How To Care for an Overactive Thyroid and Graves’ Disease

Conventional treatments for hyperthyroidism — which is much more common for women than for men— can come with significant side effects or permanent damage to your thyroid gland. The good news is that there are a lot of other options. Natural remedies for hyperthyroidism and general thyroid function improvement include:

- Dietary changes, such as a gluten-free diet

- Specific supplements, such as selenium, probiotics, and vitamin D

- Herbs, such as bugleweed and lemon balm

Let’s explore what hyperthyroidism is, the risks of conventional treatment, and the many natural remedies for hyperthyroidism.

What Is Hyperthyroidism?

Your thyroid gland is located at the front of your neck, and it produces thyroid hormones. These hormones regulate many essential endocrine functions in your body, including energy production, digestive function, and more.

Hyperthyroidism — also called an overactive thyroid — is when your thyroid gland produces too much thyroid hormone. The most common reason for hyperthyroidism is an autoimmune attack on the thyroid gland called Graves’ disease. Though it’s far less common than other thyroid disorders, an estimated one in 200 Americans has Graves’ disease 1. The majority of thyroid patients, including hyperthyroid patients, are women 2 3.

Symptoms of Hyperthyroidism and Graves’ Disease

Symptoms of excess thyroid hormone include 4:

- Increased heart rate or heart palpitations

- Unexplained weight loss

- Anxiety

- Increased bowel movements or diarrhea

- Menstrual changes

- Muscle weakness or tremors

- Enlargement of your thyroid gland (goiter)

- Increased sweating, or clammy skin

- Erectile dysfunction or decreased libido

- Graves’ ophthalmopathy (eye complications such as eye-bulging, tearing, dryness, irritation, puffy eyelids, inflammation, light sensitivity, blurred vision, or pain)

- Thick, red skin usually on the shins or tops of the feet (Graves’ dermopathy)

Your doctor usually diagnoses hyperthyroidism with:

- A blood test for levels of thyroid hormones

- Or, a radioactive iodine uptake test

If your blood test shows low TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) and high free T4 thyroid hormone, this means you are hyperthyroid 5. If you also have elevated thyroid antibodies, including thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI), thyroid peroxidase (TPO), or thyroglobulin (TG) antibodies, you may be diagnosed with Graves’ disease 6 7.

The radioactive iodine test can help rule out other possibilities, such as thyroid nodules, toxic multinodular goiter, or thyroid cancer 8. This test does have some potential side effects, so be sure to discuss it with your doctor before taking it.

Causes of Hyperthyroid Disease

There are three main causes of hyperthyroidism:

- Graves’ disease, an autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland that leads to hyperthyroidism. Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism.

- Thyroiditis, or swelling of the thyroid. Thyroiditis can be caused by viral infections 9, radiation 10, certain medications 11, or recent childbirth (postpartum thyroiditis) 12.

- Thyroid nodules may affect the production of thyroid hormone and induce hyperthyroidism 13.

No matter the cause, it’s very important to get hyperthyroidism under control. As excessive thyroid activity can lead to heart damage and a life-threatening “thyroid storm,” we want to utilize effective treatment approaches that not only decrease the effects of excessive thyroid hormone, but, if possible, address the root causes for hyperthyroidism in the first place 14.

Natural Treatment Options for Hyperthyroidism and Thyroid Wellness

Treatment of hyperthyroidism must accomplish two goals:

- Stop the damaging effects of excess thyroid hormone

- Resolve the root causes so that the symptoms stop and don’t recur

Conventional treatment for hyperthyroidism tries to address both of these but doesn’t address the frequently underlying autoimmunity. Anti-thyroid medications — such as methimazole or drugs like beta-blockers that reduce the potential heart damage of excess thyroid hormone — are the first level of treatment for hyperthyroidism. While these medications can help reduce symptoms of hyperthyroidism, they do not significantly address the underlying cause(s) for excess thyroid hormone.

Secondary conventional treatments, such as radioactive iodine therapy or thyroid surgery, permanently damage or remove the thyroid gland to permanently stop the production of thyroid hormones. This stops hyperthyroid symptoms and the excess circulating thyroid hormones. However, destruction of the thyroid gland leaves patients hypothyroid and needing T4 (thyroxine) replacement therapy for life and still doesn’t address the underlying autoimmunity.

The good news is there are natural remedies for hyperthyroidism that rival conventional treatments in their effectiveness and also have fewer risks, consequences, and side effects. They are also likely to address the underlying autoimmunity and other root causes of hyperthyroidism. Let’s discuss.

Diet for Hyperthyroidism and the Gut-Thyroid Connection

Research suggests your gut health strongly influences your thyroid and your risk for autoimmunity 15. One of the biggest steps you can take to improve your gut and immune health is to eat a healthy diet.

Intestinal permeability 16 — also called leaky gut — is suspected to contribute to the development of autoimmune disease 17 18 19 20 21 22 23. We know that imbalanced gut bacteria can increase intestinal permeability 24 25 26, as can eating certain foods, such as gluten 27.

Most research on thyroid health and diet has studied how different foods impact an underactive thyroid (also known as hypothyroidism). However, some of these studies may be relevant for autoimmune hyperthyroidism, because they show an anti-inflammatory diet can reduce thyroid antibodies.

For example, a gluten-free diet was shown in one study to reduce thyroid antibodies in a group of women with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis 28. A gene associated with Graves’ disease (CTLA-4) 29 is also associated with celiac disease 30 31, indicating that gluten sensitivity may be a factor for some Graves’ patients.

A simple, anti-inflammatory, whole-food diet that is gluten-free, nutrient-dense, and high in healthy antioxidants, like the paleo diet, is a great place to start improving your gut and thyroid health and to improve autoimmunity. The paleo diet has been shown to reduce inflammation by reducing exposure to foods that may trigger an immune response 32 33.

My patient Amy saw significant improvement in her hyperthyroid symptoms from adopting a gluten-free diet.

Natural Remedies for Hyperthyroidism: Supplements

Supplements have a lot of promise as natural remedies for hyperthyroidism and play one of a few different roles. These include:

- Reducing thyroid antibodies

- Blocking the action of excess thyroid hormones

- Reducing levels of thyroid hormones

- Reducing hyperthyroid symptoms

- Preventing relapse

Let’s review what we know about supplements for hyperthyroidism.

Selenium

Selenium, a mineral that is used as a dietary supplement, has a number of specific, documented benefits for Graves’ disease.

Patients with Graves’ disease are more likely to have lower selenium levels 34, and a meta-analysis showed that patients with high antibody levels are more likely to have a relapse 35. Selenium has been shown to reduce antibodies and the symptoms associated with Graves’ disease 36, and higher selenium blood levels have been shown to reduce the relapse rate of Graves’ 37.

Selenium reduces the eye complications associated with Graves’ 38 39 40, plus those that are associated with radioactive iodine treatment 41 42.

Finally, two studies indicated that selenium supplementation improved treatment outcomes for patients using conventional hyperthyroid treatments, such as methimazole and radioactive iodine treatment 43 44 45.

Overall, this is very good evidence that selenium supplementation is worth a trial in your hyperthyroidism treatment plan.

L-Carnitine

L-Carnitine is an amino acid supplement that has been shown to reduce or prevent hyperthyroid symptoms. It’s fast-acting, has a very low risk of side effects, and is even safe for pregnant women with Graves’ disease 46. A clinical trial found that L-carnitine had a positive effect on 47:

- Weakness and fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Palpitations

- Nervousness

- Insomnia

- Tremors

- Heart rate

- Bone mineral density

However, in this study, L-carnitine did not affect the levels of TSH, free T4, or free T3 thyroid hormone.

L-carnitine can also be used to treat a “thyroid storm”, the most severe, life-threatening form of hyperthyroidism 48 49.

Lemon Balm & Bugleweed

Two herbs, lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) and bugleweed (Lycopus europaeus), have been shown in limited studies to reduce hyperthyroid symptoms and to block or reduce thyroid hormones.

In one study, bugleweed was shown to be as effective as beta-blockers for protecting the heart from damage from hyperthyroidism 50. In another study, it was shown to reduce an elevated heart rate from Graves’ disease in humans and rats 51 52.

Additional studies have indicated that bugleweed and lemon balm may block or decrease thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and reduce T3 and T4 hormone levels, which would reduce the symptoms of hyperthyroidism 53.

The evidence here is more preliminary and lower quality than with selenium or L-carnitine, but bugleweed and lemon balm are certainly worth considering as a short-term trial if you are hyperthyroid. Hopefully, future research will confirm these effects in larger samples.

Short-Term Iodine

The iodine molecule is the backbone of thyroid hormones, but curiously, research suggests that excess iodine may trigger hypothyroidism 54 55, which makes iodine potentially useful for treating hyperthyroidism. A small study showed that 150 mg per day of potassium iodide reversed hyperthyroidism in some patients 56. However, the study noted that the effect wasn’t permanent. Therefore, iodine may help you get your symptom under control while you use other natural remedies for hyperthyroidism.

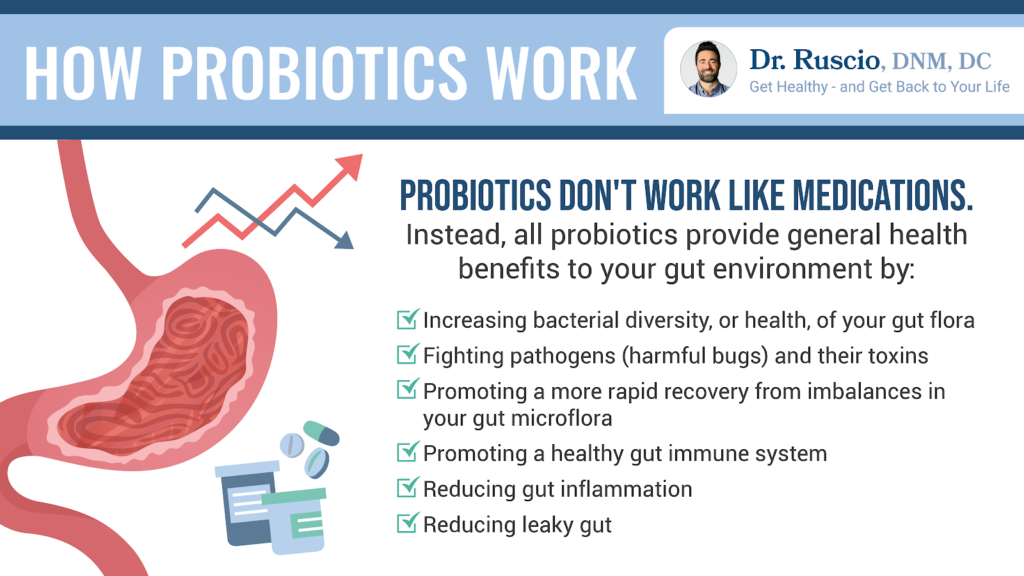

Probiotics

It might not seem like probiotics would have much to do with thyroid disease, but a growing body of research shows that thyroid patients very often have gut imbalances. People with thyroid disease more often have SIBO 57 58, leaky gut 59, low stomach acid 60 61 62, and celiac disease 63, as well as gut infections like H. pylori 64 or parasites 65. One particular study noted a strong association between H. pylori infection and Graves’ disease 66.

Probiotics help rebalance the gut microbiome and the immune system, reduce gut inflammation, repair the gut lining, and may improve hyperthyroid symptoms, including anxiety 67. Even better, probiotics have a very low incidence of negative side effects compared to conventional treatment.

Between their safety profile and their demonstrated effects on thyroid health, a trial of triple probiotic therapy is worth exploring.

Vitamin D

Most thyroid-related vitamin D research has studied hypothyroid patients. This research suggests that vitamin D deficiency may be associated with higher levels of thyroid antibodies 68 and that supplementation with vitamin D may decrease them 69. But one study showed that hyperthyroid patients who had lower vitamin D levels were more likely to relapse 70.

Considered together, these data suggest vitamin D supplementation may help reduce thyroid antibodies and relapse after treatment for hyperthyroidism.

Stress Reduction

Stress reduction is good supportive care, no matter what your health condition is. This is especially true for hyperthyroidism, where common symptoms include an increased heart rate, palpitations, and anxiety. There is no direct evidence that stress reduction practices can improve Graves’ disease or hyperthyroidism, but practices such as meditation, yoga, or cognitive behavioral therapy may support your healing process while you work on other treatments.

The Bottom Line

You don’t need to destroy your thyroid gland to get control of your hyperthyroidism. Simple diet changes, supplements, and stress reduction, sometimes alongside medication, can bring your body back into balance. If you need support managing your thyroid problems, consider becoming a patient at the Ruscio Institute for Functional Health.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.

➕ References

- https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/graves-disease#common

- Łacka K, Fraczek MM. Podział i etiopatogeneza nadczynności tarczycy [Classification and etiology of hyperthyroidism]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2014 Mar;36(213):206-11. Polish. PMID: 24779222.

- Vanderpump MP. The epidemiology of thyroid disease. Br Med Bull. 2011;99:39-51. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr030. PMID: 21893493.

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/graves-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20356240

- Reid J, Wheeler S. Hyperthyroidism: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Aug 15;72(4):623-630.

- Bohuslavizki KH, vom Baur E, Weger B, Krebs C, Saller B, Wetlitzky O, Musiol N, Kühnel W, Lambrecht HG, Clausen M. Evaluation of chemiluminescence immunoassays for detecting thyroglobulin (Tg) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO) autoantibodies using the IMMULITE 2000 system. Clin Lab. 2000;46(1-2):23-31. PMID: 10745978.

- Thushani Siriwardhane, Karthik Krishna, Vinodh Ranganathan, Vasanth Jayaraman, Tianhao Wang, Kang Bei, Sarah Ashman, Karenah Rajasekaran, John J. Rajasekaran, Hari Krishnamurthy, “Significance of Anti-TPO as an Early Predictive Marker in Thyroid Disease”, Autoimmune Diseases, vol. 2019, Article ID 1684074, 6 pages, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1684074

- Taylor RB. The 10-minute diagnosis manual: symptoms and signs in the time-limited encounter. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

- Sweeney L, Stewart C, Gaitonde D. Thyroiditis: An Integrated Approach. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Sep 15;90(6):389-396.

- Nagayama Y. Radiation-related thyroid autoimmunity and dysfunction. J Radiat Res. 2018 Apr 1;59(suppl_2):ii98-ii107. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrx054. PMID: 29069397; PMCID: PMC5941148.

- De Leo S, Lee SY, Braverman LE. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet. 2016 Aug 27;388(10047):906-918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00278-6. Epub 2016 Mar 30. PMID: 27038492; PMCID: PMC5014602.

- Keely EJ. Postpartum thyroiditis: an autoimmune thyroid disorder which predicts future thyroid health. Obstet Med. 2011 Mar;4(1):7-11. doi: 10.1258/om.2010.100041. Epub 2011 Mar 1. PMID: 27579088; PMCID: PMC4989649.

- De Leo S, Lee SY, Braverman LE. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet. 2016 Aug 27;388(10047):906-918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00278-6. Epub 2016 Mar 30. PMID: 27038492; PMCID: PMC5014602.

- Osuna PM, Udovcic M, Sharma MD. Hyperthyroidism and the Heart. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2017 Apr-Jun;13(2):60-63. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-13-2-60. PMID: 28740583; PMCID: PMC5512680.

- Knezevic J, Starchl C, Tmava Berisha A, Amrein K. Thyroid-Gut-Axis: How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function? Nutrients. 2020 Jun 12;12(6):1769. doi: 10.3390/nu12061769. PMID: 32545596; PMCID: PMC7353203.

- Mu Q, Kirby J, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2017 May 23;8:598. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598. PMID: 28588585; PMCID: PMC5440529.

- Tripathi A, Lammers KM, Goldblum S, Shea-Donohue T, Netzel-Arnett S, Buzza MS, Antalis TM, Vogel SN, Zhao A, Yang S, Arrietta MC, Meddings JB, Fasano A. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16799–804.

- Morris G, Berk M, Carvalho AF, Caso JR, Sanz Y, Maes M. The Role of Microbiota and Intestinal Permeability in the Pathophysiology of Autoimmune and Neuroimmune Processes with an Emphasis on Inflammatory Bowel Disease Type 1 Diabetes and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(40):6058-6075. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160914182822. PMID: 27634186.

- Bjarnason I, Williams P, So A, Zanelli GD, Levi AJ, Gumpel JM, Peters TJ, Ansell B. Intestinal permeability and inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis: effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1984 Nov 24;2(8413):1171-4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92739-9. PMID: 6150232.

- Goebel A, Buhner S, Schedel R, Lochs H, Sprotte G. Altered intestinal permeability in patients with primary fibromyalgia and in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 Aug;47(8):1223-7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken140. Epub 2008 Jun 7. PMID: 18540025.

- Sturgeon C, Fasano A. Zonulin, a regulator of epithelial and endothelial barrier functions, and its involvement in chronic inflammatory diseases. Tissue Barriers. 2016 Oct 21;4(4):e1251384. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2016.1251384. PMID: 28123927; PMCID: PMC5214347.

- Küçükemre Aydın B, Yıldız M, Akgün A, Topal N, Adal E, Önal H. Children with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Have Increased Intestinal Permeability: Results of a Pilot Study. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2020 Sep 2;12(3):303-307. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2020.2019.0186. Epub 2020 Jan 28. PMID: 31990165; PMCID: PMC7499128.

- Drago S, El Asmar R, Di Pierro M, Grazia Clemente M, Tripathi A, Sapone A, Thakar M, Iacono G, Carroccio A, D’Agate C, Not T, Zampini L, Catassi C, Fasano A. Gliadin, zonulin and gut permeability: Effects on celiac and non-celiac intestinal mucosa and intestinal cell lines. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006 Apr;41(4):408-19. doi: 10.1080/00365520500235334. PMID: 16635908.

- Canakis A, Haroon M, Weber HC. Irritable bowel syndrome and gut microbiota. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2020 Feb;27(1):28-35. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000523. PMID: 31789724.

- Tripathi A, Lammers KM, Goldblum S, Shea-Donohue T, Netzel-Arnett S, Buzza MS, Antalis TM, Vogel SN, Zhao A, Yang S, Arrietta MC, Meddings JB, Fasano A. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16799–804.

- Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, Ockhuizen T, Schulzke JD, Serino M, Tilg H, Watson A, Wells JM. Intestinal permeability–a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov 18;14:189. doi: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7. PMID: 25407511; PMCID: PMC4253991.

- Fasano A. Intestinal permeability and its regulation by zonulin: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Oct;10(10):1096-100. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.012. Epub 2012 Aug 16. PMID: 22902773; PMCID: PMC3458511.

- Krysiak R, Szkróbka W, Okopień B. The Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Thyroid Autoimmunity in Drug-Naïve Women with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: A Pilot Study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019 Jul;127(7):417-422. doi: 10.1055/a-0653-7108. Epub 2018 Jul 30. PMID: 30060266.

- Pastuszak-Lewandoska D, Sewerynek E, Domańska D, Gładyś A, Skrzypczak R, Brzeziańska E. CTLA-4 gene polymorphisms and their influence on predisposition to autoimmune thyroid diseases (Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis). Arch Med Sci. 2012 Jul 4;8(3):415-21. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.28593. PMID: 22851994; PMCID: PMC3400896.

- Song GG, Kim JH, Kim YH, Lee YH. Association between CTLA-4 polymorphisms and susceptibility to Celiac disease: a meta-analysis. Hum Immunol. 2013 Sep;74(9):1214-8. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.05.014. Epub 2013 Jun 12. PMID: 23770251.

- Ch’ng CL, Jones MK, Kingham JG. Celiac disease and autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin Med Res. 2007 Oct;5(3):184-92. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.738. PMID: 18056028; PMCID: PMC2111403.

- Whalen KA, McCullough ML, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Judd S, Bostick RM. Paleolithic and Mediterranean Diet Pattern Scores Are Inversely Associated with Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Balance in Adults. J Nutr. 2016 Jun;146(6):1217-26. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.224048. Epub 2016 Apr 20. PMID: 27099230; PMCID: PMC4877627.

- Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutr J. 2014 Jan 16;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-5. PMID: 24428901; PMCID: PMC3896778.

- Bülow Pedersen I, Knudsen N, Carlé A, Schomburg L, Köhrle J, Jørgensen T, Rasmussen LB, Ovesen L, Laurberg P. Serum selenium is low in newly diagnosed Graves’ disease: a population-based study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013 Oct;79(4):584-90. doi: 10.1111/cen.12185. Epub 2013 Mar 27. PMID: 23448365.

- Feldt-Rasmussen U, Schleusener H, Carayon P. Meta-analysis evaluation of the impact of thyrotropin receptor antibodies on long term remission after medical therapy of Graves’ disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994 Jan;78(1):98-102. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.1.8288723. PMID: 8288723.

- Duntas LH. The evolving role of selenium in the treatment of graves’ disease and ophthalmopathy. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:736161. doi: 10.1155/2012/736161. Epub 2012 Jan 19. PMID: 22315699; PMCID: PMC3270443.

- Wertenbruch T, Willenberg HS, Sagert C, Nguyen TB, Bahlo M, Feldkamp J, Groeger C, Hermsen D, Scherbaum WA, Schott M. Serum selenium levels in patients with remission and relapse of graves’ disease. Med Chem. 2007 May;3(3):281-4. doi: 10.2174/157340607780620662. PMID: 17504200.

- Drutel A, Archambeaud F, Caron P. Selenium and the thyroid gland: more good news for clinicians. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013 Feb;78(2):155-64. doi: 10.1111/cen.12066. PMID: 23046013.

- Duntas LH. The evolving role of selenium in the treatment of graves’ disease and ophthalmopathy. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:736161. doi: 10.1155/2012/736161. Epub 2012 Jan 19. PMID: 22315699; PMCID: PMC3270443.

- Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, Bartalena L, Prummel M, Stahl M, Altea MA, Nardi M, Pitz S, Boboridis K, Sivelli P, von Arx G, Mourits MP, Baldeschi L, Bencivelli W, Wiersinga W; European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy. Selenium and the course of mild Graves’ orbitopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011 May 19;364(20):1920-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012985. PMID: 21591944.

- Duntas LH. The evolving role of selenium in the treatment of graves’ disease and ophthalmopathy. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:736161. doi: 10.1155/2012/736161. Epub 2012 Jan 19. PMID: 22315699; PMCID: PMC3270443.

- Bacic-Vrca V, Skreb F, Cepelak I, Mayer L, Kusic Z, Petres B. The effect of antioxidant supplementation on superoxide dismutase activity, Cu and Zn levels, and total antioxidant status in erythrocytes of patients with Graves’ disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43(4):383-8. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.069. PMID: 15899653.

- Duntas LH. The evolving role of selenium in the treatment of graves’ disease and ophthalmopathy. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:736161. doi: 10.1155/2012/736161. Epub 2012 Jan 19. PMID: 22315699; PMCID: PMC3270443.

- Bacic-Vrca V, Skreb F, Cepelak I, Mayer L, Kusic Z, Petres B. The effect of antioxidant supplementation on superoxide dismutase activity, Cu and Zn levels, and total antioxidant status in erythrocytes of patients with Graves’ disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43(4):383-8. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.069. PMID: 15899653.

- Xu B, Wu D, Ying H, Zhang Y. A pilot study on the beneficial effects of additional selenium supplementation to methimazole for treating patients with Graves’ disease. Turk J Med Sci. 2019 Jun 18;49(3):715-722. doi: 10.3906/sag-1808-67. PMID: 31023005; PMCID: PMC7018306.

- Benvenga S, Ruggeri RM, Russo A, Lapa D, Campenni A, Trimarchi F. Usefulness of L-carnitine, a naturally occurring peripheral antagonist of thyroid hormone action, in iatrogenic hyperthyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Aug;86(8):3579-94. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7747. PMID: 11502782.

- Benvenga S, Ruggeri RM, Russo A, Lapa D, Campenni A, Trimarchi F. Usefulness of L-carnitine, a naturally occurring peripheral antagonist of thyroid hormone action, in iatrogenic hyperthyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Aug;86(8):3579-94. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7747. PMID: 11502782.

- Benvenga S, Ruggeri RM, Russo A, Lapa D, Campenni A, Trimarchi F. Usefulness of L-carnitine, a naturally occurring peripheral antagonist of thyroid hormone action, in iatrogenic hyperthyroidism: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Aug;86(8):3579-94. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7747. PMID: 11502782.

- Benvenga S, Amato A, Calvani M, Trimarchi F. Effects of carnitine on thyroid hormone action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Nov;1033:158-67. doi: 10.1196/annals.1320.015. PMID: 15591013.

- Vonhoff C, Baumgartner A, Hegger M, Korte B, Biller A, Winterhoff H. Extract of Lycopus europaeus L. reduces cardiac signs of hyperthyroidism in rats. Life Sci. 2006 Feb 2;78(10):1063-70. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.06.014. Epub 2005 Sep 16. PMID: 16150466.

- Beer AM, Wiebelitz KR, Schmidt-Gayk H. Lycopus europaeus (Gypsywort): effects on the thyroidal parameters and symptoms associated with thyroid function. Phytomedicine. 2008 Jan;15(1-2):16-22. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.11.001. PMID: 18083505.

- Vonhoff C, Baumgartner A, Hegger M, Korte B, Biller A, Winterhoff H. Extract of Lycopus europaeus L. reduces cardiac signs of hyperthyroidism in rats. Life Sci. 2006 Feb 2;78(10):1063-70. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.06.014. Epub 2005 Sep 16. PMID: 16150466.

- Auf’mkolk M, Ingbar JC, Kubota K, Amir SM, Ingbar SH. Extracts and auto-oxidized constituents of certain plants inhibit the receptor-binding and the biological activity of Graves’ immunoglobulins. Endocrinology. 1985 May;116(5):1687-93. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-5-1687. PMID: 2985357.

- Foley TP Jr. The relationship between autoimmune thyroid disease and iodine intake: a review. Endokrynol Pol. 1992;43 Suppl 1:53-69. PMID: 1345585.

- Katagiri R, Yuan X, Kobayashi S, Sasaki S. Effect of excess iodine intake on thyroid diseases in different populations: A systematic review and meta-analyses including observational studies. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 10;12(3):e0173722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173722. PMID: 28282437; PMCID: PMC5345857.

- Philippou G, Koutras DA, Piperingos G, Souvatzoglou A, Moulopoulos SD. The effect of iodide on serum thyroid hormone levels in normal persons, in hyperthyroid patients, and in hypothyroid patients on thyroxine replacement. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992 Jun;36(6):573-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02267.x. PMID: 1424182.

- Konrad P, Chojnacki J, Kaczka A, Pawłowicz M, Rudnicki C, Chojnacki C. Ocena czynności tarczycy u osób z zespołem przerostu bakteryjnego jelita cienkiego [Thyroid dysfunction in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2018 Jan 23;44(259):15-18. Polish. PMID: 29374417.

- Brechmann T, Sperlbaum A, Schmiegel W. Levothyroxine therapy and impaired clearance are the strongest contributors to small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Results of a retrospective cohort study. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Feb 7;23(5):842-852. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i5.842. PMID: 28223728; PMCID: PMC5296200.

- Küçükemre Aydın B, Yıldız M, Akgün A, Topal N, Adal E, Önal H. Children with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Have Increased Intestinal Permeability: Results of a Pilot Study. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2020 Sep 2;12(3):303-307. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2020.2019.0186. Epub 2020 Jan 28. PMID: 31990165; PMCID: PMC7499128.

- Cellini M, Santaguida MG, Virili C, Capriello S, Brusca N, Gargano L, Centanni M. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis and Autoimmune Gastritis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017 Apr 26;8:92. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00092. PMID: 28491051; PMCID: PMC5405068.

- Centanni M, Gargano L, Canettieri G, Viceconti N, Franchi A, Delle Fave G, Annibale B. Thyroxine in goiter, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic gastritis. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 27;354(17):1787-95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043903. PMID: 16641395.

- Bugdaci MS, Zuhur SS, Sokmen M, Toksoy B, Bayraktar B, Altuntas Y. The role of Helicobacter pylori in patients with hypothyroidism in whom could not be achieved normal thyrotropin levels despite treatment with high doses of thyroxine. Helicobacter. 2011 Apr;16(2):124-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00830.x. Erratum in: Helicobacter. 2011 Dec;16(6):482. Albayrak, Banu [corrected to Bayraktar, Banu]. PMID: 21435090.

- Knezevic J, Starchl C, Tmava Berisha A, Amrein K. Thyroid-Gut-Axis: How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function? Nutrients. 2020 Jun 12;12(6):1769. doi: 10.3390/nu12061769. PMID: 32545596; PMCID: PMC7353203.

- Choi YM, Kim TY, Kim EY, Jang EK, Jeon MJ, Kim WG, Shong YK, Kim WB. Association between thyroid autoimmunity and Helicobacter pylori infection. Korean J Intern Med. 2017 Mar;32(2):309-313. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2014.369. Epub 2017 Jan 16. PMID: 28092700; PMCID: PMC5339455.

- Rajič B, Arapović J, Raguž K, Bošković M, Babić SM, Maslać S. Eradication of Blastocystis hominis prevents the development of symptomatic Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015 Jul 30;9(7):788-91. doi: 10.3855/jidc.4851. PMID: 26230132.

- Shi WJ, Liu W, Zhou XY, Ye F, Zhang GX. Associations of Helicobacter pylori infection and cytotoxin-associated gene A status with autoimmune thyroid diseases: a meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2013 Oct;23(10):1294-300. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0630. Epub 2013 Sep 11. PMID: 23544831.

-

Yang B, Wei J, Ju P, et al

Effects of regulating intestinal microbiota on anxiety symptoms: A systematic review

- Bozkurt NC, Karbek B, Ucan B, Sahin M, Cakal E, Ozbek M, Delibasi T. The association between severity of vitamin D deficiency and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Endocr Pract. 2013 May-Jun;19(3):479-84. doi: 10.4158/EP12376.OR. PMID: 23337162.

- Wang S, Wu Y, Zuo Z, Zhao Y, Wang K. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on thyroid autoantibody levels in the treatment of autoimmune thyroiditis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Endocrine. 2018 Mar;59(3):499-505. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1532-5. Epub 2018 Jan 31. PMID: 29388046.

- Yasuda T, Okamoto Y, Hamada N, Miyashita K, Takahara M, Sakamoto F, Miyatsuka T, Kitamura T, Katakami N, Kawamori D, Otsuki M, Matsuoka TA, Kaneto H, Shimomura I. Serum vitamin D levels are decreased in patients without remission of Graves’ disease. Endocrine. 2013 Feb;43(1):230-2. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9789-6. Epub 2012 Sep 15. PMID: 22983830; PMCID: PMC3536951.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!