Practitioner Research Review – January 2019

Dr. Michael Ruscio’s Monthly – Future of Functional Medicine Review Clinical Newsletter

Practical Solutions for Practitioners

In Today’s Issue

Research

- Dr. Ruscio’s Review of Zonulin Testing for Leaky Gut

- Re-challenging FODMAPs: The low FODMAP diet phase two

- Rapid-Fire Research – Ultra-concise summaries of noteworthy studies

- Autologous stem-cell transplantation in treatment-refractory Crohn’s disease: An analysis of pooled data from the ASTIC trial

- Selective expression of histamine receptors H1R, H2R, and H4R, but not H3R, in the human intestinal tract.

- Using Hashimoto thyroiditis as the gold standard to determine the upper limit value of thyroid stimulating hormone in a Chinese cohort.

- Blocking nocturnal blue light for insomnia: A randomized controlled trial

Research

*Please note: the case study and research studies are not meant to be mutually reinforcing. There is often concept overlap, however, the research studies are a collection of the most clinically meaningful research that has been published recently.

Dr. Ruscio’s Review of Zonulin Testing for Leaky Gut

Study Purpose

- Given the recent study we discussed suggesting that serum zonulin testing is likely not ready for routine clinical practice, I wanted to have a closer look at what the evidence here says.

Intervention

- My review of the literature with editorial; non-systematic

My Conclusions

- Perhaps the most important aspect is that current zonulin testing (stool or blood) may detect proteins other than zonulin, therefore, making the testing inaccurate

- “In conclusion, based on our data we suggest that the Immundiagnostik ELISA kit supposedly testing serum zonulin (pre-HP2) levels could identify a variety of proteins structurally and possibly functionally related to zonulin, suggesting the existence of a family of zonulin proteins as previously hypothesized (42), rather than a single member of permeability-regulating proteins. Along these lines, studies that have used this ELISA kit for zonulin/preHP2 as a marker for intestinal permeability need to be interpreted with these findings in mind. Additional studies are necessary to establish the primary target proteins (zonulin, properdin, and/or other structurally similar proteins) detected by this commercially available ELISA.” [1]

- This is why you are seeing some labs relabel the serum ‘zonulin’ test as ‘zonulin family peptide’. Remember it is unclear what level of ‘zonulin family peptide’ should be considered elevated versus normal.

- ‘Zonulin’ stool tests also do not measure zonulin, nor do they appear to measure the same ‘zonulin family peptide’ that the serum testing measures. So, its fair to say we know even less about ‘zonulin’ stool testing, and that it is more accurate to say ‘zonulin’ stool testing may detect other functionally related proteins for leaky gut. Most likely ‘mannose-associated serine protease family’.

- This is likely why Aristo Vojdani has made the following comments [2]

- *Stool measurements of zonulin are not useful*

- “Regarding stool measurements of zonulin, if a person has a leaky gut, the antigen will be released into the blood. So, I really don’t understand how zonulin is supposed to get into the stool. Perhaps the labs are actually measuring cross-reactive molecules. So, stool measurements are not a useful test in my opinion.” …

- Vojdani makes the same criticism I have made many times – many functional medicine labs rush to a lab marker and reference range before taking adequate time to ensure clinical meaning.

- In my opinion, it seems that these laboratories are using the reference ranges recommended by the manufacturer’s kit, which are indicated as being for research purposes only. The law says that because this kit is only for research, the labs must establish their own reference ranges by running 120 or more samples from healthy subjects. This whole field is, unfortunately, suffering from many such problems. Laboratories are reporting results before going through the extensive validation steps required by law. So, to answer your question, in my opinion, zonulin levels or LPS levels in the blood versus antibodies are two different stories.

- At least antibodies are stable in the blood for 15–30 days or even longer. In my own recent study published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology [3], I found that due to fluctuation, a single measurement of zonulin levels is not recommended for the assessment of intestinal barrier integrity. Instead, the measurement of IgG and IgA antibodies against zonulin is proposed for an accurate evaluation of intestinal barrier integrity. Therefore, I recommend the antibodies, and hopefully, we will have more research in this field.”

- *Stool measurements of zonulin are not useful*

- This is likely why Aristo Vojdani has made the following comments [2]

Continuing my conclusion

- Commercial zonulin testing suffers from poor accuracy (My note: likely due to fact that the testing detects a number of related proteins and not solely zonulin) [4]

- “There was a poor correlation between the results of the two commercially available assays. … Rather than support a role for zonulin in intestinal disease pathogenesis, these results cast doubt on the validity of commercially available zonulin assays.”

- Preliminary evidence suggests that antibody testing may be a more stable measure, but this still needs to be confirmed with further study. [5]

Even though the available evidence may be flawed, what does it say?

- The totality of the evidence does appear to support that serum ‘zonulin’ testing correlates with symptoms or disease activity. Most of these studies have used serum rather than a stool.

- There is equivalent data showing treatment does versus does not affect ‘zonulin’ levels.

- See the preview below or click here to view and/or download the full reference table.

- See the preview below or click here to view and/or download the full reference table.

- So, in short, currently available testing appears to correlate with disease/symptoms but does not correlate well with symptom/disease improvements post-treatment.

Clinical Takeaways:

- It is likely best to wait until we have better data regarding ‘zonulin’ testing.

- For those wanting the most generous possible interpretation, consider ‘zonulin’ testing (perhaps better to use serum) as follows

- Motivated/high resource patients: Pre and post to determine if the gut-health endpoint has been fully reached, but interpreted cautiously.

- Non-motivated/low resource patients: No testing. Or, end-phase to determine if any additional gut therapies should be employed in a preventative fashion, for preventing a disease that may be a consequence of silent GI dysfunction/silent leaky gut.

- Remember, the most compelling data suggest that zonulin testing is not needed at all. Why? First, it may not be accurate. Even using the most liberal interpretation of the data: while it may correlate with disease/symptoms, it may offer no insight in how or how much to treat a patient since a tenuous correlation between treatment and ‘zonulin’ levels has been established thus far.

- Here is an example of what can happen when relying on testing that has not been fully validated. [6]

- A paradox emerges wherein there is an association between elevated ‘zonulin’ and weight gain/metabolic excess, however diets that were effective for weight loss, fasting glucose, etc. paradoxically increase zonulin.

- Perhaps those with higher zonulin are more prone towards weight gain, but their weight can improve independent of changes in zonulin? Perhaps those with increased GI-immune reactivity to foodstuffs experience both higher zonulin and body weight as a result. However, the ‘leaky gut’ is less important for weight loss than is a reduction of foods rich in calories and/or carbs. Perhaps, zonulin is part of this picture in a non-causal way?

- Or perhaps this is due to flaws of the testing, namely the disparity between what serum ‘zonulin’ and fecal ‘zonulin’ are actually testing.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

I have not been using zonulin in my practice mainly because I am unclear on how this data impacts treatment in any way. Even if the testing was accurate, which it appears not to be, how do you treat someone’s gut any different/better based upon this? And, since leaky gut is always occurring secondary to something else (stress, lack of sleep, dysbiosis, poor diet, IBD, infection) which can all be directly assessed, I see leaky gut testing as quantifying symptoms of underlying dysfunction.

You could make the argument that leaky gut testing could be used in a predictive/preventative way, which I am open to. However, in a sick patient reporting to a doctor’s office, this is moot. That said, it is possible there could be someone with silent GI inflammation that possibly could be assessed via zonulin… hence my probe. Like I have said many times when you pull on the string of many theories in functional medicine you quickly see what unravels is minimal evidence combined with spin and hyperbole. Half the game in practice is knowing what not to do.

Finally, I plan to watch the data on serum antibody testing and if/when this is shown to be reliable and predictive then I will likely start using in practice routinely. Until then, I will generally avoid using a test that is still in the research/discovery phase.

Perhaps zonulin testing could be used for a non-symptomatic person looking for a marker of GI health, as there has been evidence that GI treatments (most namely probiotics) can decrease zonulin. But the data here are still early and often times there is no correlation between treatment and zonulin. So, zonulin should either not be used or used carefully and in conjunction with clinical context and intuition.

Re-challenging FODMAPs: The low FODMAP diet phase two

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28244664

Study Purpose

- Establish best practices for FODMAP reintroduction

Intervention

- Commentary from researchers at Monash University

Main Results

- Long-term (6-18 months) follow up data shows low FODMAP to be helpful in the long term, even if avoidance is only partial.

- One study has specifically assessed long-term dietary intake and level of FODMAP reintroduction in patients with IBS. Follow-up questionnaires provided to 100 patients at 6–18 months following initial education showed that 62% had satisfactory relief on the low FODMAP diet. Of those, 71% continued to have satisfactory relief at 1-year post-reintroduction, and 68% continued to avoid high FODMAP foods at least 50% of the time [8].

- Conversely, if low FODMAP is not helping, don’t continue the diet

- It is key that those who do not respond to the low FODMAP diet should not be encouraged to continue on the dietary restrictions

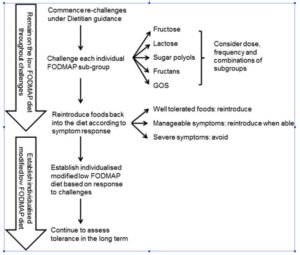

- Essentially the researchers recommend

- Challenging new food, one at a time, over roughly 3 days.

- Foods should be challenged according to subgroups to help hone in on problematic subgroups.

- They also recommend a 2-3 day washout period in between challenges.

- One challenge is completed at a time, often over a 3-day period.

- As a result of the differing physiological effects of FODMAPs in the gastrointestinal tract [10], it is important that each FODMAP subgroup is challenged individually as tolerance to each may vary.

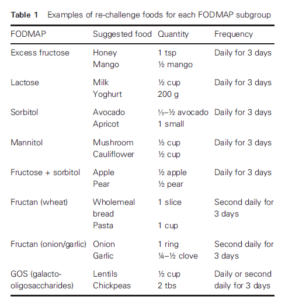

- Table 1 provides example challenge foods and doses for each FODMAP subgroup. The suggested foods only contain significant amounts of one FODMAP sub-group; for example, milk is high in lactose and does not contain any other FODMAP subgroup. Small doses are listed in Table 1 and can be used as a guide, but the dosage used in practice should be adapted to the patient.

- As outlined in Table 1, some challenges may be better tolerated if consumed every second day rather than in consecutive days; hence, the food can be challenged second daily first and, if well tolerated, challenged again across consecutive days

- Between challenges, patients are encouraged to have a 2- to 3-day “washout” to ensure no additive and/or crossover effects occur. Once tolerance to each subgroup is established, patients are encouraged to assess their tolerance to larger doses, increased frequency, and combinations of high FODMAP foods.

- Here is a sample chart of subgroups

- Some logic-based recommendations they provide are:

- 1) Start with the desired foods first

- 2) Avoid foods that are suspect to cause reactions

- They also recommend:

- To avoid foods according to the level of reactivity; highly reactive = highly avoidant for example

- To periodically retest reintroductions as things may vary with time

- An easier approach may be to use the Monash app. Essentially starting with ‘amber’ foods, then working to ‘red’ foods.

- To utilize the Monash University, low FODMAP diet smartphone application [11]. Information within the app is provided using a traffic light rating of “green, “amber,” and “red” serves to represent low, moderate, and high FODMAP content, respectively [11,12,13,14]. “Green” and “amber” foods represent foods containing low and moderate quantities of FODMAPs and are designated as suitable during the restrictive phase of the diet. To assist with reintroductions, patients may gradually increase intake of “amber” serves and assess tolerance. Subsequently, they may increase intake of “red” serves as tolerated to gradually increase total FODMAP intake.

- Remind your patients/clients that some symptoms during reintroduction are normal, and not to be alarmed.

- Patients should also be advised that a certain degree of symptoms is normal (for example, some flatulence or bloating after a large meal are common).

- Some ups/downs along the way are also normal.

- The patient may find symptoms worsen in times of heightened stress, and those functional gastrointestinal symptoms may change over time, hence food tolerance may not remain stagnant.

- These are especially important to offset anxiety, which is more prevalent in those with IBS.

- Finally, anxiety is common in patients with functional bowel disorders (FBD), and hence, the patients’ level of anxiety toward completing food challenges is important to consider.

- Reintroduction is not ‘all or none’. Too large of a dose of FODMAPs doesn’t mean someone might not be OK with a smaller amount.

Authors Conclusion

- While evidence is limited regarding the re-challenge phase, it is an integral part in the dietary management of patients who undergo the low FODMAP diet.

Interesting Notes

- The low FODMAP diet is now included as first-line therapy and has been shown to provide symptom improvement in approximately 68–76% of individuals [1].

- Symptom improvement generally occurs following 3–4 weeks on the restrictive phase of the diet [2], although the length of time required and degree of symptom improvement can vary between patients.

- One study found those on low FODMAP did not end up eating a lower intake of fiber.

- This study did not see any change in the proportion of those meeting fiber recommendations from baseline to follow-up [6].

- Low FODMAP may be less effective for those with constipation.

- However, this study showed no improvement of QOL in those with constipation-predominant or alternating IBS subtypes [7].

Clinical Takeaways

- Low FODMAP can be used in the long term, but a personalized version of the diet is important here.

- Those on low FODMAP might not be eating less fiber.

- There are different reintroduction approaches from meticulous to more relaxed. Clinicians should match the approach to the individual.

- Some reassurance can prevent anxiety in those undergoing the reintroduction.

- This includes:

- the normalcy of symptoms during the reintroduction,

- no ‘all or none’ avoidance being required,

- importance of dose,

- and ups/downs being normal.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

I don’t get highly involved in the reintroduction, but we do provide patients with written resources to assist them. Why don’t I provide detailed coaching on reintroduction? Because I try to focus on what else we can do to improve tolerance to FODMAPs by improving one’s gut health.

That said, I have noticed that patients will tend toward anxiety and the reassurances listed above are important to prevent unnecessary fear and worry. All the above combined with encouragement to listen to ones’ body and I have found patients are very able to execute the reintroduction.

Rapid-Fire Research: Ultra-Concise Summaries of Noteworthy Studies

Autologous stem-cell transplantation in treatment-refractory Crohn’s disease: an analysis of pooled data from the ASTIC trial

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28497755

- In a study of roughly 40 patients, half were treated conventionally and half were treated with autologous stem cells. Results were as follows:

- 3-month steroid-free clinical remission was seen in 38% (13 pts.)

- Complete endoscopic healing was noted in 50% (19 pts)

- Adverse events occurred in 23 of 40 patients

- Conclusion: stem cell therapy “resulted in clinical and endoscopic benefit, although it was associated with a high burden of adverse events.”

Selective expression of histamine receptors H1R, H2R, and H4R, but not H3R, in the human intestinal tract.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16299042

- This study has found that there appear to be 3 types of histamine receptors in the GI tract (H1R, H2R, and H4R) and that there are more histamine receptors found on those with gastrointestinal disease. My note: perhaps H4 antagonists will be developed/discovered and offer recalcitrant patients.

- We have demonstrated that H1R, H2R and, to some extent, H4R, are expressed in the human gastrointestinal tract, while H3R is absent, and we found that HR expression was altered in patients with gastrointestinal diseases.

Using Hashimoto thyroiditis as the gold standard to determine the upper limit value of thyroid stimulating hormone in a Chinese cohort.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27816062

- In short, when TSH was above 2.6 there was a significantly increased likelihood of Hashimoto’s. Authors suggest considering testing for Hashimoto’s in those with TSH above 2.6.

- Joinpoint regression showed the prevalence of HT increased significantly at the ninth decile of TSH value corresponding to 2.9 mU/L. ROC curve showed a TSH cutoff value of 2.6 mU/L with the maximized sensitivity and specificity in identifying HT. Using the newly defined cutoff value of TSH can detect patients with hyperlipidemia more efficiently, which may indicate our approach to define the upper limit of TSH can make more sense from the clinical point of view.

- CONCLUSIONS: A significant increase in the prevalence of HT occurred among individuals with a TSH of 2.6-2.9 mU/L made it possible to determine the cutoff value of normal upper limit of TSH.

Blocking nocturnal blue light for insomnia: A randomized controlled trial

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29101797

- Wearing blue light blocking glasses, improved insomnia compared to placebo. My note: it might be best to avoid TV and/or blue light before bed, however this strategy of wearing glasses could be used if/when this is not possible.

- Wearing amber vs. clear lenses for 2-h preceding bedtime for 1 week improved sleep in individuals with insomnia symptoms. These findings have health relevance given the broad use of light-emitting devices before bedtime and the prevalence of insomnia. Amber lenses represent a safe, affordable, and easily implemented therapeutic intervention for insomnia symptoms.

I’d like to hear your thoughts or questions regarding any of the above information. Please leave comments or questions below – it might become our next practitioner question of the month.

Like what your reading?

Please share this with a colleague and help us improve functional medicine

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!