PMS Fatigue: What It Is, Causes, and How To Treat It

Tackling Low Energy Levels Brought on by PMS

- PMS Explained|

- PMS Fatigue|

- Treatment Options|

- Reduce Stress|

- Heal Gut|

- Herbal Remedies|

- Troubleshooting|

- Recommended Products|

Fatigue is among the more than 150 physical, behavioral, or psychological symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, or PMS. PMS and PMS fatigue are often signs that the hormones responsible for women’s menstrual cycles are imbalanced.

The two most common underlying factors that can lead to hormonal imbalances in women are stress and poor gut health. The great news is that we can do something about both of these. Taking simple steps to reduce stress and improve digestion may be the ticket to less fatigue and fewer symptoms overall in the week or two before your period.

First, let’s unravel PMS and the fatigue that often comes with it.

What Is PMS?

Premenstrual syndrome describes the collection of symptoms that many women experience between ovulation and menstruation.

Globally, about half of all women of reproductive age experience PMS [1]. About 20% of those women have symptoms that disrupt their daily activities [1]. Furthermore, around 2.5-3% of women with PMS have a severe form called premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or PMDD [2].

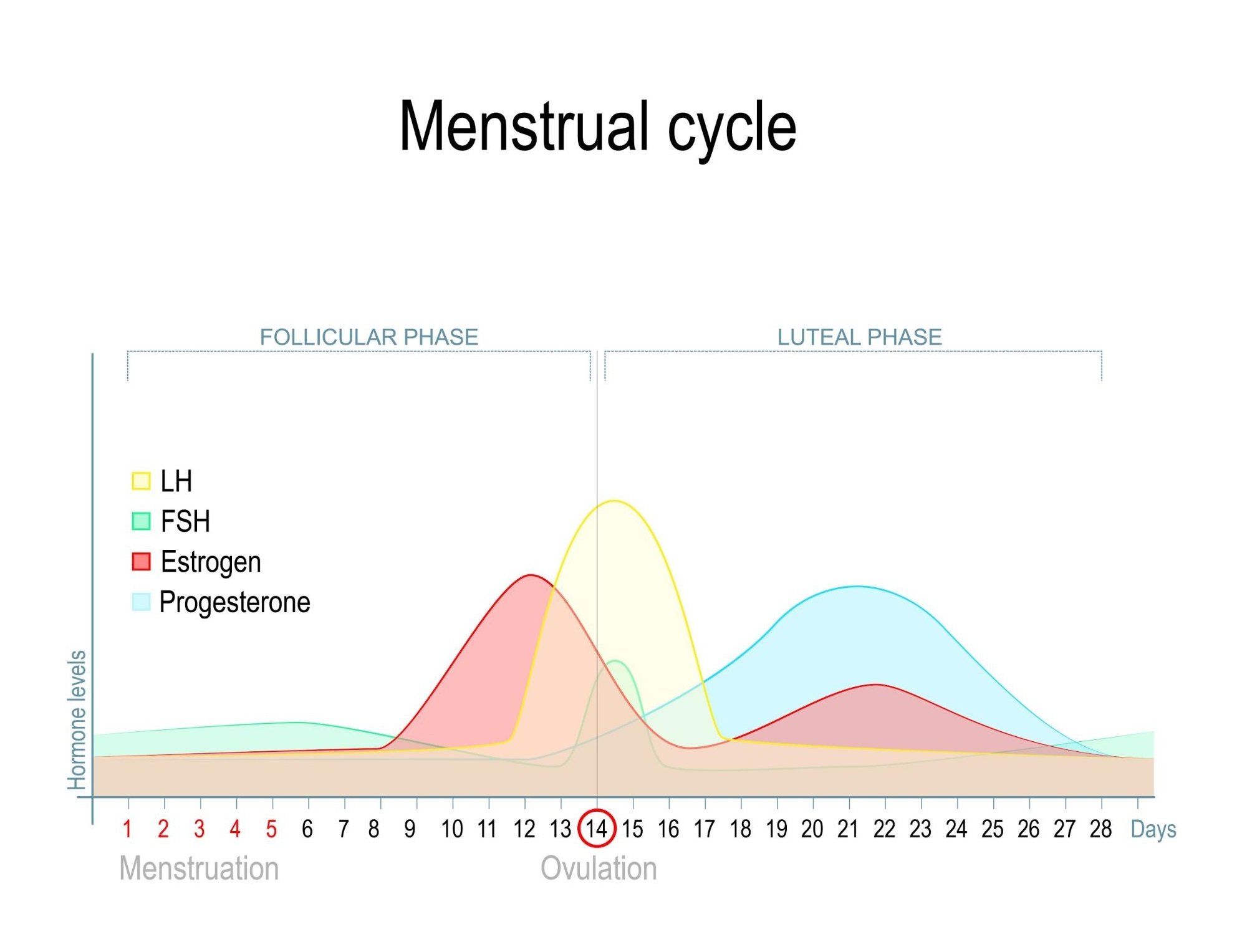

How Does the Menstrual Cycle Work?

If you’re interested in understanding the hormonal shifts that take place during the menstrual cycle, here’s a simple overview.

Follicular Phase (First Half of Cycle)

At the start of menstruation (your period), these four hormones are low:

- Estrogen

- Progesterone

- Luteinizing hormone (LH)

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

A few days after your period ends, Estrogen levels start to rise, peaking a couple of days before ovulation.

Ovulation (Mid-Cycle)

The peak in estrogen causes both LH and FSH levels to surge. This triggers the ovary to release an egg (ovulation). This is the stage where conception can happen.

Luteal Phase (Last Half of Cycle)

If the egg is not fertilized by sperm at ovulation, LH levels drop. Progesterone and estrogen levels decrease in the late part of the luteal phase. This triggers the endometrium (inner layer of the uterus that would provide nutrients to a fertilized egg) to slough off and results in menstrual blood loss, or menstruation.

PMS symptoms occur in the final days of the luteal phase, as hormone levels drop.

Symptoms of PMS

The most common PMS symptoms include the following [3]:

Physical symptoms:

- Appetite changes and food cravings

- Water retention (overall bloating) and weight gain

- Abdominal pain

- Muscular aches and pains, especially in the lower back

- Headache

- Breast tenderness and swelling

- Nausea

- Constipation

- Fatigue

Emotional symptoms:

- Restlessness and poor concentration

- Insomnia

- Mood swings and heightened emotions

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Depressed mood

What Causes PMS?

The exact causes of PMS are not clear, but it may develop as a result of imbalanced hormone levels [4, 5, 6], poor diet [5, 6], and certain genetic predispositions [7, 8, 5, 6]. Some women may also be more sensitive to normal fluctuations of estrogen and progesterone and are therefore more likely to experience PMS [6, 9]. Alcohol use [10] and cigarette smoking [6] may increase the risk of developing PMS.

Stress and poor gut health can trigger hormone imbalances, leading to symptoms of PMS. Thankfully, there’s much you can do to reduce stress, improve gut health, and resolve your PMS symptoms, including PMS fatigue.

What Causes PMS Fatigue?

One likely cause of fatigue in the days leading up to your period is the low level of estrogen. This hormonal change causes a drop in several neurotransmitters (the body’s chemical messengers) that are important for preventing insomnia, fatigue, and depression [4].

One of those neurotransmitters is serotonin, your happy-mood chemical that comes from a dietary amino acid called tryptophan. Tryptophan is abundant in protein-rich foods such as chicken, fish, and milk. When all is well in your gut, tryptophan from food gets converted into serotonin, which lifts your mood and energy levels.

However, when too much stress and a poor diet cause gut inflammation, the tryptophan that comes with your food gets converted to inflammatory proteins instead of serotonin, robbing your brain of happy chemicals [11, 12].

In a nutshell, if low estrogen levels before your period reduce your serotonin and you’re dealing with gut inflammation from stress and poor diet, you won’t have enough serotonin to give you the positive outlook and energy you had before ovulation, when your estrogen was high. In other words, you’ll find yourself saddled with PMS fatigue.

However, as mentioned before, there is much you can do to reduce or eliminate PMS symptoms, including fatigue.

How To Relieve PMS and PMS Fatigue

Many studies and my clinical experiences have shown that simple lifestyle changes, such as practicing stress-relieving techniques and improving your diet, can go a long way in improving PMS symptoms. For those who need a little more help, adding specific nutrients or herbs can tip the scales toward PMS freedom.

Let’s explore a three-pronged approach to overcoming PMS by reducing stress, improving gut health, and balancing hormones.

Reduce Stress

The following activities can go a long way toward reducing your PMS symptoms and premenstrual fatigue:

- Moderate exercise to relieve PMS-related pain, constipation, breast tenderness, anxiety, and anger [13, 5]

- Identifying stressful events and doing your best to avoid them, particularly in the two weeks leading up to menstruation

- Meditation and breathing practices that calm your nervous system [14]

- Spending time in nature to improve your mood [15]

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) focused on PMS symptoms [16, 17] (many CBT practitioners conduct online therapy sessions)

Improve Gut Health

What you eat and the composition of your gut microbiome (the community of microorganisms that regulates your digestive health and immune system) impacts your blood sugar, levels of inflammation, and hormonal balance. Here are two ways to improve your gut health:

- Make dietary changes to replace processed foods with healthy, whole foods. The Paleo Diet [18, 19, 20, 21] is a good choice for stabilizing blood sugar and supporting a healthy gut microbiome.

- Probiotics are the cornerstone of improving gut health, with the power to correct imbalances in the gut microbiome and reduce inflammation that may undermine your hormones. The most effective approach to using probiotics is to use one quality probiotic from each of these categories [22, 23]: 1) a blend of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria; 2) Saccharomyces boulardii (a beneficial yeast); and 3) a soil-based probiotic.

Balance Hormones

Certain nutrients and herbs can be very helpful in nudging your hormones back into balance. Keep in mind that supplements are most effective when used together with a healthy diet and lifestyle changes.

- Research suggests that certain herbs can be helpful for PMS symptoms [24]. Chasteberry, also called vitex, is well-studied and has been shown to be effective for PMS and PMDD in several clinical trials [25]. One meta-analysis (highest quality of research evidence) found that women who took vitex were 2.57 times more likely to stop having PMS symptoms [26] when compared to controls.

- Women with low dietary intake of the B vitamins thiamine (B1) and riboflavin (B2) may be more susceptible to PMS symptoms [27]. Eating higher amounts of whole grains, meat, and fish could reduce the risk of developing PMS by 35% [28]. Another B vitamin found to help with PMS is vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) [29], but supplements containing only B6 may be less effective than multivitamins containing all B vitamins at reducing PMS symptoms [30].

- Vitamin D levels are sometimes low in women with PMS and may contribute to symptoms [31]. A moderate daily dose of sunlight or a vitamin D supplement (balanced with vitamin K2) can reduce PMS symptoms in some women [32].

- Calcium levels may also be low in women with worse PMS symptoms. Calcium supplements or high-calcium foods, such as dairy products or canned salmon [33], can raise calcium levels and reduce PMS symptoms [31].

- Magnesium levels are not necessarily low in women with PMS [34], but some evidence suggests that magnesium supplements may help treat PMS-related anxiety [35].

Your Plan for Relieving PMS Fatigue

In summary, your plan for relieving PMS fatigue and other symptoms should include stress reduction, dietary changes, and a simple supplement protocol:

- High-quality probiotic supplements to help restore gut health

- A high-quality herbal formula to help balance hormones

- A multi-vitamin formula that contains B vitamins, vitamin D, calcium and magnesium

Anyone struggling with PMS fatigue probably knows it can feel impossible to make changes to daily life when you’re exhausted. So, I recommend using the days during your cycle when your energy levels are higher to start implementing your PMS relief plan. For many women, energy levels are highest the week or so after their period ends.

Ideally, you’ll start to see improvements in your PMS symptoms within the first few menstrual cycles.

What To Do If PMS Persists

If you have intense PMS or PMDD (the most severe form of PMS) that doesn’t resolve after making diet and lifestyle changes, consider reaching out for professional support from a healthcare provider. Options include:

- A gynecologist who can diagnose more complex gynecological conditions that may contribute to your symptoms

- A functional health practitioner who can help with additional treatment options to improve gut health and balance hormones

- A health coach who can help you to stay on track with dietary and lifestyle changes

Life Is Better Without PMS

PMS symptoms are disruptive and can be debilitating. However, there’s much you can do to prevent monthly episodes of PMS fatigue, mood swings, and other troublesome symptoms.

I have observed in my clinic that most women can significantly reduce symptoms of PMS within one or two cycles. Reduce your stress levels, improve your diet, and take a few key supplements, and you’ll be on your way to living PMS-free.

Dr. Michael Ruscio is a DC, natural health provider, researcher, and clinician. He serves as an Adjunct Professor at the University of Bridgeport and has published numerous papers in scientific journals as well as the book Healthy Gut, Healthy You. He also founded the Ruscio Institute of Functional Health, where he helps patients with a wide range of GI conditions and serves as the Head of Research.➕ References

- A DM, K S, A D, Sattar K. Epidemiology of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Feb;8(2):106-9. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8024.4021. Epub 2014 Feb 3. Erratum in: J Clin Diagn Res. 2015 Jul;9(7):ZZ05. PMID: 24701496; PMCID: PMC3972521.

- Fatemi M, Allahdadian M, Bahadorani M. Comparison of serum level of some trace elements and vitamin D between patients with premenstrual syndrome and normal controls: A cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2019 Sep 22;17(9):647-652. doi: 10.18502/ijrm.v17i9.5100. PMID: 31646259; PMCID: PMC6804325.

- Bu L, Lai Y, Deng Y, Xiong C, Li F, Li L, Suzuki K, Ma S, Liu C. Negative Mood Is Associated with Diet and Dietary Antioxidants in University Students During the Menstrual Cycle: A Cross-Sectional Study from Guangzhou, China. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019 Dec 26;9(1):23. doi: 10.3390/antiox9010023. PMID: 31888014; PMCID: PMC7023165.

- Vaghela N, Mishra D, Sheth M, Dani VB. To compare the effects of aerobic exercise and yoga on Premenstrual syndrome. J Educ Health Promot. 2019 Oct 24;8:199. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_50_19. PMID: 31867375; PMCID: PMC6852652.

- Chiaramonte D, Ring M, Locke AB. Integrative Women’s Health. Med Clin North Am. 2017 Sep;101(5):955-975. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.04.010. Epub 2017 Jul 14. PMID: 28802473.

- Dhingra V, Magnay JL, O’Brien PM, Chapman G, Fryer AA, Ismail KM. Serotonin receptor 1A C(-1019)G polymorphism associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Oct;110(4):788-92. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000284448.73490.ac. PMID: 17906010.

- Huo L, Straub RE, Roca C, Schmidt PJ, Shi K, Vakkalanka R, Weinberger DR, Rubinow DR. Risk for premenstrual dysphoric disorder is associated with genetic variation in ESR1, the estrogen receptor alpha gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 Oct 15;62(8):925-33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.019. Epub 2007 Jun 27. PMID: 17599809; PMCID: PMC2762203.

- Halbreich U. The etiology, biology, and evolving pathology of premenstrual syndromes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003 Aug;28 Suppl 3:55-99. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00097-0. PMID: 12892990.

- Fernández MDM, Saulyte J, Inskip HM, Takkouche B. Premenstrual syndrome and alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 16;8(3):e019490. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019490. PMID: 29661913; PMCID: PMC5905748.

- M. P. HEYES, K. SAITO, J. S. CROWLEY, L. E. DAVIS, M. A. DEMITRACK, M. DER, L. A. DILLING, J. ELIA, M. J. P. KRUESI, A. LACKNER, S. A. LARSEN, K. LEE, H. L. LEONARD, S. P. MARKEY, A. MARTIN, S. MILSTEIN, M. M. MOURADIAN, M. R. PRANZATELLI, B. J. QUEARRY, A. SALAZAR, M. SMITH, S. E. STRAUSS, T. SUNDERLAND, S. W. SWEDO, W. W. TOURTELLOTTE, QUINOLINIC ACID AND KYNURENINE PATHWAY METABOLISM IN INFLAMMATORY AND NON-INFLAMMATORY NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE, Brain, Volume 115, Issue 5, October 1992, Pages 1249–1273, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/115.5.1249

- Maes I, Mihaylova V, Ruyter A, Kubera A, Bosmans U, The immune effects of TRYCATs (tryptophan catabolites along the IDO pathway): relevance for depression – and other conditions characterized by tryptophan depletion induced by inflammation. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2007 Dec; 28(6): 826-831

- Yesildere Saglam H, Orsal O. Effect of exercise on premenstrual symptoms: A systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2020 Jan;48:102272. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102272. Epub 2019 Nov 27. PMID: 31987230.

- Gerbarg PL, Jacob VE, Stevens L, Bosworth BP, Chabouni F, DeFilippis EM, Warren R, Trivellas M, Patel PV, Webb CD, Harbus MD, Christos PJ, Brown RP, Scherl EJ. The Effect of Breathing, Movement, and Meditation on Psychological and Physical Symptoms and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2886-96. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000568. PMID: 26426148.

- Bratman GN, Hamilton JP, Hahn KS, Daily GC, Gross JJ. Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Jul 14;112(28):8567-72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510459112. Epub 2015 Jun 29. PMID: 26124129; PMCID: PMC4507237.

- Kancheva Landolt N, Ivanov K. Short report: cognitive behavioral therapy – a primary mode for premenstrual syndrome management: systematic literature review. Psychol Health Med. 2020 Aug 26:1-12. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1810718. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32845159.

- Lustyk MK, Gerrish WG, Shaver S, Keys SL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009 Apr;12(2):85-96. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0052-y. Epub 2009 Feb 27. PMID: 19247573.

- Whalen KA, McCullough ML, Flanders WD, Hartman TJ, Judd S, Bostick RM. Paleolithic and Mediterranean Diet Pattern Scores Are Inversely Associated with Biomarkers of Inflammation and Oxidative Balance in Adults. J Nutr. 2016 Jun;146(6):1217-26. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.224048. Epub 2016 Apr 20. PMID: 27099230; PMCID: PMC4877627.

- Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutr J. 2014 Jan 16;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-5. PMID: 24428901; PMCID: PMC3896778.

- Masharani U, Sherchan P, Schloetter M, Stratford S, Xiao A, Sebastian A, Nolte Kennedy M, Frassetto L. Metabolic and physiologic effects from consuming a hunter-gatherer (Paleolithic)-type diet in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015 Aug;69(8):944-8. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.39. Epub 2015 Apr 1. PMID: 25828624.

- Jönsson T, Granfeldt Y, Ahrén B, Branell UC, Pålsson G, Hansson A, Söderström M, Lindeberg S. Beneficial effects of a Paleolithic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a randomized cross-over pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009 Jul 16;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-35. PMID: 19604407; PMCID: PMC2724493.

- American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ, Quigley EM. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104 Suppl 1:S1-35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. PMID: 19521341.

- Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct;109(10):1547-61; quiz 1546, 1562. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.202. Epub 2014 Jul 29. PMID: 25070051.

- Maleki-Saghooni N, Karimi FZ, Behboodi Moghadam Z, Mirzaii Najmabadi K. The effectiveness and safety of Iranian herbal medicines for treatment of premenstrual syndrome: A systematic review. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2018 Mar-Apr;8(2):96-113. PMID: 29632841; PMCID: PMC5885324.

- Cerqueira RO, Frey BN, Leclerc E, Brietzke E. Vitex agnus castus for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017 Dec;20(6):713-719. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0791-0. Epub 2017 Oct 23. PMID: 29063202.

- Csupor D, Lantos T, Hegyi P, Benkő R, Viola R, Gyöngyi Z, Csécsei P, Tóth B, Vasas A, Márta K, Rostás I, Szentesi A, Matuz M. Vitex agnus-castus in premenstrual syndrome: A meta-analysis of double-blind randomised controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2019 Dec;47:102190. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.08.024. Epub 2019 Aug 30. PMID: 31780016.

- Patricia O Chocano-Bedoya, JoAnn E Manson, Susan E Hankinson, Walter C Willett, Susan R Johnson, Lisa Chasan-Taber, Alayne G Ronnenberg, Carol Bigelow, Elizabeth R Bertone-Johnson, Dietary B vitamin intake and incident premenstrual syndrome, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 93, Issue 5, May 2011, Pages 1080–1086, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.009530

- https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Thiamin-HealthProfessional/

- Efficacy of vitamin B-6 in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome:systematic review

- Retallick-Brown H, Blampied N, Rucklidge JJ. A Pilot Randomized Treatment-Controlled Trial Comparing Vitamin B6 with Broad-Spectrum Micronutrients for Premenstrual Syndrome. J Altern Complement Med. 2020 Feb;26(2):88-97. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0305. Epub 2020 Jan 10. PMID: 31928364.

- Abdi F, Ozgoli G, Rahnemaie FS. A systematic review of the role of vitamin D and calcium in premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019 Mar;62(2):73-86. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2019.62.2.73. Epub 2019 Feb 25. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020 Mar;63(2):213. PMID: 30918875; PMCID: PMC6422848.

- Arab A, Golpour-Hamedani S, Rafie N. The Association Between Vitamin D and Premenstrual Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Current Literature. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019 Sep-Oct;38(7):648-656. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2019.1566036. Epub 2019 May 10. PMID: 31074708.

- https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/

- Moslehi M, Arab A, Shadnoush M, Hajianfar H. The Association Between Serum Magnesium and Premenstrual Syndrome: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019 Dec;192(2):145-152. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01672-z. Epub 2019 Mar 18. PMID: 30880352.

- Boyle NB, Lawton C, Dye L. The Effects of Magnesium Supplementation on Subjective Anxiety and Stress-A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2017 Apr 26;9(5):429. doi: 10.3390/nu9050429. PMID: 28445426; PMCID: PMC5452159.

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!