Are Gut Biome Tests Really Worth It?

The Inside Track on Microbiome Tests, and the Evidence Behind Them

- What Is a Gut Biome Test?|

- Microbiome Mapping|

- Detecting Dysbiosis|

- Pathogen/Parasite Testing|

- Other Gut Tests|

- Gut Biome Testing in Context|

- What Creates a Healthy Microbiome?|

- Final Verdict|

Gut biome tests are becoming increasingly popular in the world of functional medicine.

That’s hardly surprising given how important a healthy gut microbiome is to so many aspects of our physical and mental health.

But beyond shedding some light on the type and quantities of microbes in our gut, how useful are these tests at informing how we support our gut health?

In this article we’ll discuss some different types of gut microbiome tests and look at their usefulness and limitations.

Before going into more detail, let’s start with a quick overview.

- Gut biome tests split into those that map the whole microbiome, those that test for dysbiosis (bacteria imbalances in the bowel), and those that test for parasites and pathogens.

- Many of these tests, particularly microbiome mapping tests, tell you about the bacterial community in your gut, but not what this means or what to do about it.

- Microbiome mapping helps scientists and researchers to better understand the gut microbiome, but these tests aren’t useful in a clinical setting yet.

- The same goes for dysbiosis tests — what may be a dysbiotic microbiota for one person may not be for another.

- The diagnosis and treatment of bacterial imbalance/gut dysbiosis is best based on symptoms and addressed with the foundations of good nutrition, probiotic supplements, exercise, and stress management.

- Some stool tests (not specifically gut microbiome tests) do have a role to play in diagnosing gut problems. For example, fecal calprotectin is a reliable marker for inflammatory bowel disease.

- Gut tests that look for specific parasites and pathogens can also be useful, provided they are used and interpreted properly.

What Is a Gut Biome Test?

A gut biome (or microbiome) test involves the patient supplying a stool sample that’s analyzed for its microorganism content, including types of bacteria, as well as sometimes viruses and parasites.

Depending on the stool test kit you’re using, you may need to collect a poop sample in a clean container held over the toilet bowl. Alternatively, the sample collection may involve using only a swab, placed inside a sealed testing tube.

Most gut biome tests use genetic sequencing technologies to identify the composition of your microbiome and to offer insights into your gut and overall health.

These sequencing techniques can include [1]:

- PCR (polymerase chain reaction) analysis: Usually used to detect DNA (genetic material) from known gut pathogens, such as harmful bacteria and viruses.

- Amplicon: Used by academic organizations, including the Human Microbiome Project and the Earth Microbiome Project (of which the American Gut Project is a part). The analysis amplifies specific pieces of gut bacteria DNA for easier identification.

- 16S rRNA sequencing: Used to identify the genuses of bacteria and their abundance relative to each other. Not useful for clinical analysis because each genus can have many species and strains.

- Shotgun metagenomics: Sequences fragments of all DNA, including human, microbial, fungal, and viral, and attempts to give an approximated view of the microbiome [2].

- Metatranscriptomics metaproteomics: Both read gene expression (i.e., which bacterial genes are active) but the results are difficult to interpret. The Gut Intelligence Test developed by Viome uses metatranscriptomics.

- Metabolomics: Assesses the microbiome’s composition based on the metabolites (by products), such as butyrate that the bacteria produce.

Another way of examining the stool is by using culture techniques. In this case, the sample is smeared onto a nutrient-rich gel in a petri dish. This provides nutrients and a controlled environment for any bacteria in the sample to grow, and be identified.

Stool analysis may also look for chemical or biological markers — for example, inflammatory markers — in an attempt to diagnose or distinguish between conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Beware of Overselling

While some gut biome or stool tests have value, I’ve seen them oversold and misused in functional and integrative medicine.

Practitioners may use them with the best of intentions, but may not understand how to interpret the results correctly, or might pin more significance to the results than is warranted. This is generally due to misleading marketing and/or lab reports from the testing companies themselves.

Tests marketed at the general public giving insights into your gut bacteria often cost hundreds of dollars, so manufacturers work hard to convince you that they’re worth buying.

The three main categories of gut biome/tool tests are microbiome mapping, dysbiosis tests, and parasite/pathogen tests.

Microbiome Mapping

This type of gut biome test entails analyzing the genetic profile of your gut’s microbiota composition from a stool sample. It essentially maps out the entirety of your gut microflora and then uses algorithms that compare the DNA of your microbial composition relative to databases of other people’s microbiomes.

This type of test is useful for research and data gathering purposes, but microbiome mapping is not yet at a point where it can offer much information that’s clinically actionable for the individual.

- One 2021 systematic review and meta analysis processed the data from 10 human gut microbiome studies and a total of 1,733 human stool samples. The authors of the review concluded that the web of human host-microbiota-metabolite relationships in the human gut is so complex that much more research is needed in order to decipher and characterize it [3].

- A 2018 literature review explained that while microbiome testing is increasingly available commercially, the state of knowledge relating to microbiome diagnostics is not yet advanced enough to provide much clinical value to doctors or their patients [2].

- Another literature review concluded that there’s no such thing as an ideal microbiota [4].

Some studies have suggested that gut biome mapping tests may be useful for predicting:

- Your glycemic response and how much your blood triglyceride levels rise in response to food [5, 6]

- How your body will age [7]

- Whether you’re at risk of high blood pressure [8]

However, these studies have usually been done by interested parties (i.e, researchers employed by the companies that market the microbiome tests).

Microbiome mapping carried out responsibly as part of advancing scientific knowledge is to be applauded. It will likely result in data that will be useful clinically in the future.

But for now it’s important to exercise caution, as at best, having your gut microbiome mapped won’t really inform what strategies you should take (such as what diet to eat or supplements to take). The results can also lead to unnecessary anxiety or fear, and distract both patients and practitioners from the bigger picture when it comes to gut health and overall wellness.

At worst, microbiome mapping can be a complete rip-off. One sorry example is the now-defunct company called uBiome, which began in 2012 to offer microbiome tests to consumers. In 2019, the FBI raided uBiome for defrauding investors, health insurers, doctors, and clients [9]. Furthermore, the company’s datasets may have been tainted with stool samples from human infants and pets [10].

Detecting Dysbiosis

Some gut biome tests are specifically targeted at identifying gut dysbiosis, defined as an imbalance of beneficial bacteria and bad bacteria in the gut.

However, exactly what defines dysbiosis is still being worked out, so this limits the usefulness of these tests and how their results can be applied. A 2020 review concluded that “dysbiosis” is a broadly used term that’s vaguely defined and often misused [11].

One dysbiosis test, called the GA-map™ Dysbiosis test, which was developed in Norway, may have some validity and is approved and available for practitioner use in the United States.

GA-map was validated by the manufacturers, who claim their test found dysbiosis in 73% of IBS patients, 70% of IBD patients for whom treatment failed, 80% of IBD patients in remission, and 16% of healthy people [12].

That said, other evidence questions this test’s ability to detect IBS [13].

Another dysbiosis test, called the GI360 test (or more specifically, the PCR-DNA element of this test), may also correctly identify a pattern of dysbiosis in IBS and IBD patients, according to research [12]. But it’s important to remember that our knowledge of the clinical implications of specific bacteria in the gut microbiome is truly in its infancy [14].

Overall, while testing may be able to detect dysbiosis, it does not mean the dysbiosis has a causal relationship with disease [15].

Another way of putting this is that a dysbiosis index may be useful as a marker but not a predictor of disease. Given the variations in gut microbiota between healthy people, there’s no clear definition of a “normal” gut microbiota. The idea that the balance of trillions of gut organisms can “tip over” into a clearly pathogenic pattern is also unproven and highly debated [15].

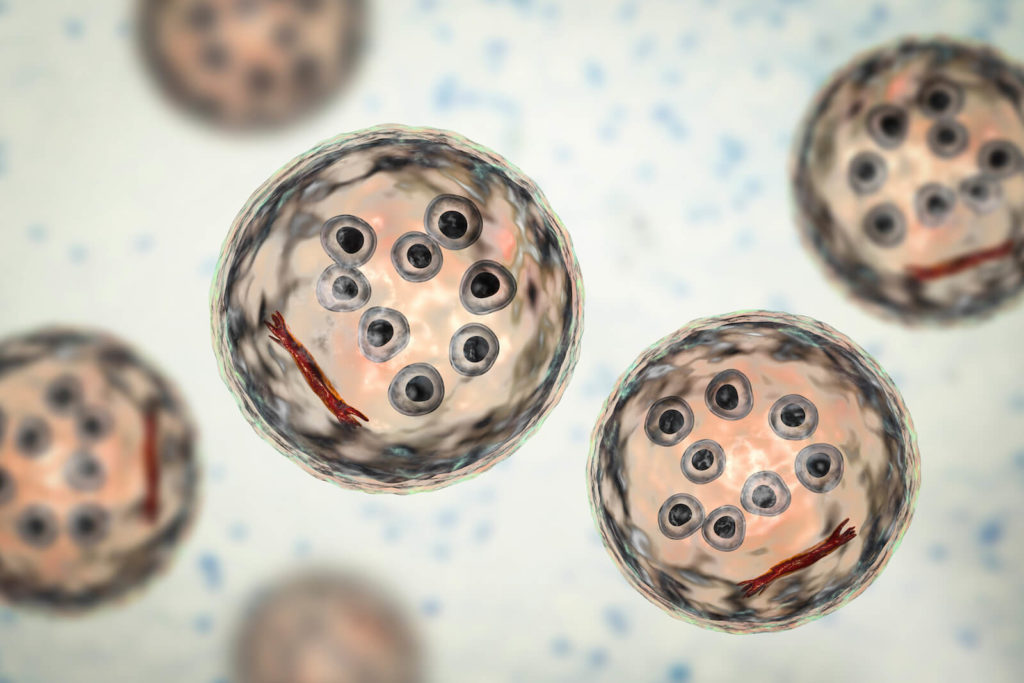

Pathogen/Parasite Testing

Gut biome tests that more specifically analyze parasites/pathogens can be helpful when it comes to detecting overtly harmful organisms in your gut.

However, it’s very important that tests for parasites are used only when they will yield useful information, and in conjunction with a doctor who knows how to interpret the results.

Effective tests for these purposes are stool tests that use culture or PCR to identify known pathogens [1]. Gut biome tests that are mapping tests are NOT recommended for identifying known pathogens, because they collect too broad an array of genetic data.

Parasite-identifying tests can be a problem in overzealous hands, as they can flag protozoan organisms like Endolimax nana and Blastocystis hominis as problematic pathogens, when they may not actually be causing harm.

The tests take a lot of practitioner skill and experience to interpret. If misinterpreted, you could end up with unnecessary treatments to deal with a “pathogen” that’s actually a normal harmless digestive tract resident for you.

Pathogen/parasite tests that have verified benefits if correctly interpreted include BioFire, Verigene, and BD MAX:

- The sensitivity of the BD MAX test was shown in a study to be between 85% and 100% [16]. The BioFire, Verigene, and BD MAX tests’ specificity were shown in another study to be between 98.6% and 100% [17]. This means the tests correctly identified who had a gut infection and who didn’t most of the time.

Other Gut Tests

It’s also worth mentioning a few stool tests that aren’t strictly gut biome tests, but which may be useful in diagnosing gut health issues. The table below provides an at-a-glance guide to these and their potential usefulness (or not). The conclusions are drawn from research and our own clinical experience at the Ruscio Institute for Functional Medicine.

| Gut Test | Condition Diagnosed | Effectiveness |

| Zonulin testing | Leaky gut | Unlikely to be helpful. Zonulin as a marker for a leaky gut is not generally clinically helpful; taking measures to improve gut health is a better approach [18, 19]. A zonulin antibody test may be more informative than a zonulin (blood) serum test [20]. |

| Hydrogen breath testing | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) | Can sometimes be helpful. Sometimes clinically useful for detecting SIBO, especially if a glucose-based breath test is used (less likely to produce a false positive than a lactulose-based one) [21] |

| Vinculin/CdtB antibody testing | IBS-D (diarrhea predominant) | Can sometimes be helpful. Can be useful to determine if diarrhea is due to IBS, or whether more testing is needed to look for celiac disease or IBD. |

| Fecal elastase-1 and fecal steatocrit | Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) | Very likely to be helpful. Both are indicators of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) or bile acid malabsorption (BAM) when positive in patients with diarrhea [22, 23]. |

| Fecal calprotectin | IBD | Very likely to be helpful. A highly accurate indicator of inflammation in the large intestine. When elevated in someone with digestive symptoms, calprotectin can suggest inflammatory bowel disease [24]. |

Gut Biome Testing in Context

Unless there’s clear evidence of an overt infection with a parasitic organism, there’s no set protocol for dealing with the results of a gut biome test.

This is why gut microbiome testing should only be carried out very sparingly. For example, in most cases, knowing where you score on some arbitrary scale of dysbiosis doesn’t change the fact that you’ll need to treat your gut symptoms and the issues that underlie them to feel better.

Working with your gut and how you feel is the crucial thing here, rather than just trying to manipulate your dysbiosis index back to some sort of “normal.”

Dysbiosis Is a Symptom, Not the Cause

Ultimately, while dysbiosis has been linked to various diseases and health conditions, it’s not likely to be causing those conditions. What’s more likely is that dysbiosis is occurring secondary to factors like poor dietary patterns or lifestyle, obesity, immune system reactions, use of certain medications, etc.

As a result, for a healthy gut microbiome, you should focus on supporting your microbial environment (not measuring it and worrying about test results). This involves improving diet and reducing inflammation, along with other foundational steps such as managing stress levels, exercising, and getting quality sleep.

A gardening analogy is very apt here — that is to say if you want healthy microbes to grow in the ecosystem of your gut, you’ve got to tend to the environment of the soil. Treating your gut microbiota with the health inputs of diet and healthy lifestyle is equivalent to supplying the water, sun, and nutrients that’ll make the plants in your garden grow.

What Creates a Healthy Microbiota?

When looking to boost the health of your gut microbiome it pays to stick to the areas where research has something useful to say, which are diet, probiotic supplementation, and if necessary, some further pathogen-removing steps.

Gut-Friendly Diets

At the beginning of your gut-healing journey, trying either the Mediterranean diet or the Paleo diet is a good idea as they can both:

- Control inflammation [25, 26, 27]

- Balance blood sugar [28, 29, 30]

- Provide the right balance of carbohydrates to fuel you, and prebiotic fiber to feed your good bacteria

If these diets don’t resolve symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, and soreness after two to three weeks, the low FODMAP diet may be better. This diet removes problematic prebiotics (fermentable carbs), and is especially useful for symptoms of IBS [31].

Probiotics

High-quality research points to probiotics as the cornerstone of effective gut treatment [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37]. A blend of probiotics can work to encourage healthy populations of intestinal bacteria and inhibit the growth of inflammation-causing microbes.

To take it a step further, my clinical experience has been that the combined use of three categories of probiotic supplements — Lacto-Bifido bacteria, friendly yeasts, and soil microorganisms — can balance gut microbiota and improve gut health more effectively than using one type of probiotics alone [38, 39, 40].

Further Therapies (Bad Bug Removal)

If your symptoms aren’t properly resolved after covering your bases of diet and probiotics, antimicrobial therapy and/or an elemental diet are further approaches to consider. These can both help to correct gut bacteria imbalance and remove lingering bad bacteria.

- Antimicrobials such as Rifaximin (an antibiotic) are well documented to help clear bad bacteria overgrowth [41, 42]. Plant-based antimicrobials [43] such as oregano oil (active ingredient carvacrol) [44], berberine [45], and caprylic acid [46] are natural alternatives.

- An elemental diet provides optimal nutrition in a predigested form. This form of liquid nutrition allows the digestive system to rest and repair, and can be used for a block of a few days or just to replace one or two meals on a regular basis, and is another approach to dealing with overgrowth of bad bacteria. Research has shown that elemental diets deal effectively with SIBO [41, 42] and can significantly improve gut symptoms and flares, even if used only half the time [47].

The Final Verdict on Gut Biome Tests

Microbiome test kits that map out your microbiome are of limited usefulness, even though they’re very popular and seem, on the surface, to supply a lot of interesting information. Private testing companies use marketing techniques to make their tests seem helpful, but research doesn’t back this up.

Tests that check for pathogens in the gut have some useful applications if used and interpreted by an experienced practitioner. Similarly, tests that purport to show whether your gut is dysbiotic can be helpful but may not necessarily change the healing approach, which should include changes to diet and lifestyle.

Some people need extra attention to heal gut issues. We’re here to offer help at the Ruscio Institute for Functional Medicine should you need it — please feel free to contact us.

The Ruscio Institute has developed a range of high-quality formulations to help our patients and audience. If you’re interested in learning more about these products, please click here. Note that there are many other options available, and we encourage you to research which products may be right for you.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, Naturopathic Practitioner, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.➕ References

- Allaband C, McDonald D, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Minich JJ, Tripathi A, Brenner DA, et al. Microbiome 101: studying, analyzing, and interpreting gut microbiome data for clinicians. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):218–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.09.017. PMID: 30240894. PMCID: PMC6391518.

- Staley C, Kaiser T, Khoruts A. Clinician guide to microbiome testing. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Dec;63(12):3167–77. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-018-5299-6. PMID: 30267172.

- Muller E, Algavi YM, Borenstein E. A meta-analysis study of the robustness and universality of gut microbiome-metabolome associations. Microbiome. 2021 Oct 12;9(1):203. DOI: 10.1186/s40168-021-01149-z. PMID: 34641974. PMCID: PMC8507343.

- Guilliams TG. Dysbiosis or adaptation: how stable is the gut microbiome? Altern Ther Health Med. 2016 Oct;22(S3):10–2. PMID: 27866181.

- Tily H, Perlina A, Patridge E, Gline S, Genkin M, Gopu V, et al. Gut microbiome activity contributes to individual variation in glycemic response in adults. BioRxiv. 2019 May 19; DOI: 10.1101/641019.

- Berry SE, Valdes AM, Drew DA, Asnicar F, Mazidi M, Wolf J, et al. Human postprandial responses to food and potential for precision nutrition. Nat Med. 2020 Jun 11;26(6):964–73. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-020-0934-0. PMID: 32528151. PMCID: PMC8265154.

- Gopu V, Cai Y, Krishnan S, Rajagopal S, Camacho FR, Toma R, et al. An accurate aging clock developed from the largest dataset of microbial and human gene expression reveals molecular mechanisms of aging. BioRxiv. 2020 Sep 19; DOI: 10.1101/2020.09.17.301887.

- Louca P, Nogal A, Wells PM, Asnicar F, Wolf J, Steves CJ, et al. Gut microbiome diversity and composition is associated with hypertension in women. J Hypertens. 2021 Sep 1;39(9):1810–6. DOI: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002878. PMID: 33973959. PMCID: PMC7611529.

- Health Test Company UBiome Has Filed For Bankruptcy [Internet]. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexknapp/2019/09/04/health-test-company-ubiome-has-filed-for-bankruptcy/?sh=315885723639

- Poop From Pets and Infants Created Flaws in Research at Startup UBiome [Internet]. Available from: https://www.businessinsider.com/ubiome-poop-testing-startup-problems-science-microbiome-2019-8

- Walter J, Armet AM, Finlay BB, Shanahan F. Establishing or Exaggerating Causality for the Gut Microbiome: Lessons from Human Microbiota-Associated Rodents. Cell. 2020 Jan 23;180(2):221–32. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.025. PMID: 31978342.

- Casén C, Vebø HC, Sekelja M, Hegge FT, Karlsson MK, Ciemniejewska E, et al. Deviations in human gut microbiota: a novel diagnostic test for determining dysbiosis in patients with IBS or IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Jul;42(1):71–83. DOI: 10.1111/apt.13236. PMID: 25973666. PMCID: PMC5029765.

- Aasbrenn M, Valeur J, Farup PG. Evaluation of a faecal dysbiosis test for irritable bowel syndrome in subjects with and without obesity. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2018;78(1–2):109–13. DOI: 10.1080/00365513.2017.1419372. PMID: 29271246.

- Weiss GA, Hennet T. Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017 Aug;74(16):2959–77. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-017-2509-x. PMID: 28352996.

- Wei S, Bahl MI, Baunwall SMD, Hvas CL, Licht TR. Determining gut microbial dysbiosis: a review of applied indexes for assessment of intestinal microbiota imbalances. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021 May 11;87(11). DOI: 10.1128/AEM.00395-21. PMID: 33741632. PMCID: PMC8208139.

- Anderson NW, Buchan BW, Ledeboer NA. Comparison of the BD MAX enteric bacterial panel to routine culture methods for detection of Campylobacter, enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (O157), Salmonella, and Shigella isolates in preserved stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2014 Apr;52(4):1222–4. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.03099-13. PMID: 24430460. PMCID: PMC3993502.

- Huang RSP, Johnson CL, Pritchard L, Hepler R, Ton TT, Dunn JJ. Performance of the Verigene® enteric pathogens test, Biofire FilmArrayTM gastrointestinal panel and Luminex xTAG® gastrointestinal pathogen panel for detection of common enteric pathogens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016 Dec;86(4):336–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.09.013. PMID: 27720206.

- Ohlsson B, Orho-Melander M, Nilsson PM. Higher Levels of Serum Zonulin May Rather Be Associated with Increased Risk of Obesity and Hyperlipidemia, Than with Gastrointestinal Symptoms or Disease Manifestations. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Mar 8;18(3). DOI: 10.3390/ijms18030582. PMID: 28282855. PMCID: PMC5372598.

- Power N, Turpin W, Espin-Garcia O, Smith MI, CCC GEM Project Research Consortium, Croitoru K. Serum zonulin measured by commercial kit fails to correlate with physiologic measures of altered gut permeability in first degree relatives of crohn’s disease patients. Front Physiol. 2021 Mar 25;12:645303. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2021.645303. PMID: 33841181. PMCID: PMC8027468.

- Vojdani A, Vojdani E, Kharrazian D. Fluctuation of zonulin levels in blood vs stability of antibodies. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Aug 21;23(31):5669–79. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i31.5669. PMID: 28883692. PMCID: PMC5569281.

- Rana SV, Sharma S, Kaur J, Sinha SK, Singh K. Comparison of lactulose and glucose breath test for diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2012 Mar 30;85(3):243–7. DOI: 10.1159/000336174. PMID: 22472730.

- Domínguez-Muñoz JE, D Hardt P, Lerch MM, Löhr MJ. Potential for Screening for Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency Using the Fecal Elastase-1 Test. Dig Dis Sci. 2017 May;62(5):1119–30. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-017-4524-z. PMID: 28315028.

- Sugai E, Srur G, Vazquez H, Benito F, Mauriño E, Boerr LA, et al. Steatocrit: a reliable semiquantitative method for detection of steatorrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994 Oct;19(3):206–9. DOI: 10.1097/00004836-199410000-00007. PMID: 7806830.

- Ayling RM, Kok K. Fecal Calprotectin. Adv Clin Chem. 2018 Oct 1;87:161–90. DOI: 10.1016/bs.acc.2018.07.005. PMID: 30342711.

- Whalen KA, McCullough ML, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Judd S, Bostick RM. Paleolithic and Mediterranean Diet Pattern Scores Are Inversely Associated with Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Balance in Adults. J Nutr. 2016 Jun;146(6):1217–26. DOI: 10.3945/jn.115.224048. PMID: 27099230. PMCID: PMC4877627.

- Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutr J. 2014 Jan 16;13:5. DOI: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-5. PMID: 24428901. PMCID: PMC3896778.

- Tsigalou C, Konstantinidis T, Paraschaki A, Stavropoulou E, Voidarou C, Bezirtzoglou E. Mediterranean diet as a tool to combat inflammation and chronic diseases. an overview. Biomedicines. 2020 Jul 8;8(7). DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines8070201. PMID: 32650619. PMCID: PMC7400632.

- Masharani U, Sherchan P, Schloetter M, Stratford S, Xiao A, Sebastian A, et al. Metabolic and physiologic effects from consuming a hunter-gatherer (Paleolithic)-type diet in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015 Aug;69(8):944–8. DOI: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.39. PMID: 25828624.

- Jönsson T, Granfeldt Y, Ahrén B, Branell U-C, Pålsson G, Hansson A, et al. Beneficial effects of a Paleolithic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a randomized cross-over pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009 Jul 16;8:35. DOI: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-35. PMID: 19604407. PMCID: PMC2724493.

- Martín-Peláez S, Fito M, Castaner O. Mediterranean diet effects on type 2 diabetes prevention, disease progression, and related mechanisms. A review. Nutrients. 2020 Jul 27;12(8). DOI: 10.3390/nu12082236. PMID: 32726990. PMCID: PMC7468821.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014 Jan;146(1):67-75.e5. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046. PMID: 24076059.

- Guglielmetti S, Mora D, Gschwender M, Popp K. Randomised clinical trial: Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life–a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 May;33(10):1123–32. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04633.x. PMID: 21418261.

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug;109 Suppl 1:S2-26; quiz S27. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2014.187. PMID: 25091148.

- du Teil Espina M, Gabarrini G, Harmsen HJM, Westra J, van Winkelhoff AJ, van Dijl JM. Talk to your gut: the oral-gut microbiome axis and its immunomodulatory role in the etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2019 Jan 1;43(1):1–18. DOI: 10.1093/femsre/fuy035. PMID: 30219863.

- Li Q, Ren Y, Fu X. Inter-kingdom signaling between gut microbiota and their host. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019 Jun;76(12):2383–9. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-019-03076-7. PMID: 30911771.

- Virili C, Fallahi P, Antonelli A, Benvenga S, Centanni M. Gut microbiota and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018 Dec;19(4):293–300. DOI: 10.1007/s11154-018-9467-y. PMID: 30294759.

- Shamasbi SG, Ghanbari-Homayi S, Mirghafourvand M. The effect of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on hormonal and inflammatory indices in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2020 Mar;59(2):433–50. DOI: 10.1007/s00394-019-02033-1. PMID: 31256251.

- American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, et al. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104 Suppl 1:S1-35. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. PMID: 19521341.

- Ford AC, Quigley EMM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct;109(10):1547–61; quiz 1546, 1562. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2014.202. PMID: 25070051.

- Zhang C, Jiang J, Tian F, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhai Q, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of the effects of probiotics on functional constipation in adults. Clin Nutr. 2020 Oct;39(10):2960–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.01.005. PMID: 32005532.

- Scarpellini E, Giorgio V, Gabrielli M, Filoni S, Vitale G, Tortora A, et al. Rifaximin treatment for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in children with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013 May;17(10):1314–20. PMID: 23740443.

- Shah SC, Day LW, Somsouk M, Sewell JL. Meta-analysis: antibiotic therapy for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Oct;38(8):925–34. DOI: 10.1111/apt.12479. PMID: 24004101. PMCID: PMC3819138.

- Chedid V, Dhalla S, Clarke JO, Roland BC, Dunbar KB, Koh J, et al. Herbal therapy is equivalent to rifaximin for the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014 May;3(3):16–24. DOI: 10.7453/gahmj.2014.019. PMID: 24891990. PMCID: PMC4030608.

- Sharifi-Rad M, Varoni EM, Iriti M, Martorell M, Setzer WN, Del Mar Contreras M, et al. Carvacrol and human health: A comprehensive review. Phytother Res. 2018 Sep;32(9):1675–87. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.6103. PMID: 29744941.

- Yu H-H, Kim K-J, Cha J-D, Kim H-K, Lee Y-E, Choi N-Y, et al. Antimicrobial activity of berberine alone and in combination with ampicillin or oxacillin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Food. 2005;8(4):454–61. DOI: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.454. PMID: 16379555.

- Omura Y, O’Young B, Jones M, Pallos A, Duvvi H, Shimotsuura Y. Caprylic acid in the effective treatment of intractable medical problems of frequent urination, incontinence, chronic upper respiratory infection, root canalled tooth infection, ALS, etc., caused by asbestos & mixed infections of Candida albicans, Helicobacter pylori & cytomegalovirus with or without other microorganisms & mercury. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2011;36(1–2):19–64. PMID: 21830350.

- Takagi S, Utsunomiya K, Kuriyama S, Yokoyama H, Takahashi S, Iwabuchi M, et al. Effectiveness of an “half elemental diet” as maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease: A randomized-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Nov 1;24(9):1333–40. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03120.x. PMID: 17059514.

➕ Links & Resources

Further Reading:

- How to Get Rid of Bad Bacteria in the Gut

- Should You Use a Stool Test to Check Your Gut Health?

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!