I think they were finding that, with the ceiling of points, some people were using the points to have the chocolate cake and nothing else. And then they weren’t getting all their nutrients. I think your upper limit of 125 grams would work for a bunch of people. I think there are going to be others that are going to game it and say, “Look, I get 125 grams. Let’s see, a 64-ounce Big Gulp, that has… oh, a little over. Okay, I’ll have a 32-ounce soda.”

DrMR: Right, so it comes back to the foundation of food quality. That has to be where we start from, because hopefully, that would prevent any Big Gulp drinking or at least greatly mitigate it.

CG: But some people will get it. Yeah, you’ve just to feel out, for your patients and clients, what they get. I’m not a clinician, I’m a researcher. I’m quite sure it’s complicated to ask your patients about food. It takes a lot longer than you often have time for, as a clinician, getting accurate stuff out of them. I don’t know if diet apps are helping. Sharing that with your clinician and physician takes a long time too. I’m in awe of some of the things you and your colleagues do.

DrMR: Well, it’s many people, I think, trying to just figure out what works and share the information. Hopefully, as we all work together here and share, we bring a better message to the public, and help really to diminish the amount of confusion that people are dealing with.

Episode Wrap-Up

That’s something that I think is an unfortunate byproduct of the wealth of information that we have on the internet. You can get access to almost anything. But the challenge is, you can get access to almost anything. If you’re trying to do one diet, you can go and find a bunch of people saying that diet’s going to kill you. And then you can find a bunch of people saying that that’s the only diet that’ll help keep you alive. Hopefully, as we all communicate with one another, we can simplify that landscape for people at least a little bit.

CG: Yeah, and I’ll give a plug to something David Katz started, called the True Health Initiative. He’s got about 300 different nutrition professionals, across 30 or 40 countries. The fundamental part of that is, you open the webpages and it’s a bunch of faces of professionals and big words across it: “We agree.” The whole point is, we don’t agree on everything.

We all have our favorites. But we agree on more things that we disagree on, so stop playing us off against each other. If you listen, we mostly agree, and there’s room for some healthy disagreement. Most of us agree that people are screwing up on some of the basics, like the added sugar, refined grain, not enough veggies, and not enough whole foods.

DrMR: Great, love it. Anything else that you want to leave people with?

CG: No, but thanks for being on the team here. We need a whole lot of help clearing up what seems like is more confusing than it really is. So I look forward to following your work, and I look forward to doing some more studies we can talk about.

DrMR: Yeah. Well, absolutely. Is there a certain website that you keep up for people, or are you mainly just publishing the papers and people would need to read the academic paper?

CG: I’m a social media troglodyte. You can find stuff at nutrition.stanford.edu. It’s not very fancy, but it has a lot of our work, and some of the stuff on the side, and it has some videos, but it’s not very sophisticated. That’s the only one I would recommend.

DrMR: Awesome. Well, Chris, thank you again. I deeply, deeply appreciate your work. What you’re doing has been a huge breath of fresh air, so thank you a thousand-fold.

CG: Very kind. Pleasure to be here, Michael. Thanks.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.➕ Resources & Links

- Effect of Low-Fat Versus Low-Carb Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association with Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion

- True Health Initiative

- nutrition.stanford.edu

- Kettle & Fire

- Functional Medicine Formulations Probiotics

- Dr. Ruscio Resources

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!