Practitioner Research Review – September 2019

Dr. Michael Ruscio’s Monthly – Future of Functional Medicine Review Clinical Newsletter

Practical Solutions for Practitioners

In Today’s Issue

![]()

Research

*Please note: the case study and research studies are not meant to be mutually reinforcing. There is often concept overlap, however the research studies are a collection of the most clinically meaningful research that has been published recently.

Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: A prospective cohort study and meta-analysis

Lancet Public Health. 2018 Sep;3(9):e419-e428. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30135-X.

Study Purpose

- Assess the relationship between carbohydrate intake and mortality.

Intervention

- Studied 15,428 adults aged 45–64 years, in four US communities

- Who completed a dietary questionnaire at enrolment in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study (between 1987 and 1989),

- Who did not report extreme caloric intake (<600 kcal or >4200 kcal per day for men and <500 kcal or >3600 kcal per day for women).

- The primary outcome was all-cause mortality.

- We investigated the association between the percentage of energy from carbohydrate intake and all-cause mortality,

- We assessed whether the substitution of animal or plant sources of fat and protein for carbohydrate affected mortality.

Main Results

- After multivariable adjustment, there was a U-shaped association between the percentage of energy consumed from carbohydrate (mean 48.9%, SD 9·4) and mortality: a percentage of 50–55% energy from carbohydrate was associated with the lowest risk of mortality.

- In the meta-analysis of all cohorts (432,179 participants), both low carbohydrate consumption (<40%) and high carbohydrate consumption (>70%) conferred greater mortality risk than did moderate intake, which was consistent with a U-shaped association (pooled hazard ratio 1·20, 95% CI 1.09–1.32 for low carbohydrate consumption; 1.23, 1.11–1.36 for high carbohydrate consumption).

- However, results varied by the source of macronutrients: mortality increased when carbohydrates were exchanged for animal-derived fat or protein (1.18, 1.08–1.29) and mortality decreased when the substitutions were plant-based (0.82, 0.78–0.87)

- Dr. R’s note: a big question here is was the quality of animal products assessed. Especially when considering this analysis was performed in the low-fat diet craze era, it is important to establish

- whether or not there was a healthy user bias wherein those who were trying to improve their health (exercising, eating higher quality foods) were the ones who were substituting animal protein with plant protein. And, those who were not taking steps to improve their health were eating more animal protein.

- Also, what was the quality of animal products? All animal protein is not the same. Fried chicken compared to baked chicken. Processed sausage compared to free-range beef….

- So, the question is were variables like this control for in a regression analysis; smoking, drinking, exercising, education level, food quality… Let’s read on to find out (hint, the answer is no on food quality, very important).

Limitations

- The authors admit controlling for food quality has been an issue to date

- Furthermore, many previous studies of carbohydrate intake have not accounted for the potential effects of food source

- The authors find that a low carb diet, which is animal and fat-based, was associated with increased mortality. This effect was not observed when the diet was low carb and a plant-based emphasis.

- When assessing total carbohydrate without regard to specific food source, diets with high (>70%) or low (<40%) percentage of energy from carbohydrates were associated with increased mortality, with minimal risk observed between 50–55%.

- Low carbohydrate dietary patterns that replaced carbohydrate with animal-derived protein or fat were associated with greater mortality risk, whereas this association was inverse when energy from carbohydrate was replaced with plant-derived protein or fat. These findings were also corroborated in the meta-analysis.

- However, there is still no apparent consideration of the quality of the animal and fat intake. Higher carb diets that are based upon unhealthy foods, have not performed well. The same likely holds true for lower-carb diets that are based upon unhealthy foods (ie the original Atkins). Christopher Gardner’s DIET FITS study was a powerful illustration of how either diet will produce favorable outcomes when based upon the whole, fresh and unprocessed foods and including a general intake of fruit and vegetables. We might be throwing the baby out with the bathwater here.

- Authors did control for many confounding variables (age, sex, race, education, activity level, caloric intake, smoking, and diabetes. But, no mention yet of animal protein quality

- We analyzed the covariates of age, sex, race (self-reported), study centre, education level (grade school, high school without diploma, high school graduate, vocational school, college graduate, graduate school or professional school), cigarette smoking status (current, former, never), physical activity level (sport and exercise activity and non-sport activity during leisure from Baecke questionnaire17), total energy intake (kcal), ARIC test centre location, and diabetes status (defined on the basis of use of anti-diabetic medications, self-report of a physician diagnosis, fasting glucose value ≥126 mg/dL or a non-fasting glucose of ≥200).

- We adjusted the ARIC analyses for demographics (age, sex, self-reported race), energy intake (kcal per day), study centre, education, exercise during leisure activity, income level, cigarette smoking, and diabetes.

- It is interesting to note that those who smoked tended to have a higher intake of animal fat and protein, this is why the controlling/regression analysis is important. This data point suggests healthier users were following a plant-based diet, remember this does appear to have been controlled for in their data analysis. See data table below

- The animal-based diets were consumed by those who had poorer lifestyle practices

- Mean carbohydrate intake was 48·9% (SD 9·4). Participants who consumed a relatively low percentage of total energy from carbohydrates (ie, participants in the lowest quantiles) were more likely to be young, male, a self-reported race other than black, college graduates, have high body-mass index, exercise less during leisure time, have high household income, smoke cigarettes, and have diabetes.

- Even after adjusting for this ‘healthy-user’ effect there was still appeared to be a risk from eating an animal-based diet (loosely termed).

- highest risk of mortality was observed in participants with the lowest carbohydrate consumption, in both unadjusted and adjusted models

- Here is a problem, the diets of the lower carb and animal-based dieters appeared less healthy because they contained lower intake of fruits and vegetables. This matters!

- the animal-based low carbohydrate dietary score was associated with lower average intake of both fruit and vegetables

- Low carbohydrate diets have tended to result in lower intake of vegetables, fruits, and grains.

- Just to be clear, the association works the other way also – higher carb diets might not be as bad as previously thought. The reason some data shows them to be unhealthy may be due to poor food quality.

- On the other end of the spectrum, high carbohydrate diets, which are common in Asian and less economically advantaged nations, tend to be high in refined carbohydrates, such as white rice; these types of diets might reflect poor food quality and confer a chronically high glycaemic load that can lead to negative metabolic consequences.

- **Maybe the most important line of the study**

- Our findings suggest a negative long-term association between life expectancy and both low carbohydrate and high carbohydrate diets when food sources are not taken into account.

Authors Conclusion:

- “Both high and low percentages of carbohydrate diets were associated with increased mortality, with minimal risk observed at 50–55% carbohydrate intake. Low carbohydrate dietary patterns favoring animal-derived protein and fat sources, from sources such as lamb, beef, pork, and chicken, were associated with higher mortality, whereas those that favored plant-derived protein and fat intake, from sources such as vegetables, nuts, peanut butter, and whole-grain breads, were associated with lower mortality, suggesting that the source of food notably modifies the association between carbohydrate intake and mortality.”

Interesting Notes:

- There are data on both sides of this argument

- Results from meta-analyses that included several large cohort studies in North America and Europe have suggested an association between increased mortality and low carbohydrate intake (8,9,10,11,12).

- However, the 2017 Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study, of individuals from 18 countries across five continents (n=135 335, median follow up 7·4 years, 5796 deaths), reported that high carbohydrate intake was associated with increased risk of mortality (13).

Clinical Takeaways:

- A low or high carbohydrate diet is unhealthy when food quality is not considered.

- With high food quality, either diet can improve health – see DIET FITS trial.

- What to tell your patients:

- We have flexibility regarding your carb intake, as long as we focus on healthy, fresh and unprocessed foods, with ample intake of vegetables and fruits.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

Overall this was a great study and one that should be included in discussions on diet. The researchers did an excellent job to control for confounding variables of the healthy user effect. However, there is one miss here and that was consideration of food quality. It could have included grass/grain-fed and pastured options.

If confronted with a patient claiming this paper proves low carb diets are bad for you, you are now armed with the knowledge to discuss the important oversight of food quality.

Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet as Part of a Multi-Disciplinary, Supported Lifestyle Intervention for Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis.

Cureus. 2019 Apr 27;11(4):e4556. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4556.

Study Purpose

- Assess the impact of the autoimmune paleo diet plus community support in those with Hashimoto’s.

Intervention

- 17 female subjects went on the AIP + had health coaching community support, for 10 weeks. Note: many of these patients were already eating gluten-free and/or a paleo-like diet

- Some participants even reported previous attempts at the AIP dietary protocol for fewer than five days, given the lack of education about the dietary approach, support services, and communal accountability as well as the overall challenge in preparing 100% AIP-compliant meal

Main Results

- Experienced improvement in symptoms, inflammation (minor effect) and weight (average 6-8 lbs)

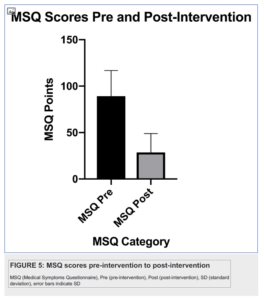

- The clinical symptom burden, as measured by the MSQ, decreased significantly from an average of 92 (SD 25) prior to the program to 29 (SD 20) after the program.

- Inflammation, as measured by hs-CRP (n = 14), was noted to significantly decrease by 29% (p = 0.0219) from an average of 1.63 mg/L (SD 1.72) pre-intervention to 1.15 mg/L (SD 1.31) post-intervention.

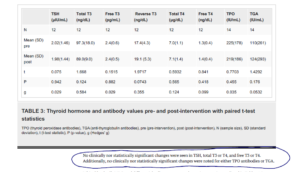

- No change in thyroid antibodies or thyroid hormone levels

- There were no statistically significant changes noted in any measure of thyroid function, including TSH, free and total T4, free and total T3 (n = 12), as well as thyroid antibodies (n = 14).

- There were no statistically significant changes noted in any measure of thyroid function, including TSH, free and total T4, free and total T3 (n = 12), as well as thyroid antibodies (n = 14).

- Community effect vs diet’s effect

- both diet and community appeared to contribute to improvements in this group

- but the community effect should be recognized as highly impactful and might buffer the difficulty of implementing dietary changes.

- Despite prior work indicating that quality of life could be negatively impacted by restrictive diets, this study suggests that quality of life was not negatively impacted but markedly enhanced

Additional Results

- 6 pts able to decrease their dose of thyroid medication. Note: in my opinion, this could be due to gut health and or to weight loss (more likely gut health, in my opinion).

- While there were no observed changes in mean thyroid laboratory markers and antibodies, six out of 13 women (46.1%) who were taking thyroid replacement medication at the beginning of the study actually decreased their dosage of hormone replacement medication by the end of the 10-week study period

- Gradually working up to the AIP diet, instead of starting all restrictions at once, seemed to improve compliance.

- Qualitative post-intervention surveys additionally appear to indicate that the study participants received a positive benefit from the gradual nature of the dietary eliminations, the consistent support from the multidisciplinary team, and the ability to interact with other participants making the same dietary and lifestyle changes

Limitations

- “Limitations to the study include its small sample size, the lack of a control group, the lack of blinding, the possibility for selection bias of participants enrolling in the study, as well as response bias from participants regarding their weights.

- Additional limitations include the use of a medical symptoms questionnaire that has yet to be validated in large populations as well as the potentially transient nature of the participant’s symptoms being documented by the questionnaire.”

Authors Conclusion

- “Our study suggests that an online diet and lifestyle program facilitated by a multidisciplinary team can significantly improve HRQLand symptom burden in middle-aged female subjects with HT. While there were no statistically significant changes noted in thyroid function or thyroid antibodies, the study’s findings suggest that AIP may decrease systemic inflammation and modulate the immune system as evidenced by a decrease in mean hs-CRP and changes in white blood cell (WBC) counts.

- Given the improvements seen in the HRQL and participants’ symptom burden as well as markers of immune activity and inflammation, further studies in larger populations implementing AIP as part of a multidisciplinary diet and lifestyle program are warranted.”

Clinical Takeaways

- The autoimmune paleo diet may or may not be needed for those already on a healthy and gluten-free diet.

- Subjects in this study did not see improved autoimmunity. However, they did see improved symptoms, weight and some even required less thyroid medication.

- If these effects were predominantly due to diet, community support or both are hard to determine.

- Community support may reduce the difficulty of making a dietary change.

- Gradual initiation of dietary changes may improve compliance.

- What to tell your patients:

- Even though the autoimmune paleo diet contains the term autoimmune, does not mean it is necessary or the best diet for autoimmunity. One study found no improvement in Hashimoto’s after using the AIP diet. However, these patients were already on a somewhat healthy diet, and the subjects did feel better. If you like to try to diet we can, if you feel it will stress you out, then there is no need to.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

Very proud of one of our readers, Dr. Robert Abbott for publishing this study. It provides many valuable insights as listed above. The main point, for me, is to use this to prevent your patients/clients from jumping to the most restrictive diet just because they have an autoimmune condition(s). For example, one might be better served by a low FODMAP diet. Personalization of the diet should be the primary aim, and not vacuously following a diet because of how it was named.

Also, the power of community has again been reverberated via this study. Something we should all be mindful of in our practices.

Rob, great work!

Iron deficiency without anemia – A clinical challenge

Clin Case Rep. 2018 Apr 17;6(6):1082-1086. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1529. eCollection 2018 Jun.

Study Purpose

- The only sign of iron insufficiency could be low normal ferritin.

Intervention

- Soppi presents two case studies, which you can read in this paper, access is free.

- In short, all other blood markers were normal. Ferritin was low. Iron supplementation and thus improved ferritin levels resolved the symptoms in both cases.

Main Results

- Below I have listed some tips for managing low ferritin from Dr. Soppi

Authors Conclusion

- One should always consider iron deficiency (without anemia) as the cause of persisting, unexplained unspecific, often severe symptoms, regardless of the primary underlying disease. The symptoms of iron deficiency may arise from the metabolic systems where many proteins are iron containing. Long-standing iron deficiency may be challenging to treat.

Interesting Notes

- Low ferritin might be the only blood finding

- “Iron deficiency may be severe despite a normal hemoglobin and full blood count. Symptoms which may be prolonged and debilitating, should raise a clinical suspicion on iron deficiency even if full blood count is normal.”

- “Ferritin (<30 µg/L) is most sensitive and specific indicator of iron deficiency, although its pitfalls need to be taken into consideration.”

- “Iron therapy should be monitored with repeated ferritin determinations with a target ferritin concentration of >100 µg/L and carried out until symptoms have resolved.”

- Iron deficiency might affect up to 20% of menstruating women

- “Some 10–20% of menstruating women have iron deficiency, and 3–5% of them are frankly anemic [4].”

- “The serum ferritin concentration (cut off <30 µg/L) is the most sensitive and specific test used for identification of iron deficiency [2, 3].”

- “Weakness, fatigue, difficulty in concentrating, and poor work productivity are nonspecific symptoms ascribed to low delivery of oxygen to body tissues and decreased activity of iron-containing enzymes [2,3,11,12,13]”.

- Symptoms may occur solely due to low ferritin

- “The multitude of symptoms is commonly associated with low ferritin concentration without anemia [1,17,20,21,22].”

- “The findings suggest that iron deficiency without anemia (IDNA) may be a risk factor for anger, fatigue, and tension in women of childbearing age.”

- “Patients with repeatedly low ferritin will benefit from intermittent oral substitution to preserve iron stores and from long term follow-up, with the basic blood tests repeated every 6 or 12 months to monitor iron stores.”

- “Our study implicates a possible association between fibromyalgia (FM) and decreased ferritin level, even for ferritin in normal ranges. We suggest that iron as a cofactor in serotonin and dopamine production may have a role in the etiology of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS).”

- “Recreational athletes should be screened for iron deficiency without anemia using serum ferritin, serum transferrin receptor, and Hb.”

- “These meta-analyses suggest that improving Fe status may decrease fatigue.”

- “In addition, iron supplementation has been shown to improve fatigue and physical performance with low ferritin concentration [23,24,25].”

- “Intravenous administration of iron improved fatigue in iron-deficient, nonanemic women with a good safety and tolerability profile.”

- “Daily iron supplementation significantly improves maximal and submaximal exercise performance in women of reproductive age (WRA), providing a rationale to prevent and treat iron deficiency in this group.”

- “Our results demonstrate promise that intravenous iron objectively improves fatigue and quality of life in young women with iron deficiency and mild/no anemia.”

- “Iron should be administered much longer, on average 6–12 months, than only a few months, which is common practice in general care [3].”

- Long term iron deficiency increased the risk of future deficiency

- “If the patient has apparently had iron deficiency for more than [5]–10 years, the ferritin concentration may repeatedly drop with the reappearance of symptoms when oral (Fig. 1) or intravenous (Fig. 2) iron therapy is discontinued.”

- Issue routine follow-ups once ferritin is normal

- When the patient is symptomless, he/she should be followed for an extended period of time to ascertain that the ferritin concentration remains stabilized,

Clinical Takeaways:

- Low ferritin (<100 ng/mL) might be the only sign of iron insufficiency

- Longer-term supplementation and follow up should be considered

- What to tell your patients:

- Your ferritin is not abnormally low, however, some evidence suggests that the low normal value may cause fatigue, poor focus and reduced productivity. We can supplement you with iron until your levels are above 100 and then reassess.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

Many narrow functional medicine lab ranges seem questionable. They lack sufficient outcome data to support their use and are rather inferential. What is so interesting about ferritin is we at least have some preliminary outcome data. I am currently experimenting with supplementing patients’ ferritin to over 100. This is a body of research to keep your eyes on.

If you have found this information helpful please share with a friend using this link: https://drruscio.com/review/

I’d like to hear your thoughts or questions regarding any of the above information. Please leave comments or questions below – it might become our next practitioner question of the month.

Like what you’re reading?

Please share this with a colleague and help us improve functional medicine

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!