How to Build Muscle with Body Building Champion Ben Pakulski

Ben Pakulski is a championship bodybuilder who uses his knowledge to help people of all levels get the physique they want. He focuses on keys to ensure your muscles are activating properly. For example, if you don’t have the glutes you want, it could be because they are not fully turning on. Let’s discuss how you make sure your weak points are firing.

Those who are able to maintain muscle mass over a long time will sustain optimal health for longer periods of time.

Fundamentals of Training – Consider two things

- The exercises you are already good at

- The exercises you would require more learning and skill to master

- Do these more often

- In training, you should live below 50% or above 90%

- Most people live in the 70% range

When approaching a glute workout for instance

- Think about how to fully lengthen the glute

- How to get into full hip flexion

- How to load it and create the maximum challenge in that position

Choose a workout that will exercise 3 positions

- An exercise that would challenge a fully lengthened glute

- For example stiff leg deadlift, lunge, or a squat

- Where all the motion is happening at the hip joint

- Then an exercise that would challenge the glutes in a short position

- Like a glute bridge

- Something to challenge glute in mid-range

- Lunge, leg press

Chronically tight muscles explained

- If something is tight it’s usually trying to overcompensate to create stability for something that is weak

- Stretching post workout as a parasympathetic activity is very good for the body

- Yoga is a great tool for stability and mobility

Glute workout progression example

- Increase frequency to 3 times per week minimum

- Then you can reduce frequency eventually to once every 5 days

- Once frequency goes down, volume goes up

Where to learn more

In This Episode

Episode Intro … 00:00:40

Optimizing Body Composition … 00:05:42

Fundamentals of Training … 00:10:00

Glute Workout … 00:19:09

Tight Muscles Explained … 00:25:40

Workout Progression … 00:27:51

How To Access Pakulski’s Program … 00:30:25

Episode Wrap Up … 00:44:06

Download this Episode (right click link and ‘Save As’)

Episode Intro

Dr. Michael Ruscio, DC: Hey guys I’m here with big Ben Pakulski. We’re gonna be talking about how to optimize a number of things, but one will be muscle mass, and if you remember back to the conversation we had with Jeff Moss, gosh, now over a year ago, he discussed that one of the greatest predictors for all-cause mortality was muscle mass and muscle strength. And so if we want to optimize longevity, optimizing muscle mass is one thing that we wanna do.

DrMR: One of the questions I have as we lead in, and Ben if you have any thoughts on this I’d be really curious to hear them, I wonder, are healthier people more prone to having higher muscle mass, and if so, is it a selection bias where people who are healthiest have the highest muscle mass, therefore they have the highest life expectancy? Or is there something about training, and adding that muscle mass, that actually makes someone healthier and therefore increases their longevity?

Ben Pakulski: Speaking with respect to longevity, I don’t know that it’s an adding of muscle mass thing, it’s more of preventing of loss of muscle mass. So those people who are able to maintain muscle mass over the longest amount of time will sustain optimal health for a longer period of time, greater insulin sensitivity, potentially greater overall body function. So I don’t know that it’s a matter of adding muscle mass, although depending on where you’re starting it may be a matter of adding muscle mass

DrMR: Sure. Okay. And how do you want to launch into this conversation? And maybe let’s start with you telling people a little bit about your background, just so I know where you’re coming from. Looking at you, obviously, you’re a very muscular guy.

BP: So a little bit about me, my background, I started off being very unhealthy as a kid. I came from a family of overweight alcoholics and drug addicts, effectively. And I was skinny and fat, and I’ve been a vegetarian, I’ve been everything under the sun when it comes to my health. Around 15 years old I started this endeavor to start adding some muscle mass, like most people, to improve athletic performance, and I really started to love it.

So I started on this 20-year journey to add as much muscle as humanly possible with the objective of being the biggest human being on the planet at one point. That was my laser-focused objective. And along the path, I realized that I had a really hard time building muscle compared to some other guys. So I had to find really creative ways, really intelligent ways, I studied everything that I could. I have a four-year degree in kinesiology, as well as probably 25 different certifications that have followed that.

And from that, you learn to take everything in and extrapolate what’s useful and what’s valuable, what’s opinion you kind of disregard, and from that, I’ve been able to put together a really logical and comprehensive approach to building anyone’s body. And I want everyone to know that regardless of what your excuse is right now as to why you don’t look the way you wanna look, it’s not your genetics, it’s not your time, it’s not even your nutrition. If you learn how to train, effectively, your body will respond the way you want it to. So my training revolves around efficiency and time and making the most of every little detail, whether it be in the gym and outside of the gym.

Optimizing Body Composition

DrMR: Gotcha. Now how do you start wading into this topic of optimizing body composition? Because I’m sure it’s individual, yes, but there’s also probably a few different types of people we can try to give recommendations around. Would you say that’s true? Is there maybe young males may be different than middle-aged females, and so we can maybe give a couple of different categories of recommendations for these different folks listening?

BP: Absolutely, man. I mean, ultimately it all comes down to what you love, what you wanna do, first and foremost. I’m not an advocate or a zealot of anything other than hard work. I put “hard work” in quotations because most people go in the gym and they assume that breaking a sweat and being out of breath is hard work, and I don’t think that’s necessarily the case.

DrMR: Hard but not smart maybe?

BP: Right. So finding things that you love to do and then finding a way to work hard in a safe way that fits your body, right. So most people go to the gym, and guys who are really tall and they can’t build their legs, and they go, “Well I can’t build legs.” And you got guys who maybe have very flat sternal angles and, “I can’t build my chest.” Anyone has an excuse around why they can’t do certain things, they can’t build muscle or they can’t look the way they wanna look. And I think it’s just that. It’s important for people to realize it’s just an excuse. You absolutely can if you learn how to do things effectively for your body and learn how to manipulate your mechanics.

So the simplest framing is, the way you do an exercise and the way I do an exercise is, based on the way we’re built, it’s gonna be extremely different. That doesn’t mean you’re good at something or you’re bad at something, it just means this is what your body is built to do. So if we can now learn to manipulate the execution of exercise to influence your body to do it in a slightly different way, we can start to make your body respond in a different way. We can subject your body to different forces and different angles, now the body’s gonna start to respond in a more effective way. So ultimately we’re looking for the most effective and efficient way to stimulate and challenge your body to create the greatest amount of stimulus and growth with the least amount of negative side effects and time.

DrMR: Okay. And for people listening to this who may not be super fit, per se, but they’re saying, “Yes, I’d like to enhance my body composition.” And as we’re trying to keep these couple of different categories in mind, what are some of the fundamentals? We all probably have heard training frequency, you need to train enough but not too much, you need to try to overload a muscle perhaps and then have some recovery. So what are some, for people who are beginners, because we probably have some doctors listening, some nutritionists …

BP: So, objectively, I think it all starts with how you do something, right. Everyone goes, what should I do? It doesn’t matter what you do, it matters how you do it to start. If I ask you to write your name, but I want you to write it with the opposite hand, it’s gonna take time, you’re going very very slowly and learning a new skill. That’s an important thing for people to realize. People get frustrated that they’re not good at something or they’re not able to do something, and they give up. And the realization is well that’s not the truth, you just haven’t given it enough time to learn the skill.

So no matter what it is, skill acquisition, execution, is the foundation of all progress. So whether you wanna be a basketball player, you gotta learn how to dribble. If you wanna learn how to spring 100 meters, you should probably learn how to walk before you learn how to jog and sprint. So there’s that foundational layer that everyone’s missing is like, learn the skill of whatever it is you wanna do, and then progress it, right.

So if I frame my exercise business around 40 exercises, I’m like, “If you can learn these 40 exercises, you can maximize your body.” It’s five exercises on average per body part, sometimes less. And I think that’s one of the biggest problems people are making, is they’re going in the gym, they’re doing too many things. They’re never good at anything. They suck at them all.

DrMR: So, you would kinda disagree with some of maybe the newer-age functional training from a body composition enhancement perspective? You think that’s adding too much? Or is it serving a different objective?

BP: Well, not necessarily. It’s a different objective. I think the whole term functional is comical. I think it’s misunderstood and misleading because ultimately muscle function is lengthening and shortening. And as long as you challenge a muscle through its full contractile range, the muscle’s gonna maintain its optimal function. So it doesn’t matter necessarily what the exercise transfers into, unless it’s for sports specificity. If I’m training to be better at a specific sport, obviously I need it to match what I’m trying to do output wise. But this whole idea of functional, what are you trying to achieve? Are you trying to be better at a club swing or are you actually just trying to have more functioning muscles, meaning I want them to actually do what I want them to do when I want to do it? And that’s just a matter of challenging a muscle through its entire contractile range relative to what it’s capable of doing.

Fundamentals of Training

So I think that whole functional thing is convoluted and misinterpreted, and people take that term and they kinda make it this broad-stroke statement that can mean so many subjective things. But ultimately muscles are inside your body and muscles are only able to shorten. So if we challenge a muscle that’s fully shortened position, fully lengthened position, and we give it full range challenge, objectively we’ve created a functional muscle because now it’s able to contract at all parts of its contractile range.

DrMR: So we have these 40 exercises, it was five per body?

BP: Give or take. Larger body parts have more, smaller body parts have less, but give or take.

DrMR: So maybe we can tick through these one-by-one because I’m sure women listening to this are thinking about their butt. And so what are some of the keys there?

BP: The way I wanna frame it is, I always give people this very simple framing of, you have certain exercises that you’re already good at. So we have this list of 40 exercises and we’re gonna make a column, and we’re gonna have two sides. One side is this side that I already know I’m really really good at. And we have this other side that I need some time mastering the skill, I need some skill acquisition. So we’ll create this column and the ones that require more time and attention to acquire the skill, we’re gonna spend more frequency with those. So we’re gonna do those more often. Because any time you’re trying to learn a new skill, you need to do it more often, obviously.

DrMR: So, like twice a week rather than once a week or …

BP: More.

DrMR: Maybe more? But it’d be lighter, I’m assuming?

BP: Not necessarily lighter but lower volume. So volume and frequency are inversely proportional. So as my frequency goes up my volume goes down. So it may be as simple as doing 3-4 sets per exercise or per body part, doing it more often, and training your nervous system how to do it. And then we have the other side of this column which is the ones I’ve mastered. And those ones I’m actually gonna use for my output-based exercises. So whether you’re a man or a woman, you need to work hard. And working hard is very subjective. But you need to find the things you’re able to do unconsciously, right. We’re trying to achieve unconscious competence. And if I can do these exercises unconsciously, now I can just focus on work. I can focus on effort, I can focus on output.

And now I can increase my caloric output, I can increase my mitochondrial biogenesis, I can increase my body’s ability to burn fat. So we’re gonna live in those exercises, right. Those ones that I know I’m already good at. They feel good, they don’t hurt, I can do them unconsciously, while we slowly develop this other skillset around those other 40 exercises which are your core 40.

DrMR: Gotcha. I wanna come back to maybe some key movements for glute development. But really quick, you said mitochondria, and I’m wondering because this is something I’m actually personally interested in, is there a certain work rest ratio that you like for a mitochondrial building exercise program?

BP: I haven’t found one yet because it’s so subjective, right. Someone comes to me and a 4:1 ratio may be adequate for them, whereas someone like yourself, maybe a 1:1 ratio. So it’s always progressive like that’s the only way I look at it…

DrMR: I’m sorry, 4:1 would be like four minutes to one minute off?

BP: … rest to work. Yeah, sorry, thank you. And it’s always progressive, and I think the biggest thing people need to acknowledge is just measure. Nothing’s wrong. I think one of the biggest paradigms in fitness that people mistake is they think, well this is the only way to do it, this is the only way to skin a cat. I’m like, no no, it’s all right. It all has varying degrees of accuracy and relevance, but progression is the only way to ensure progress. So okay, if you’re at a 4:1 for this week, let’s stay at a 4:1 this week, and let’s move to maybe a 3:1 ratio next week of rest to work.

My expertise is getting people in world-class competition shape for bodybuilding shows or figure competitions, or fitness competitions. One of the biggest things that I’ve done wrong a lot in my life, and a lot of people do wrong now, is they do too much. So in the stressed world we live in, we’re always in the sympathetic-dominant state. Our body’s just in fight or flight constantly. Your brain is spinning, your email’s blowing up, your phone’s blowing up, you’re driving and you get cut off in the car, you’re flipping people off. So you’re in this massive state of sympathetic arousal. So going in the gym and making a tremendous amount of stress on top of that, in a lot of instances for people it’s causing too much cortisol, too much adrenaline, we’re gonna have a hard time burning fat.

So I try to make this stress a minimum effective dose. So what’s the least amount we can get away with to still make constant progress? So that’s always my framing for everything. It’s never about maximum effective dose. Because the problem with maximum effective dose, if you’re one of those people who “works hard” and your only strategy of progression is working harder, you’re f*****.

DrMR: You’re gonna max out really easily.

BP: Well yeah, and then your stress is gonna override the stimulus, and you’re gonna end up hurting yourself, you’re gonna end up being resistant to insulin, and you’re gonna be resistant to cortisol.

DrMR: So is that something you find that there’s a fair amount of people who are spending too much of their training time, and I mean their days and their weeks … not necessarily their one session in the gym … but too much of their overall training time kind of at that high output end, and they’re not using that minimal effective dose, maybe building up and then recovering?

BP: I think it’s the exact opposite actually. I read about this often is where you should live in training is either below 50% or above 90%, but everyone lives in this 70% range where they’re kinda working hard, but it’s not really hard. They think it’s kinda hard, they #CrushIt today, but it’s kinda like trying to cook a cake on lukewarm temperature. They’re never really hitting that high-end stimulus like that high-intensity exercise place, and they’re never really pulling back and letting their body recover. They’re just kinda always subjecting it to this gray stimulus, and I think that’s a big problem.

So you have this low-level constant cortisol all the time. Just never enough to really create a response or create an adaptation in your body, they never really push it hard ’cause they’re constantly burning themselves out with the mediocre stimulus.

DrMR: That’s really insightful. So, what you’re saying is you need these truncated periods of you’re really pushing hard balanced out by a decent period of a much lower gear.

BP: Yeah. One of the big things that I advocate is learning the skill of working hard. People hear that and they’re like, “That’s obvious,” but it’s not because it takes time to learn how to contract more muscle. It takes time to learn how to actually generate some output, because your body aerobically, anaerobically, muscularly isn’t able to work hard if you haven’t trained that. So, training the skill of hard output takes time for a pro athlete, for anybody.

Sometimes for pro athletes, I’m taking six or eight weeks before I actually ramp them into a workout where we’re actually doing enough work to change their body, but it’s always a progression. Here’s the best way to look at it is, if I go to you, Mike, you’re going to go to the gym tomorrow and you’re going to do 20 sets for legs. How many of those sets are actually going to be max effort? Two maybe? For most people not even. If I go to you and I go, “Hey man, you go to the gym and you do four sets for legs.”

In the first workout, you’re going to probably train the way you always have, and the second workout you’re only getting four sets again. Maybe eventually you start to get a little urgency. You’re like, “Hey man, if I don’t work hard on these four sets, I’m not going to get any results.” So, now you create this urgency around, “I actually have to put maximum effort into every single rep of every single set.” Then, and only then once we’ve learned how to maximize that very small amount of volume, then we can slowly progress it up.

So, most people are, like I said, just going out like a seven at a ten or a six and a half at a ten for these 20 sets. Then they’re like, “I don’t know I don’t get results.” Everyone’s response is, “You need to do more.” You don’t need to do more, you need to do less, but you need to do better and you need to work harder in a short amount of time. It’s almost like reverting back to the Arthur Jones school of thought of a high-intensity training. He had it right, man. He was so far ahead of his time, he was crazy but he was right. I mean, crazy when I say the way he approached it. He was so dogmatic about, “This is the way it’s got to be,” but he really did have it right.

Your objective is I need to create hormetic stimulus in the shortest amount of time in this very high-level amount of stress to the muscle and then walk away. It’s not this long duration stuff that’s going to build muscle if that’s your objective.

Sponsored Resources

Hey, everyone I’d like to tell you about BIOHM, who helped to make this podcast possible. Now, BIOHM offers a line of gut-healing products, including a probiotic, a prebiotic, and a green powder. Now, their probiotic is interesting in the sense that it combines strains from both category 1 and category 2.

So from category 1, you have lactobacillus, acidophilus, lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Bifidobacterium breve. And from category 2, you have S. boulardii, so a nice combination of category 1 and category 2.

And if you go over to BIOHMHealth.com/Ruscio and use the code RUSCIO at checkout, you’ll get 15% off your first order. So BIOHM, they’ve got a good line of probiotic and prebiotic and the greens powder, all to help you improve your gut health, which we know has such massive and far-reaching impacts. So check them out over at BIOHMHealth.com/Ruscio.

Glute Workout

DrMR: In developing that concept of trying to provide a glute workout within that theme of legs, are there certain exercises you would recommend, question one and question two? I know this is maybe challenging because you can’t personalize to the individual, but generally how would progress their volume? If someone’s saying, “Okay, right now I’m doing legs once a week. I do three exercises. I do squats, walking lunges, and I do dead lifts.” How would I change that? I do three sets of each of those once a week. What would be a better way?

BP: The simplest framing for any body part is this, I look at a body part like it’s in thirds. And we have a length in part of the range, we have a shortened part of the range, and we have a mid-range. Ideally, the ideal scenario is you create an exercise that challenges all of them in one, but that’s not always the easiest thing to do. So, specific to glutes, you need to look at, “What’s the function of my glutes, and how do I fully lengthen a glute?” So, how do I get into full hip flexion in this massively lengthened glute, load it there, and create the maximum challenge in the fully lengthened position? That exercise one.

An example of that may be a stiff legged deadlift, bent-over deadlift. It may also be a lunge or a squat. Those are going to challenge my glutes in the lengthened position. Objectively though making sure there’s no movement at my spine, all the motion’s happening at that hip joint. Then the exercises that challenges my glute in the short position would be something like a glute bridge. Then something that would challenge my glute through mid-range may be, again, you could use a lunge, you could use a leg press, effectively most exercises are going to be somewhat mid-range for glutes or any body part.

When you learn to challenge maximum length and range and challenge maximum in the short range, then you actually can get great contractions. That and that alone, if you can improve contractibility in those ranges, your muscles will grow I guarantee without ever having to think about sets, reps, volume and load.

DrMR: For the listeners, the glute bridge, that’s where people lay on their back and have the bar at their hips, and then kind of thrust their hips up.

BP: You’re right. You’d have your shoulder blades across the bench and your feet are flat on the floor with your heels under your knees and taking your hips back down toward the ground, and then thrusting up. For people who understand anatomy, you’re looking for an anterior pelvic tilt to try to get the glutes maximally activated while we thrust hips forward.

DrMR: You weight that with some people?

BP: Yeah, ideally. For most people not though, to be honest.

DrMR: Not initially?

BP: Well, because the muscle is typically so weak in that shortened position, as you know, any muscle. If you have a “weak body part,” meaning it’s underdeveloped, 100% of the time it’s weak in the short position. So, most people who have a hard time feeling their glutes, they’re not going to be able to feel it in that short position because the nervous system just isn’t well developed there.

DrMR: So, at first no weight, just wake it up kind of thing?

BP: Yeah. Honestly, the best way to do it is six to ten-second isometrics, holding it as hard as you can in that shortened position. When I say as hard as you can, it’s very specific contractions rather than max effort contractions. It’s going to be specificity most importantly.

Once you learn how to execute those exercises with precision, and when I say precision it means I can unequivocally say that every millimeter of that set, that muscle is contracting. Most people have this issue where they do an exercise and if you ask them to stop, they can’t in the middle of the exercise. You ask them, “Do you feel it at this point?” They’re like, “Some parts I feel it, some parts I don’t.” For those listeners out there, if you can’t feel it working at every millimeter of the set, you’re wasting your time. So, make sure unequivocally you can say, “Yes, I can feel it here.” If you can’t stop, find the contraction and continue.

There are many levels in there that can help people start to learn how to feel muscles. As you’ll know, the number one governing factor is stability. So, if you lack stability, you don’t stand a chance of contracting the muscle. Maximize stability, and that’s internal. Create internal stability whether it be your trunk or pelvis, pelvic floor or whatever, and then learn how to contract those muscles independently.

DrMR: Okay. So, for the glutes now, you mentioned the glute bridge. Either a squat or a lunge sound like two fundamentals you would recommend pretty much everyone do?

BP: Yeah. Well, yes, but here’s the thing. When people hear a squat, they go, “I can’t do squats. They hurt my back or they hurt my knees,” but they don’t. They shouldn’t if they’re done properly. The thing that I’m a huge advocate of is active range of motion, and you’ll get that as, “What can I actively control?” It’s not like I have this objective of getting my butt to my ankles. I have an objective of taking this hip joint through its full excursion. So, if I can get my hip joint into a maximally flexed position, I know the glute is fully lengthened. It doesn’t matter where I am in space if my hips are on my butt. It doesn’t matter. All that matters is that I’ve created the greatest amount of hip flexion and the greatest amount of distance from my center of mass.

So, anyone who wants to understand what that means, if I’m standing up straight, all my body is balanced through my center of mass. So, the middle of my foot, my knee, my hip, my shoulder are all stacked. As soon as I take any of those joints away from that center of mass, those muscles become more challenged. The muscles that cross the joints will have to work harder to stabilize and move those muscles. So, the further I can get my hips away from my center of mass, the more those muscles across the hips have to work.

So, for those ladies out there or guys who want to learn how to challenge their quads or their hips, learn how to manipulate distance. If you can take your hips further back from that center of mass as far as you can, obviously without losing your balance, that’s going to be your greatest opportunity to challenge that muscle.

DrMR: The glutes specifically, right?

BP: Well, if it’s the quads, you would go the opposite way. You’d drive your knees as far forward as you can within reason for the health of your joint and what you’re capable of doing based on stability. But yeah, specific to the glutes, driving those hips back. Find the greatest amount of range of motion at the hip joint. Most people can achieve relative challenge to the muscle without hurting themselves. There’s stuff, if you have back issues, sure, great, we’ll have to make some amendments. On mass, you can do these things, you just have to learn how to figure out how to do them for your body and then progress them.

So, if you lack mobility, if you have lower back pains, if you lack hip mobility, if you have “tight hamstrings,” it’s because you lack strength and you lack stability. People wonder, “Well, I have genetically tight hamstrings ” No, you don’t. You’re weak.

Tight Muscles Explained

DrMR: Can you expound upon that? That’s something I’ve heard, I haven’t had a chance to fact check, but it’s always made sense to me. Actually, the first person I heard say this was Paul Chad talking about tight hamstrings actually being weak hamstrings that are just kind of trying to compensate for the weakness by becoming tighter. Can you explain how that works?

BP: It could also be weak rec fem. So, think about it as a protective mechanism. If I’m trying to go into hip flexion… Typically the way the body works is it moves actively. So, we have active and passive motion. If we move actively, that means something is actually contracting to pull me there. So, an example being, if I’m bending over to do a dead lift, which is like a hip hinge type movement, I’m bending over at the hips, my spine is locked. I come to this point where I can’t go any further.

Well, you could look at it like, “Well, I can’t go any further because I have tight hamstrings,” or you could look at it like, “I can’t go any further because the muscle in the front, the rec fem that should be pulling me over isn’t strong enough to continue to pull me into flexion. Thereby the hamstrings have tightened up as a protective mechanism to prevent me going further,” because it’s just your body is trying to keep you safe. So, that’s the thought process is if something is tight, it’s usually trying to overcompensate to create stability for something that is weak in that area.

Subjectively, we don’t know exactly what. It could be the hamstrings, as Paul says, and it could be the rec fem. It could be some other internal hip muscles. It’s something. The best way to look at it is, when you walk on ice, what happens? You tighten up, right? So, your brain senses instability and it automatically tightens you up to keep you safe. The same thing is happening, your brain is designed to keep you safe. If that muscle was loose and you didn’t have the ability to actively control that range of motion, you’d hurt yourself. So, your brain is tightening as a protective mechanism to prevent muscle injuries.

DrMR: So, do you think stretching is a bit overrated?

BP: Not at all. I just think it’s misunderstood. I think stretching is extremely valuable when done correctly in the right times. I don’t think it’s useful pre-workout. I think it’s reckless pre-workout. I think it doesn’t make any sense. Post-workout as a parasympathetic activity, it’s beautiful. I think it’s great to connect with your body, to connect with your nervous system, to relax. Later in the day before bed, I think it’s a great thing. I’m a big advocate of yoga. I do yoga three or four times a week, although it doesn’t look like it.

I don’t see yoga the same way most people do it. I see it as an opportunity to increase stability and parasympathetic stimulus in these extremely uncomfortable positions and learning to calm your mind. Stability and mobility, stretching is a massive tool, but I think it’s misunderstood.

Workout Progression

DrMR: Gotchya. Okay. How would you progress, coming back to the same example we’re trying to build, how would you progress a glute workout for someone trying to develop their glute muscles?

BP: Okay. First and foremost, as I said, the foundation is in how you do it, not what you do. So, let’s make sure we’re doing things correctly. For most people to do things correctly, it’s increased frequency. So, we may be doing things because it’s a large muscle group and you’ll be doing things three times a week. The best example is we’re going to learn how to speak Chinese, Mike. You and I are going to learn how to speak Chinese. We’re going to do it once a week. How much retention are we going to have? Terrible. So, let’s do it three times a week minimum, and you could even do it more. You’ve got to realize when you have these muscles that you can’t feel or aren’t developed very well, typically your ability to contract those muscles from a nervous system perspective is poor. So, when you actually contract them, even though we’re “working hard” in our mind, our perception is high, the actual muscular contractibility is low. So, we want to do it more often, so we train the nervous system, we train the body to do it more often to become better at it.

Once we’ve achieved that skill of execution and contractibility, progression then goes from increased frequency to slowly decreasing their frequency. So, it may go from three times a week to twice a week. Then maybe we go to every five days. I don’t think any less than every five days is useful. I think the whole bodybuilding mentality of once a week is under-valuable for most people. It’s not the most ideal scenario, so a minimum of every five days. Then as frequency goes does, volume goes up. So, from doing something twice a week, I’m going to do more sets and reps than if I was doing it three times a week.

The best way to think about it is over three workouts if I was doing 15, or let’s say 21 sets, now I could do those same 21 sets in two workouts instead of three, condensing a little bit. That’s just an arbitrary way to explain it. So, now we’re just decreasing the frequency, increasing the volume and progressing that way, always making sure that your foundational principle is, “I need to maximize execution,” because if it’s not there, it doesn’t matter how much weight I have on the bar. It doesn’t matter how many reps I do or how many sets I do, because it’s just diluting the stimulus. We need to learn to concentrate the stimulus on that one muscle because realize our bodies have evolved to cheat. Our bodies have evolved to make things easy.

So, we need to learn to eliminate all those other surrounding muscles that want to help, that have evolved to help, and we need to learn to concentrate the stimulus on this one area. So, that has to be the foundational principle of everything we do, because doing more but doing it worse doesn’t end up with better results. It ends up with more stress and less actual results.

How To Access Pakulski’s Program

DrMR: Now, how do people get access to this coaching? Do you need to have someone there with you, or is there a way to do this without a person right there watching you?

BP: I mean, that’s the ideal scenario of course. I’ve got tons of videos out, and the way I teach is just like the way I speak is like nothing is concrete. I’m going to look at you, let’s see what happens. I’ve been able to break it down into three basic body types. If you can teach principles, I just love the idea of teaching principles. In nutrition and in fitness, I’m not teaching people in concretes like, “You need to eat no carbohydrates, man. You’ve got to go keto.” I think it’s dumb. I think who, what, when, how. So, it’s the same in training. Anyone who’s dogmatic about anything, I would strongly consider walking away from.

DrMR: I’ve said the same thing many a time, yep.

BP: Who, what, when? What’s the scenario? What’s my goal? What’s my body capable of recovering from? Where are my stress levels? So, I think just the way that I frame it is I want to teach you guys principles so like, “Hey, look at this. Look at this muscle. What does this muscle do, and how do we challenge that?” It’s so much simpler than you think. You don’t have to have anatomy background or a kinesiology background. You just have to have a thought. The biggest thing, the number one thing I say when people walk into my facility or walk into my online world, is I say, “Forget everything you think you know about exercise and think,” because a bench press is not the best exercise for your chest. The squat is not the best exercise for your legs. A deadlift is not the best exercise for your glutes. It absolutely depends who you are, what you look like, what your current goal is because a bench press may be an amazing exercise for me. A squat may be an amazing exercise for you. But if you’re doing a bench press, you might get sore shoulders. I might get huge pecs. What’s the difference? That doesn’t make you a bad person. It doesn’t mean you have bad genetics. It just means you haven’t learned to set up for your body yet.

DrMR: So in the online program that you have, would someone who knows little to nothing about exercise be able to plug in and figure out if they should…

BP: Absolutely.

DrMR: So is there a self-assessment that you do? Or how do they get there?

BP: No. I’ve created a framing around what I call primary workouts, which is like priming your muscles for growth. You go through this four to six week phase of learning how to do these exercises, and it’s framed around the output exercises and the skill exercises, like the skill acquisition exercises. But really it’s just like … I think I do a pretty good job now of getting in front of the camera and going, “Hey, I want you to think about this, and walking them down the path of like, “Here’s what you need to do to feel this exercise, and if you don’t feel this exercise, here’s how you troubleshoot, and here’s the best cues to optimize your execution on this, and here’s what you should be thinking about.”

DrMR: So it’s not something where you necessarily need to coach with you watching every inch of every rep. But rather, there’s just some basic fundamental, cues that you’re referring to.

BP: Would definitely expedite it because realize that when people start to execute things, and as soon as you put a load in your hand, everything goes out the window, right? If you can execute it perfectly with no weight in your hand, that’s a great start. Put a weight in your hand, everything goes out the window because your brain then shifts its focus to what’s in your hand. So it’s definitely a great way to accelerate the journey. Unfortunately, most coaches don’t know what the hell they’re doing, as far as when it comes to actually understanding biomechanics.

We started doing live events, which are really successful. But really, your foundation is finding somebody who knows what they’re doing and making sure that they’re objectively challenging muscles, not challenging exercises, because if your objective is to build a great body … If you want to get good at an exercise, if you want to get good at a kettlebell swing, that’s a completely different thing, right? If I want to learn how to challenge my muscles and actually improve my body’s ability to function, improve my physique, what needs to be an internal focus?

So I need to focus on what the muscle is doing, and then how do I most efficiently and effectively challenge that muscle. So there’s no exercise focus, right? You have muscle-centric and exercise-centric, and we’re very muscle-centric. So I want to learn what this muscle does, and then how do I challenge it at every inch of this rep? Not just like, “Do this exercise. I know it’s working my quads or my glutes.” It’s like, “No, no, no, no, no. That’s not enough. It needs to go deeper than that.” It needs to go like, “Slow down. Make sure this is contracting at every inch of the range and make sure you’re giving it maximum challenge,” because you know what your body does when things get hard is you try to accelerate and get the hell out of there. So you have to say no like, “Where does this exercise giving my greatest challenge and how do I spend time there as much time as possible to get the greatest amount of results?”

View Dr. Ruscio’s Additional Resources

DrMR: Are there certain muscles that you find are commonly problematic for men or for women? Commonly weak, commonly not activated? I mean, I’ve heard glute, glute max, glute med. What do you see if any patterns?

BP: Well, hamstrings for everybody typically because we sit so much, and people don’t train them properly. That’s basic. Every guy in the world lacks a chest because he’s got poor posture and lacks the scapular retraction ability to actually contract his pecs.

DrMR: So funny there, you say the pecs, and I think most guys are thinking about just blasting their pecs. I’m guilty of this myself.

BP: You get sore shoulders.

DrMR: You go to the gym and you bench, bench, bench, bench, bench. But it may be a scapular… This is something I’ve heard Poliquin say also that part of your bench output is limited by your scapular retraction.

BP: Not part of, all of it. If you’re trying to contract your pecs, it is governed by your ability to stabilize your scapula. So if you can’t keep your scapula back, you don’t build your pecs.

DrMR: So a weak bench that won’t go up oftentimes comes back to the scapula?

BP: Well, I don’t look at it from a loading perspective because when we look at it from a loading perspective, there’s a lot of things that can contribute to that, right? I could get stronger shoulders. I could get stronger triceps. All of those things can contribute to increased load. That’s different. If I’m looking at challenging the pecs exclusively, it has to be governed by scapular retraction. If I can’t keep my scapula back, and most people can’t even do it without any weight.

As soon as you add weight in their hand, it goes out the window. So if you don’t have the ability to retract and maintain retraction and slight depression of the scapula, you can’t build your pecs. So I get people that walk into my facility, and they say, “I want to build my chest.” I’m like, “Okay, let’s go train your back,” and they think I’m out of my mind. But one of my favorite quotes that I use of all time is sometimes for some people, not everybody, but the best chest exercise is properly executed back exercise.

The cool thing about it is it’s such a short amount of time. We could do it in two days, and all of a sudden your chest is working completely different like, “Oh my God. I’ve never felt this before, like this in my life,” and it’s life-changing. People go, “Wow, I wish … I’d been working for the last 10 years, I didn’t get any results in my chest, or I get sore shoulders, or I can’t build my upper pecs.” I’m like, “Well, of course, you can because you can’t retract,” and that all starts, as you know, with posture. If you’re in a thoracically flexed posture all the time, you can’t have retracted scapulas.

And then posture starts in breathing, and it’s this whole chain reaction. Like if your breathing is shallow and through the mouth, well, you’re not going to have the proper thoracic extension. If you don’t have that proper thoracic extension, you can’t have scapula retraction, and it’s this whole chain of events. Chain of events that sends people down this path of sore shoulders and sore elbows.

DrMR: There are some cues for people to be able to … I’m assuming in your online course-

BP: Sure, man, it’s easy. Listen, I’ll give it all away for free, man. I do this stuff because I love it, I just love it.

DrMR: No, no, It’s fine. I mean, I appreciate someone’s put time into creating something. I just want to know where to point people. So there’s a section that helps you with scapular retraction queuing?

BP: Yep, we’ve got a whole scapula stability series. We got a whole pelvic stability series, a whole trunk stability series. Just optimize those things, and the scapula is often or always the limiting factor in building your upper body, all body parts. Your ability to stabilize and control scapular movement. And your pelvis is the same for the lower body. If you have a hard time building your quads, your glutes your hamstrings, then your ability to contract those muscles is governed by pelvic stability.

DrMR: Is that part of your on-ramp? I’m trying to make sure that people who are listening to this, if they head over to your site, and please give us the URL also. I want to make sure they jump in at the right point. So what’s the URL, and then how would you say for someone new? Where’d they start, and how would they phase in?

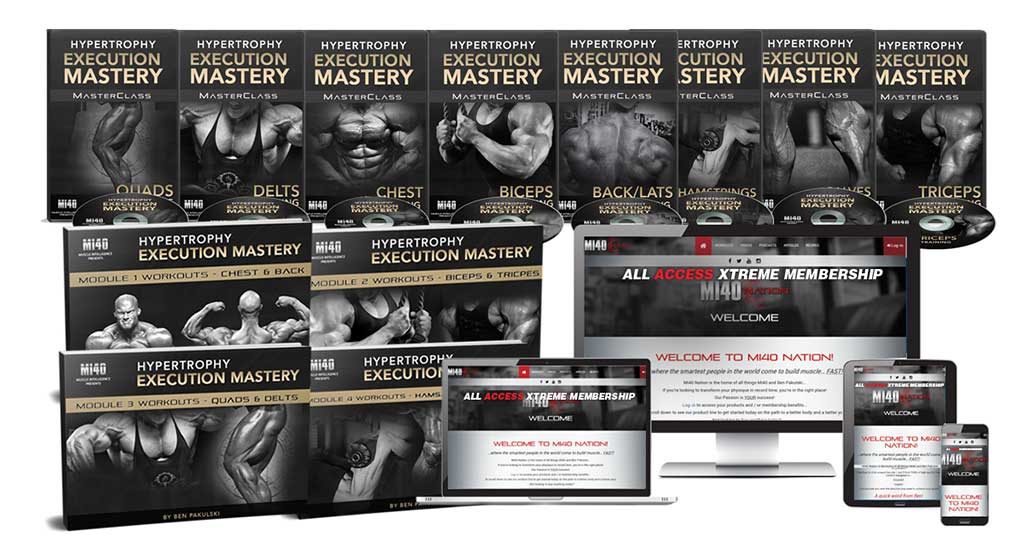

BP: Yeah, so the program I put together is called Hypertrophy Mastery. Hypertrophy is muscle-building mastery. So it’s hypertrophymastery.com. All this stuff comes with it. The primer programs are included. We build the modules, so four modules. Actually, five modules and just expanded it.

DrMR: And there’s a natural progression?

BP: Yep, each module is a different body part, and it all comes with it, man. So the scapula stability series, the pelvic stability series. Understanding all the videos around how to develop your own primer. You know, how to start. What to do when you’re done. Just try to keep it as turnkey as possible, so we can walk in no matter what level they’re at and get a great response. If someone’s more advanced, then subsequent to the Hypertrophy Mastery program, we have other more advanced programs that are tailored to specific goals.

But this is the foundational program that I created that really no matter where you are, it’s going to teach you how to master exercise for your body. So whether you are a 70-year-old lady who just wants to run and exercise, which we actually have surprisingly large numbers of those ladies, to 21-year-old boy or man trying to maximize muscle building. It’s just understanding how your body works, understanding mechanics because we all have probably the same with different length levers, different size bodies. But ultimately, muscles are muscle. It typically has the same origin insertion, and if you learn to understand those things, you can learn how to challenge it in the most effective way possible. Mechanics is very simple.

DrMR: What I like about this is you sometimes hear certain coaches point out some of these same areas of imbalances. But it seems like their solutions are so esoteric, and it’s the same thing that irritates me in the gut space where the solution is made to be way more complicated than it actually has to be. If you really understand the topic well enough, you understand, hey, a lot of this boils down to a core set of fundamentals, I guess is your five pillars. So I really appreciate that. For a module, how much time would someone roughly expect?

BP: It’s honestly not a lot. But what I suggest to people is I’ve kind of framed it so that there are about 20 videos per module. So you got 30 days to watch 20 videos. I just watched one video a day. Keep it really simple, man. Everyone has time to watch one, three to four-minute video a day.

DrMR: So they’re short videos?

BP: Yeah, I try to keep them really condensed. I try to minimize my amount of talking, and some of them are seven minutes or something.

DrMR: So maybe like 15 minutes a day would you say to watch a video, play around with some of the stuff, recommend?

BP: Yeah, and I usually suggest like right before you go to the gym, watch that video and then go try it because you don’t need to learn every exercise today. You need to learn one today, and that’s the biggest mistake people make. I’ve touched on this briefly is people try to do too many exercises. They’re never good at any of them. If you want to build your chest … How many exercises you need, Mike? The answer is one. One that fits. If you do six exercises that you suck at all of them, what good is that, right? I want to try to find one, and let’s get really good at it. Let’s master it. Then once you’ve mastered that, then we’ll introduce another one.

So that’s the biggest mistake people make is trying to do too many things because none of them really work. So they’re like, “I need to do more.” No, you don’t. You need to do less. You need to get really, really good at something, right? If you want to learn how to throw a baseball, learn how to throw a baseball. You don’t need to learn how to throw a curveball and a slider and a changeup yet. Just learn how to throw a fastball. Let’s just go in there do this one exercise and let’s master it.

Let’s do eight sets of it today, and let’s make sure your body just gets it so you have the right stability whether you’re talking chest, or it’s stability at your scapula. If you’re talking lower body or it’s stability at your pelvis. It may take you four to six weeks of just one exercise, which is why I bring down that framing of just four or five exercises per body part because you have to limit people. People just get so caught up in like, “Oh, I got to do more.” More is not better, better is better.

DrMR: No, I’m actually interested to try it because I’m sure everyone listening to this is saying, “Oh, maybe my scapula isn’t as retracted. Maybe my hamstrings could be a little bit stronger. So I think I’m going to actually go through this myself.” I like the way you break it down. I mean, 15 minutes a day isn’t daunting. It’s something that seems totally feasible.

BP: Yeah, and man, I think it’s so much more simple than people make it up to be. You understand that people don’t understand things tend to make them very convoluted because they don’t understand that well, right?

I’ve had this amazing opportunity to spend the last 20 years being one of the best bodybuilders in the world and not being very good at it. So I had to work hard. I had to learn a lot. I had to minimize the number of mistakes I’ve made. I wasn’t genetically blessed. So it was my blessing and a curse at the same time. The curse when you’re doing it, and you’re in it, you’re like, “God, this sucks,” but you’re looking back, and you’re like, “I’m so grateful for it because, without it, I wouldn’t be the man that I am.”

DrMR: Nope. I know one amoeba that was in my gut many years ago that was very similar teacher for me. It sucked at the time, but then it really was a tremendous gift in the end. Ben, as we come to a close, anything that you want to offer people in terms of final thoughts? And also, would you please let us know the URL one more time?

Episode Wrap Up

BP: Sure, it’s hypertrophymastery.com, and that’s kind of a long word for some people to know what it is. But if they’ll figure it out. Hypertrophymastery.com.

Other words? Yeah, use exercise as an opportunity to connect with your body. So many of us are so disconnected from our body we’re stuck on her head, and exercise should be this amazing ability or this amazing opportunity to connect with your muscles, connect with your body, connect with your feelings, and it shouldn’t be mindless slinging of weights. It shouldn’t be really loud death metal music. Well, that’s sometimes cool too. It should be an opportunity to contract and connect and feel and learn how to challenge muscles, and that’s how you’re going to learn how to build a great body.

It almost becomes meditative. I go to the gym. I’ve got usually headphones on with no music, or if I do, it’s something very melodic with no vocals and just really trying to get in tune and in touch with my body. Similar to the way you do when you meditate, you’re going, and you’re sitting down, and you’re trying to allow your whole body to relax. Well, some of the greatest meditation coaches that I’ve ever encountered suggest that in order to experience complete peace, you must experience complete chaos.

It’s the same idea with muscles, right? If you want to learn how to relax your muscles completely, you must first learn to contract them completely, and I think it’s a really great opportunity for anybody out there living with stress and anxiety and high amounts of tension to get in there and aggressively contract muscles. It doesn’t necessarily mean lift a tremendous amount of weight. You can, but aggressively contract muscles, and those muscles will relax. Those muscles will improve their ability to deliver nutrients.

Exercise is such a beautiful thing if you make it. It doesn’t have to be a stress. You can make it something you love. Find the things you’re good at, do more of them. Find things you’re not so good, don’t put any pressure on yourself. Do them often, do them well, but it doesn’t have to be hard. It just has to be done well first, because eventually, once you develop that skill set, you’ll be good at it. You’ll like it, right?

Like anything, nobody likes what they’re not good at. So, that’s kind of the best advice I have, man. See exercise as an opportunity for challenging, for connecting with your body, and eventually, you’re going to love it.

DrMR: Awesome. That’s a great message, man. I’m looking forward to personally checking out your programs.

BP: Thanks, man.

DrMR: Thanks for all your hard work, and thanks for coming on the show.

BP: Appreciate it, man.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!