Practitioner Research Review – December 2019

Dr. Michael Ruscio’s Monthly – Future of Functional Medicine Review Clinical Newsletter

Practical Solutions for Practitioners

In Today’s Issue

Research

- Mood Disorders and Gluten: It’s Not All in Your Mind! A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

- Is SIBO A Real Condition?

- Production and Use of Hymenolepis diminuta Cysticercoids as Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutics.

- Rapid-Fire Research – Ultra-concise summaries of noteworthy studies

- Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with probiotics. An etiopathogenic approach at last?

![]()

Research

*Please note: the case study and research studies are not meant to be mutually reinforcing. There is often concept overlap, however the research studies are a collection of the most clinically meaningful research that has been published recently.

Mood Disorders and Gluten: It’s Not All in Your Mind! A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

Nutrients. 2018 Nov 8;10(11). pii: E1708. doi: 10.3390/nu10111708.

Study purpose

- Summarize data regarding mood and gluten intake.

Intervention:

- Systematic review with meta-analysis of prospective studies for effects of gluten on mood symptoms in patients with or without gluten-related disorders

- 3 randomised-controlled trials and 10 longitudinal studies comprising 1139 participants fit the inclusion criteria.

Main Results:

- A gluten-free diet (GFD) significantly improved pooled depressive symptom scores in GFD-treated patients ( p < 0.0001),

- with no difference in mean scores between patients and healthy controls after one year (p = 0.94)

- There was a tendency towards worsening symptoms for non-coeliac gluten-sensitive patients during a blinded gluten challenge vs. placebo (p = 0.25).

- But, not significant, in part due to CI over zero.

Additional Results:

- When looking at the best quality data, the association between gluten and the altered mood was attenuated. Key point: be tempered in your enthusiasm regarding a hypothesis, if the hypothesis’s support is weakened as data quality increase. Hint: The same thing applies to T4+T3 thyroid therapy.

- Two RCTs compared the mean depression scores of subjects during the gluten and placebo challenge periods and were included in meta-analysis [42, 56] (Figure 5). We found a trend towards worsened depressive symptoms during the gluten challenge period compared to placebo, although this did not reach significance.

- GF dieting appears to improve mood in those with CD, IBS, and NCGS, but not to improve mood in those with asymptomatic/silent CD.

- We found that a long-term GFD may significantly reduce and normalize the severity of depressive symptoms for subjects with CD, IBS and NCGS, with a medium-large effect for both symptomatic and atypical CD patients, but no effect for asymptomatic/silent cases [70]

Limitations:

- Knowing how massive the placebo impact is, it should be noted that some of the data from the systematic review were from non-randomized studies. Thus, a selection bias may exist in this data. Caution is therefore warranted.

- All prospective intervention studies—randomised, non-randomised, longitudinal—which investigated the change in the severity of mood symptoms as a primary or secondary outcome using a validated questionnaire.

- As you can see below, the majority of the data was from single-arm (non-placebo comparison) so bias in this study is likely high. 3 studies were blinded, 10 were not.

- Of the 13 studies, three were RCTs [42, 53, 56]. Study participants were subjects with self-reported NCGS with [42] and without [56] diagnosed IBS, and asymptomatic EmA-positive subjects [53]. Each of these studies excluded CD either by previous diagnosis [53] or study screening [42, 56]. The remaining 10 studies were single-arm before-after studies.

- The data for this study was poor

- Unfortunately, the overall quality of the evidence base was poor and confounding factors were problematic.

IMPORTANT:

- “Wait a second Dr. Ruscio, you are being overly critical…” Read further and the researchers support my suspicion of bias. Said simply, roughly 70% of the data here was biased.

- Of the RCTs, one study was found to have a low risk of bias and two were found to have a high risk of bias. Of the non-randomised studies, three were found to have a moderate risk of bias while the remaining seven were found to have a serious risk of bias.

- The effect of gluten on mood may have only been significant for those with classical celiac, and not for those with atypical or silent CD.

- there was a significant difference in effect between those with classical, atypical and silent CD (p = 0.003) with high heterogeneity between subgroups (I2 = 82.5%) (Figure 3B); while classical CD patients exhibited a significant effect (SMD −0.65, 95% CI −0.96 to −0.34; p < 0.0001), the effect for silent CD patients was nonsignificant (SMD −0.06, 95% CI −0.38 to 0.26; p = 0.71) and one study reported a significant effect for atypical CD patients.

- For 110 classical CD patients, there was a reduction of 31% of patients positive for depression after following a GFD (RD−0.31, 95% CI −0.52 to −0.10; p = 0.003). All the included data is for classical CD patients following a GFD for one year; no studies reported this outcome for non-CD patients.

- No data for NCGS patients.

- HOWEVER, some bias may run the other way – thus masking the clinical benefit seen from a gluten-free diet. This is based upon location bias – those studies in Finland were less likely to show clinical benefit when going gluten-free.

- Inspection from the funnel plot that arose from our main analysis (Figure 8) suggests the presence of publication bias due to location biases [68], with published studies from Finland less likely to find a large effect from a GFD on reducing depressive symptom scores relative to published studies from other countries.

- And, data looking at the benefit of GF diets in depressed cohorts is still lacking

- As we found no studies that attempted a GFD intervention on a sample of patients with depression, despite evidence for significantly higher levels of gluten-related antibodies in patients with the major depressive disorder [19], , this would be an interesting topic for future studies to address in order to help assess the directionality of the relationship between depression and gluten.

- there was a significant difference in effect between those with classical, atypical and silent CD (p = 0.003) with high heterogeneity between subgroups (I2 = 82.5%) (Figure 3B); while classical CD patients exhibited a significant effect (SMD −0.65, 95% CI −0.96 to −0.34; p < 0.0001), the effect for silent CD patients was nonsignificant (SMD −0.06, 95% CI −0.38 to 0.26; p = 0.71) and one study reported a significant effect for atypical CD patients.

Authors Conclusion:

- “Our review supports the association between mood disorders and gluten intake in susceptible individuals. The effects of a GFD on mood in subjects without gluten-related disorders should be considered in future research.”

Interesting Notes:

- “The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that 4.4% of the global population was suffering from clinical depression.”

- “A growing body of evidence suggests that mood symptoms are associated with a spectrum of gluten-related disorders [9, 11, 12]. Reports of health improvements after following a GFD in the absence of CD has led to non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) becoming increasingly recognised as its own clinical entity [13], with evidence indicating a higher prevalence than CD [14]. In contrast to CD, specific serological markers for NCGS are lacking; only some patients exhibit increased antibodies to gluten peptides and no mucosal damage is generally observed [15].”

- “More recently, mood symptoms are frequently reported as a result of wheat ingestion [17] with ‘low mood’ being a common motivation for gluten avoidance [18] in the absence of both CD and wheat allergy. Furthermore, recent clinical studies have found raised gluten-related antibodies in patients with bipolar, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia [19, 20, 21], while episodes of acute mania may be associated with increased serum levels of antibodies against gliadin [22]. Hence, there is mounting evidence for a, potentially bidirectional, relationship between gluten sensitivity and psychiatric disorders.”

- “B-vitamin supplementation was found to significantly improve depression in adults with longstanding CD on a GFD [27].”

- “Significant improvements in mood disorders and psychological well-being have been recognised in patients with CD [30, 31, 32], IBS [33] and NCGS [34] following a GFD, although the magnitude of improvement is found to be dependent on good dietary adherence [11, 35]. Moreover, anti-gliadin IgG antibodies disappeared in NCGS patients [34] and markers of systemic inflammation were reduced in IBS patients [36].”

- Gluten-free diet can reduce the quality of life, so don’t recommend strict adherence without due care.

- hypervigilance to a GFD, associated with greater knowledge, was significantly associated with reduced quality of life [44]

- A low FODMAP diet may also improve mood

Clinical Takeaways:

- A gluten-free diet MAY improve mood but data here are still lacking, of poor quality and suffer from bias.

- Therefore, clinicians should carefully and objectively explore this with their patients, being VERY careful not to impart bias on your patients.

- If your patient appears afraid of food, your conversation should outline the non-definitive nature of the research in gluten-free dieting, thus helping unbias their perspective.

- What to tell your patients:

- A gluten-free diet may improve your mood, however it may not. The data here are split. There are other gut factors that could be causing your depression. So, we will start with the diet and improving your GI health. Then work to reintroduce foods, understanding that gluten may, or may not, be a problem.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

Please be careful and objective with gluten-free diet recommendations with your patients. The data do not support the hysterical avoidance that most patients are programmed with. It is in your patient’s best interest to handle this responsibly, not dogmatically.

Is SIBO A Real Condition?

Altern Ther Health Med. 2019 Sep;25(5):30-38.

Happy to announce this is a paper I wrote and has been published in the journal Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine.

We have included the full PDF here.

Study purpose

- A balanced review of the data regarding SIBO testing, treatment, and management with the goal of establishing non-biased best practices.

Intervention:

- Non-systematic review.

Main Results:

- The results for the review fall into two categories.

- Ineffective Action:

- Treat only SIBO labs; Treat for SIBO if no symptoms are exhibited; Recommending eating or avoiding foods because they might be good or bad for SIBO; Recommending treatments that are non-validated.

- Effective Action:

- Use SIBO breath results, in addition to history and current symptoms, to determine the best treatment; Find foods that work for patients based on dietary elimination and reintroduction; Apply validated treatment for SIBO and IBS in a logical ‘step-up’ like treatment approach.

Additional Results:

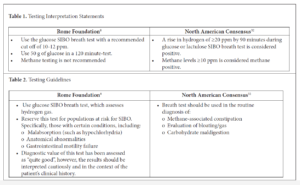

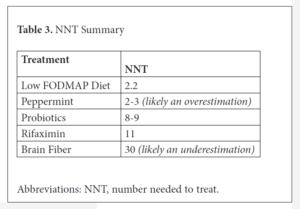

- There are a number of helpful comparison tables I recommend reviewing. I have included a couple here:

Authors Conclusion:

- Testing and treating SIBO can offer patients clinically significant relief. However, these tests and treatments must be applied with circumspection to prevent over-testing, over-treatment, squandering resources, or creating fear around certain foods.

Clinical Takeaways:

- The conclusion provides these.

- What to tell your patients:

- Warm your patients about ineffective actions. These things plague patients, either due to creating excessive testing, fear and/or dietary restrictions. Understanding the right way to address SIBO will significantly impact your patient’s wellbeing.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

For reasons I don’t understand, there seems to be a degree of zealotry regarding SIBO. It took a fair amount of time to write this paper, but I hope it will function as a credible piece of evidence (appearing in a peer-reviewed journal) for providers to consult when navigating unreviewed internet claims.

Production and Use of Hymenolepis diminuta Cysticercoids as Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutics.

J Clin Med. 2017 Oct 24;6(10). pii: E98. doi: 10.3390/jcm6100098.

Study purpose

- Attempt to better understand how to use helminth therapy.

Intervention:

- “In this study, we describe the production and use of HDCs in a manner that is based on reports from individuals self-treating with helminths, individuals producing helminths for self-treatment, and physicians monitoring patients that are self-treating.”

Main Results:

- Helminthic therapy appears effective, according to preliminary evidence.

- Based on the study design and the results, it was concluded that the generally positive effects of helminthic therapy observed in the study were probably real and not primarily due to artifacts such as survivor bias, expectations of the participants, and normalization to the mean [22, 31].

- Based on that ongoing work, which now includes more than 1000 self-treatment cases, we hypothesize that the rat tapeworm, Hymenolepis diminuta, will be an effective organism for helminthic therapy.

- The therapeutic effects and adverse side effects of self-treatment with HDCs have been described previously in two studies [22, 31]. The first study [22], by Cheng et al., described the effects of HDCs in a population of adults who had completed a survey created by the authors.

- The rat tapeworm (HDC) apparently has the following profile:

- Production is relatively straight-forward.

- The risk of adverse side effects is apparently low.

- The organisms do not leave the lumen of the gut

- The organisms generally do not survive long in humans and are not communicable via human-to-human transmission.

- The organisms appear to be generally effective in the treatment of autoimmune conditions, neuropsychiatric disorders, inflammatory conditions of the bowel, and with some caveats, allergic conditions.

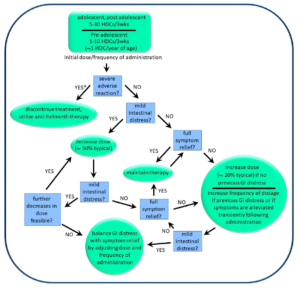

- Dosage: 5-100 HDCs dosed weekly to every 3 weeks. And usually needs to be increased over time.

- The treatment regimens used by various patients ranged from 5 HDCs every 3 weeks to 100 HDCs per week. Physicians were unable to determine indicators that might be used to predict which patients required larger doses versus those that required smaller doses. However, pediatric patients generally used lower doses than did adults.

- In general, the effective dosage during the first 6 months was gradually increased by roughly 2 to 3-fold for effective long-term maintenance (>6 years).

- Maintenance dosage: appears within the same range as Tx.

- After optimization as described above, adult patients typically used treatment regimens for long term maintenance between 10 HDCs every 3 weeks to 100 HDCs per week, while pediatric individuals typically used treatment regimens between 3 HDCs every 3 weeks to 20 HDCs every three weeks.

- Administration:

- avoid hot food/liquid and/or alcohol proximal to dosing

- avoid category 1 probiotics (lacto and bifido). boulardii appears OK. No mention of soil-based (category 3) probiotics.

- Many OTC medications appear OK; antihistamines, anti-inflammatories…

- First, the avoidance of very hot liquids or high concentrations of alcohol immediately following the administration of HDCs was recommended.

- The supplier suggested that milk-based probiotics would decrease beneficial systemic effects of the HDCs, whereas probiotics that were not milk-based would have no effect. In particular, bifidobacteria and lactobacilli were noted as being problematic, whereas Ohhira’s® probiotics and Saccharomyces boulardii were noted as being benign and, in some cases, helpful when taken with the HDCs.

- Several physicians and suppliers of HDCs reported that the helminths work well in combination with standard pharmaceutical interventions, such as over-the-counter drugs used for seasonal allergies, prescription medications for inflammatory bowel disease, and prescription medications for neuropsychiatric disorders.

- Likelihood of benefit – appears extremely likely to suffer from bias and may predominantly apply for pediatric autism cases.

- approximately 50% of individuals with inflammatory-related illness benefited from exposure to HDCs. However, approximately 95% of these reports were derived from self-treatment by the pediatric population, and most of these individuals had autism spectrum disorders with associated inflammation. Therefore, the available information is skewed to this population.

- Consideration for treatment and caveats

- As might be expected, the reported effectiveness of HDCs depended on the purpose of the therapy.

- Conditions effectively treated included various anxiety disorders and other neuropsychiatric disorders, including migraine headaches, Tourette’s syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, and major depressive disorder. Autoimmune conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease, were apparently also treated effectively.

- Mixed results were obtained treating allergies and arthritis, and a very limited number of reports suggested that self-treatment with HDCs may treat lupus, Hashimoto’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, but not Alzheimer’s disease. Some self-treaters noted an improvement or even a resolution of conditions that were not their reason for self-treatment. These included hemorrhoids (resolved), cardiac arrhythmias (resolved), and varicose veins (some improvement).

- Adverse events

- Of the 707 total cases evaluated, several adverse effects of self-treatment were noted, all in the pediatric population. Most pediatric individuals with autism experienced a slight but transient increase in hyperactivity following self-treatment.

Additional Results:

- “It was not until 2005 that the first clinical trials were published showing that apparently benign helminths could alleviate inflammatory bowel disease in humans [10, 11]. Those studies were followed closely by work showing that accidental colonization with helminths halts the progression of the most common form of multiple sclerosis [12, 13].”

Limitations:

- Overall the research here is still very early

Authors Conclusion:

- “Helminths have a largely unexplored potential to treat a wide range of inflammation-related diseases [3] and may prove very effective at treating some dread diseases that have proven extremely resistant to pharmaceutical-based approaches.

- “At the same time, based on sociomedical studies [22, 31], as well as some clinical trials [10, 35], some conditions are likely to prove resistant, and not all individuals will respond well. Supporting this view, studies in animal models demonstrate that, although helminths do help regulate immune function, they do not effectively treat all inflammatory diseases, and in some cases make certain pre-existing conditions worse, and they may not affect many diseases that are a “hard-wired” result of genetic mutation [36, 37, 38, 39].”

Interesting Notes:

- “Helminthic therapy, the use of helminths to treat disease, offers the best hope of decreasing inflammation via immunomodulation rather than immunosuppression [1, 2, 3], and probably also improves mucosal barrier function [4]. “

- “The scientific foundation behind this hope is based on the long co-evolutionary history of helminths with their vertebrate hosts [5]. Forces driving that coevolution include advantages to both host and helminth in minimizing the impact of helminth colonization on host fitness [6, 7]. This evolutionary process has resulted in the existence of helminths, which are benign under conditions of adequate nutrition, but yet modulate host immune function in a manner that decreases inflammation without impairing immune function [1, 7, 8].”

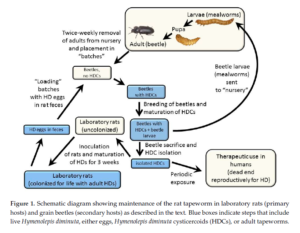

- Production cycle

Clinical Takeaways:

- Helminth may offer benefit from inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. However, the data here are early, likely to suffer from large bias and in a specific population (pediatric autism).

- What to tell your patients:

- This could be a therapy to consider, but only after exhausting all other treatments. We should also be cautious because there is still not yet good data to support this therapy.

Dr. Ruscio Comments

I advise patients to consider FMT before helminthic therapy. I have not been impressed with the handful of patients who have elected to self-administer helminths. The note about bias and a specific treatment cohort is very important to consider.

Rapid-Fire Research: Ultra-Concise Summaries of Noteworthy Studies

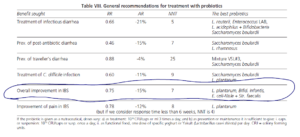

Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with probiotics. An etiopathogenic approach at last?

Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009 Aug;101(8):553-64.

- “A thorough meta-analysis of 20 RCTs (1,404 subjects) shows that the use of probiotics was associated with overall improvement in IBS (RR = 0.77) and a reduction in abdominal pain episodes (RR = 0.78) (70).”

- R’s Note: Why gastroenterologist handwave when asked about probiotics is beyond me….

- Sample sizes in these studies are often small however, this is a valid criticism.

- Even when consolidating to quality RCTs only, probiotics still show benefit in IBS…

- Similar conclusions were reached in a meta-analysis that identified 19 quality RTCs published between 1966 and 2008 (71), including the three with Lp299v mentioned above. Both claim that probiotics are beneficial in the treatment of IBS, but the extent of the benefit and the most effective species (or combinations) are still somewhat uncertain.

- Similar conclusions were reached in a meta-analysis that identified 19 quality RTCs published between 1966 and 2008 (71), including the three with Lp299v mentioned above. Both claim that probiotics are beneficial in the treatment of IBS, but the extent of the benefit and the most effective species (or combinations) are still somewhat uncertain.

- IBS is the most common functional digestive disorder and may affect 11-20% of the adult population in industrialized countries.

- Probiotic Mechanism of Action

- Promotion of phagocytosis (first line of defense) with:

- Increase in INFγ secretion

- Greater expression of complement receptors in phagocytes

- Inhibition of pathogenic bacterial growth due to the production of bacteriocins or defensins

- Local modulation of the immune system, cellular (lymphocytes) and humoral (IgA and IgG)

- Changes in the volume and composition of stools and intraluminal gas:

- More formed in diarrhea-predominant IBS (especially with Lactobacilli); less compact in constipation-predominant IBS (especially with Bifidobacteria)

- Less abdominal bloating or distension

- Greater ability to deconjugate bile salts, with the absorption of the resulting products, by Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacteria spp. → reduction in cholerrheic diarrhea

- The phenomenon of competitive inhibition against pathogenic bacteria

- Suppression of local inflammatory response by reducing TNFα secretion

- Anti-inflammatory effect on the intestinal mucosa, which produces deactivation of the imbalance in intramucosal serotonin production, which causes:

- Reduction in anomalous activation of intestinal motility → less diarrhea and abdominal distension

- Reduction in visceral hypersensitivity → less abdominal pain

- Probiotic Benefits

- Regulation of the intraluminal environment:

- Fermentation of non-degradable dietary fiber and intraluminal mucoproteins

- Regulation of the planktonic intestinal microflora, anti-pathogen barrier (Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli, Campylobacter)

- Favors lactose digestion

- Modulation of intraluminal gas production, reducing the bacteria that produce it ( coli, Veillonella) and increasing the bacteria that do not (Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria)

- Adjustment of the immune and inflammatory response:

- Cellular: B and T lymphocytes

- Humoral: secretion of immunoglobulins A and G

- Increase in trophic responses:

- Control of epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation

- Maintenance of the normal growth of new cells in intestinal mucosa crypts → prevents atrophy of villi

- Regulation of intestinal motility (fasting and postprandial):

- Improvement of colonic transit through the production of short-chain fatty acids (acetic, propionic, butyric) → intraluminal acidification

- Modulation of the motor response to intraluminal distension.

I’d like to hear your thoughts or questions regarding any of the above information. Please leave comments or questions below – it might become our next practitioner question of the month.

Like what you’re reading?

Please share this with a colleague and help us improve functional medicine

Discussion

I care about answering your questions and sharing my knowledge with you. Leave a comment or connect with me on social media asking any health question you may have and I just might incorporate it into our next listener questions podcast episode just for you!